The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui at Portland’s not-for-profit Twilight Theater would have pleased Bertolt Brecht enormously. As Producing Artistic Director Dorinda Toner explained to me, anyone – amateur or professional – can audition for roles or submit proposals for plays to this community theater in North Portland’s Kenton neighborhood. Because professional actors sometimes perform here, it is not strictly the kind of amateur theater Brecht worked with and praised in Scandinavian exile when he wrote the play in 1941, but it has the flavor he admired. The theater is small and intimate, seating only 84 plus accessibility seating. Many of the actors in its productions hold full-time day jobs and have not been professionally trained. Producing Arturo Ui is an ambitious task for any theater, yet it was for its unmistakably timely theme that Toner selected Tobias Andersen and Michael Streeter’s proposal to direct Brecht’s parable of Hitler’s rise to power.

Drawing from their combined, extensive directorial and acting experience, Andersen and Streeter took on this gargantuan task with fourteen actors and a musician and brought together a dazzling show amid the most challenging of circumstances. In December, a car crashed into the building under the theater and started a fire, leading to some smoke damage and a power outage, so that rehearsals had to move to a different location for a week. Added to these woes were about five cases of Covid, even forcing one actor to leave the production. Two other actors dropped out due to deaths in their families. And in January, two back-to-back ice storms halted rehearsals except for a few zoom meetings. Typically, Toner told me, there are four to five weeks of rehearsals with an additional week of tech, but this time there was only one tech rehearsal, and the show opened a day late due to the ice storms. And surprisingly, stage manager Ian Leiner deftly took over three roles when I saw the play – the announcer, the actor, and Hook – after one day’s notice. I only learned after the show that two tap dances (Alyssa Beckman) had to be cut between scenes.

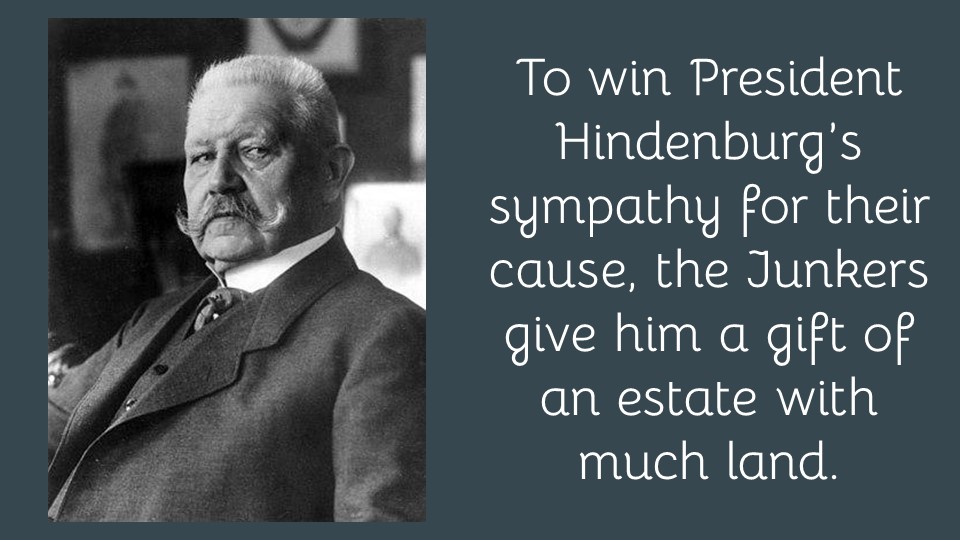

How could this production have turned out so well? It’s not a mystery. Bouncing back from situations like this requires meticulous planning and talent. The elements of Brecht’s epic theater had been thoroughly conceived and designed. Exceptional talent was in place. And as for planning, spectators encountered Brechtian theater even before entering the seating area as they passed by a group of signs with the main plot points worded like newspaper headlines: “New developments in the dock subsidy scandal…” / “The true facts about Dogsborough’s will and confession…” / “Sensation at warehouse fire trial…” / “Ignatius Dullfeet blackmailed and murdered…” / “Friends murder gangster Ernesto Roma… ” / “Cicero taken over by gangsters…”

(Signs at entrance to seating. Photos by Setje-Eilers.)

In the moments before the show, the audience members can study the stunning set: two chairs tilting on uneven legs and a large cityscape backdrop of Chicago in the style of German Expressionism with slanted skyscrapers and the two towers of the Wrigley Building leaning precariously (set design: Michael Streeter; scenic painter & artwork: Laura Streeter). Ui’s world is off-balance. The set and cityscape are drenched in blue and lit in eerie blue, later also lilac (lighting design: Genevieve Larson).

(Chicago Cityscape Backdrop. Photo by Setje-Eilers.)

The stage area displays five large reproductions of vintage German posters, mostly from 1920s Weimar Germany, selected with the directors and hand-painted by Laura Streeter. They deserve close attention, for they relate surprisingly to our present political situation and parallel our own troubled dynamics.

(Views of Stage. Set Design: M. Streeter. Photo by Setje-Eilers.)

A poster with a nationalistic, red, German Imperial eagle filled with vertical organ pipes above the slogan “Germany the Land of Music” (Lothar Heinemann, 1937) almost touches the top of the electric piano, cleverly making it look like an organ. It’s reminiscent of the street organ in Brecht’s Threepenny Opera.

(Portrait of Dogsborough and electric piano with L. Streeter’s Adaptation of Music in Germany. Photo by Setje-Eilers.)

Käthe Kollwitz’s 1924 antiwar poster “Nie wieder Krieg” (Never Again War) at stage left calls out in vain for Ui’s crowd to resist preparations for yet another world war.

(L. Streeter’s Adaptation of Nie Wieder Krieg. Photo by Setje-Eilers.)

Only the audience can see the travel poster “Sommer in Deutschland” (Summer in Germany, Ludwig Hohlwein, 1927) at stage left. Yet, considering the signs we read at the entrance, who would want to go there?

(L. Streeter’s adaptation of Sommer in Deutschland. Photo by Setje-Eilers.)

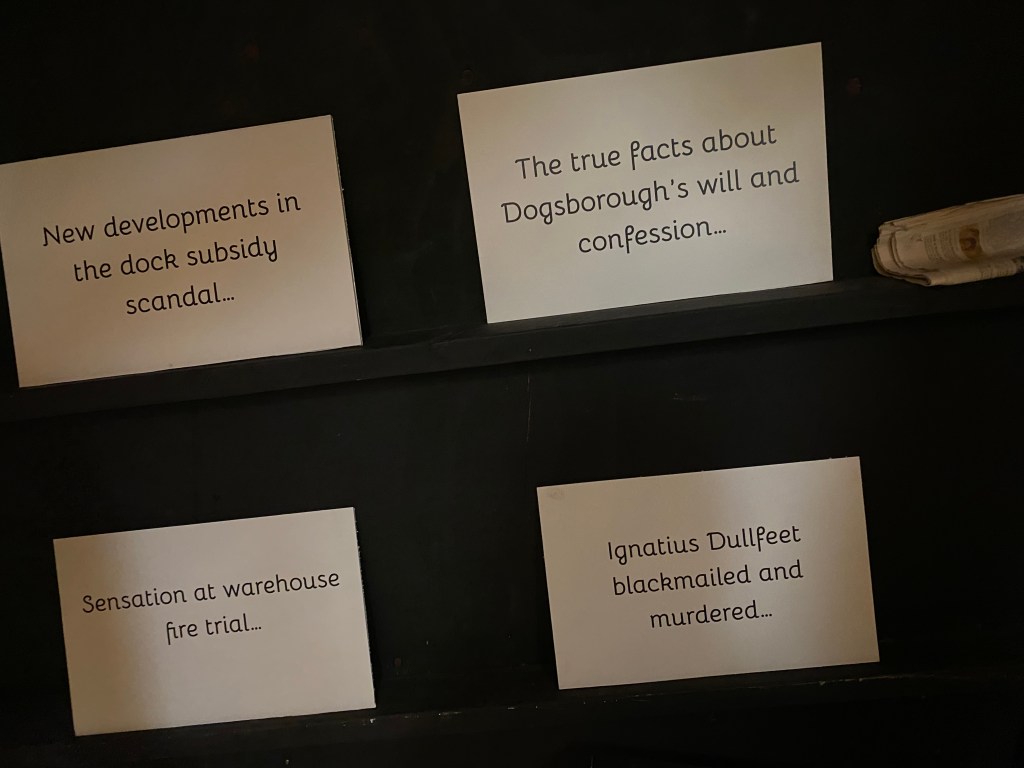

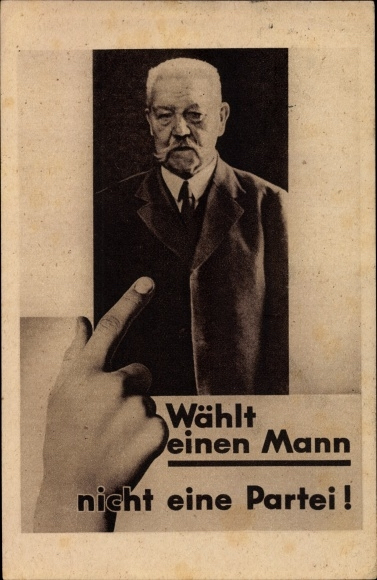

As part of the set on stage right, there is a very large portrait of Dogsborough (aka Paul von Hindenburg), with the name DOGSBOROUGH under it, based on a 1932 postcard.

(Left, 1932 Postcard. Right, Streeter’s Adaptation of 1932 Postcard. Photo by Setje-Eilers.)

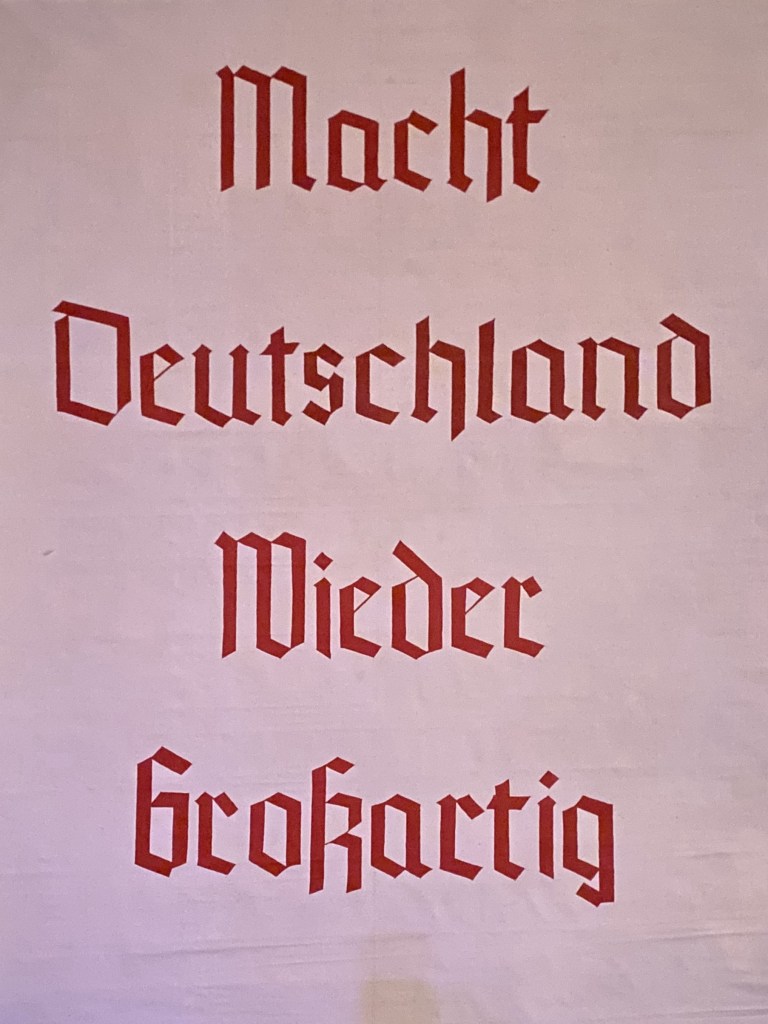

Hindenburg was President of the Weimar Republic when he appointed Hitler Chancellor of Germany in 1933. The slogan under the familiar face, “Wählt einen Mann, nicht eine Partei!” (Elect a man, not a party!) is a disturbing reference to our political present. I am astonished to see another type of warning on a poster to the right of the piano: “Macht Deutschland Wieder Großartig” (Make Germany Great Again).

(Poster: Make Germany Great Again. Photo by Setje-Eilers.)

Hitler made comments like this, if not these exact words, at least along this line of thought in his speeches. If we haven’t understood the parallels between the rise of Hitler and one of the candidates for our upcoming presidential election, this bold connection makes it obvious. If you read German, that is. It would have been helpful to translate this striking selection of posters, visuals, and texts in the online program (found at the bottom of this page).

The Twilight Theater has used downloadable programs for years to avoid paper waste, and its remarkable cover illustration for this play in fascist black-white-red is especially worthy of praise (cover by Chris Byrne). Against a red background, a man wearing a black suit and hat raises his right arm almost like a mock Hitler salute, but he holds a stylized white cauliflower like a bunch of flowers in his hand. He is outlined in white, and his left armband sports a large U with an “I” through it. It is Ui (aka Hitler). There was also a large printout of the program on the wall of the concession area and a pile of surveys for spectators to score each person in the production: directors, designers, actors, the entire cast, the play itself: “Just like the Tony awards, our awards are voted on by peers, like YOU! You’re not judging, you’re voting for your favorites!” Responsible voting with consequences, a positive complement to the ominous voting that takes place in the final minutes of the play.

The production is framed like the kind of vaudeville show that popped up in the USA in the mid 1890s to 1930s, a farce combined with music, here with appropriately lively tunes (accompanist: Tristan Colo) and an announcer (Leiner) who briefly introduces the characters. They swiftly appear and display identifiers like their hats and costumes. One actor even surprises with an unexpected, unforgettably evil giggle. During the scene changes with catchy musical accompaniment, actors perform tricks like juggling, a headstand, hand walking, conversing with a ventriloquist’s puppet, and doing magic tricks like pulling a coin from the ear of a member of the audience, straightening out a knot in a rope, and changing the color on a scarf. At the same time, somber projections on the backdrop, some with visuals, announce the German counterpart of the scene we have just seen in the Chicago world. The projections disappear rather quickly as props and people move around on stage. Probably a longer tech rehearsal time would have slowed them down. These slides are so good that I will include them here to illustrate how well they enhanced the production. It might have been helpful to add them to the online program for advance preparation. I would bet that some spectators at this theater didn’t know much about Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria (called the “Anschluss”) or that the Austrians voted almost unanimously (with the help of Nazi coercion) in favor of the merger of Germany and Austria. Since Brecht did not want to create dramatic suspense about what would happen next so that the audience would have clear heads for critical thought, giving spectators at the Twilight Theater a chance to bone up on these events beforehand would have been a nice Brechtian move.

Knowing the background is especially important because while the juggler is juggling, the production too, is juggling a virtual palimpsest of themes and historical eras in a mighty satirical allegory: Al Capone and the Mafia gangster world in 1920s Chicago (aka Arturo Ui and the Cauliflower Trust), Hitler’s rise to power in Germany, and the timely and menacing addition of the present-day Trump campaign. The effervescent accompanist Tristan Colo also juggles many kinds of music, starting out with a lively “Fashionable Vaudeville,” later including funeral marches and sounds like church bells, a thunderstorm, and gunshots, all perfectly timed (sound design: Michael Streeter). Together with Sam Halloway’s breathtaking acting – his Arturo Ui a splendidly hardened, nasty, knifelike meanness laced with humor – Colo propels the production onward and keeps his juggling balls high in the air during the whole show. According to Toner, co-director Tobias Andersen had acted in the show decades ago and wanted the kind of music that Colo provided. Brecht designed his plays to entertain as well as instruct, and the music here contributes much to the enjoyment.

Colo’s tunes accompany fourteen actors, which is a large cast for the small stage at the Twilight Theater, but in fact the play calls for even more actors, so that everyone except Ui and Roma plays two or three characters. It is a treat to experience this play as a close-up. In contrast, Heiner Müller’s 1995 excellent and legendary production at the Berlin Ensemble with Martin Wuttke as Ui had a vastly different viewing dynamic: twenty-nine actors, no double roles, with seating for 700. The Portland spectators have the benefit of immediacy. Being perpetually zoomed in on the action and its impending disaster only enhances the feeling of individual responsibility in every audience member to resist the resistible. In practical terms, the smaller cast in Portland also meant that most actors had to engage with and develop several characters, and this required more costume changes, with costumes memorable enough to show which character was which (costume design: Marychris Mass). I was never confused.

The gangster trio Roma-Giri-Givola and Ui retain their own visual identifiers: Roma (Christopher Massey) in a black suit, blue tie, blue hat band, and a red-lit cigar (aka Ernst Röhm, leader of the Storm Troopers or Brownshirts, i.e. the Sturmabteiling or SA); Giri (Zero Feeney) in a black suit with a flower in his lapel, starting with a black hat but donning the hats of each person recently murdered (aka Hermann Göring, Hitler’s second in command, President of the Reichstag); Givola (Will Futterman) the flower store owner in a brown suit with a brown hat and blue tie (aka Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda). Arturo Ui (Halloway) (aka Hitler, Al Capone, Donald Trump) is instantly recognizable in a black hat with a bright red band and a blue pinstripe suit buttoned over a red power tie. Ui’s pinstripe was Al Capone’s signature suit, and the addition of the bright red tie is a clever but chilling detail, a melding of Al Capone and Trump. Ui (as Al Capone) came to Chicago from New York, but he was not the only “son of the Bronx” as he describes himself. All the gangsters in the production, including the Cauliflower Trust, delight in the Italian American Bronx accents we know from gangster films.

(Chicagoans. Photo by Garry Bastian.)

Minutes after the announcer acquaints us with the main characters, the first projection transports us into the milieu of embezzlement and real estate trickery, past and present:

(Slide by M. Streeter.)

A headstand by an actor (Stephanie Crowley): the world is already topsy-turvy. Soon Dogsborough (Brent McMorris) finds he has fallen into a deep trap. He has awarded a loan to a shipping company of which he now owns the majority interest and has accepted a country house as a gift. In the allegory of Hitler’s rise, the loan and house point to the East Aid Scandal that incriminated Hindenburg. Projections:

(Slides by M. Streeter.)

At this point, the seemingly innocent stunts during the scene changes take on a metaphorical meaning in my mind: balancing on one’s hands, pulling a coin out of someone’s ear, and so on (most stunts by Adrian Crowne). I would like to see more time devoted to each trick, since moving the props on and off stage during the stunts is a bit distracting. Projections follow various events on stage:

(Slides by M. Streeter.)

However, Ui’s position changes drastically when he discovers he has a way to get what he wants from Dogsborough, whose financial shenanigans have made him a target for blackmail and bribery. Ui is in his element, exactly where he wants to be:

(Slide by M. Streeter.)

Ah, now the ventriloquist (Brian Young) comes out with the puppet. What a good choice: Ui, the ventriloquist, Dogsborough, the puppet.

Church bells and a drum roll signal that shipping company owner Sheet (not a role) has “committed suicide,” at least according to Ui, but we know it was murder. A gunshot, and now Sheet’s accountant Bowl (Crowley) is dead. The stuntman displays a long rope with a knot. He pulls it, and the knot disappears. Suddenly we understand that if there are now no more knots, there is no more trouble with bookkeeping for dock loans. Now I am certain that there is another level of meaning behind these stunts. Every single one has been carefully chosen. In honor of Bowl, Hook (Leiner) sings a few faltering lines of Judy Garland’s vaudeville-appropriate song, “Somewhere over the rainbow.” Here, the imagined place without trouble in the song is exquisitely ironic. Projection:

(Slide by M. Streeter.)

Along with the serious tenor of the intermittent slides, the action on stage, like Hook’s song, elicits a great deal of amusement.

The laughter grows to hilarity during the acting lessons that Ui (aka Hitler) takes from his teacher Mahoney (Leiner, filling in with great ease). Here, Ui learns how to walk, stand, sit, and speak. Ui apes Mahoney’s exaggerated rendition of Mark Antony’s speech from Julius Caesar by “Shakespeare, an English poet,” as he explains to Ui. Mahoney’s overplayed delivery is exactly the kind of classical acting style that Brecht critiques. Ui wears a blond wig for a bit, takes it off, gazes at it, then casts it to the back of the stage, disgusted. Both actors ham it up. Ui counts syllables on his fingers and gets mixed up at the end when he has too many syllables and no fingers left. Two projections:

(Slides by M. Streeter.)

Now that Ui can walk, stand, sit, and hold speeches – and since he now knows that Dogsborough is bribable – he uses his new skills to urge people to ask for his protection. Unity, sacrifice, protection, with Ui speaking for the “working man” while Dogsborough can only moan after he gets injections in his neck.

The combination of the production’s playfulness in scenes like the one with a sedated Dogsborough, the seriousness of the historical events, and the bouncy vaudevillian music carries out Brecht’s agenda for epic theater to the fullest. For example, when Hook’s warehouse burns, aka the Reichstag fire, someone waves bright flames on cardboard up high near the entrance to the seating area. “Fire!” (I dismiss thoughts of the theater fire in December.) Here we have the silliness of red and yellow cardboard flames and the seriousness of the Reichstag burning, together with its personal significance for Brecht, who left Germany the day after the fire, against the context of lively vaudevillian music and magic tricks. These are superb examples of the constitutive elements of Brechtian epic theater – image, text and music – working against each other to dispel the illusion of believing that what happens on stage is reality. According to Brecht, this interaction keeps the mind from being lulled to sleep, something he thought happened in illusionist theater, and instead frees it for critical thinking and reflection. There was no chance to sleep in this production. Projection:

(Slide by M. Streeter.)

During the trial after the warehouse fire, Fish (Brian Young) is accused of setting the fire and can only groan and ask for water after he, like Dogsborough, is sedated with injections. When Giri is questioned about his alibi at the time of the fire, he contradicts himself. He first insists he was in Chicago, then says Cicero – a suburb of Chicago, which later stands in for Austria. (Brecht’s choice of Cicero was ingenious, since Al Capone established his headquarters in 1920s Cicero.) The trial is full of corruption, coercion, and witness intimidation with mock ballet-like fights (fight choreography: Michael Streeter, Zero Feeney). Fun with Giri’s license plate: MAG445. Fish is evidently poisoned, and Giri sports a new hat. The stuntman displays a scarf that changes color. Ahh, I see. Projection:

(Slide by M. Streeter.)

In keeping with Brechtian strategy, whatever silliness transpires on stage, the action never appears as a continuous chain of events because the projections constantly interrupt the stage action and jolt us back into German history.

In addition to these interruptions, the scenes in epic theater are more or less interchangeable (except for some necessary historical chronology) instead of being causally arranged as in classical Aristotelian theater. Consequently, most scenes can move around without changing the message. Here, too the production makes use of this freedom. The melodramatic scene that comes before the epilogue in Brecht’s play appears here before the intermission. A woman (Melissa Standley) whose arm is injured and bleeding calls for help. “Where is everybody?” Silence. After the intense action on stage up to now, the stillness is compelling. No one comes but we hear machine guns as she falls, almost like in many U.S. cities today. The audience has much to ponder in the concession area during the break.

After the intermission, conspiracy theories abound on stage. The shipyard loan fund is gone because everyone has embezzled. Too close for comfort for Dogsborough, who writes a confession and his Last Will and Testament. Roma construes the confession as a way to keep Ui down and out of Cicero. But Ui wants the people of Cicero to follow him willingly. He has a “fanatical faith in the cause.” He insists, “I will find the road to victory.” This sounds too familiar. He agrees with Roma that there is a conspiracy against him. Projection:

(Slides by M. Streeter.)

Thunder, rain, and gunshots. Tommy guns (Thompson submachine guns, widely used in the 1930s by organized crime gangs) suddenly appear on the darkened stage and several sharpshooters run off into the audience (guns cut, routed, assembled, and painted by M. Streeter; master at arms: Georgia Ketchmark). Givoli shoots Roma. Giri now wears Roma’s hat with the blue band. Projection:

(Slide by M. Streeter.)

Following this murderous commotion is a contrasting, softly intimate scene with rhymed couplets, and we see Ui and Mrs. Dullfeet (Crowley) circle around and around calmly arm in arm, and likewise Givola and Mr. Dullfeet (Marty Baudet). This is, of course, a spoof on the scene in Goethe’s Faust where Faust woos Gretchen in Martha’s garden, while at the same time Mephistopheles woos Martha. Projection:

(Slide by M. Streeter.)

The juggler appears again, and Mr. Dullfeet’s gray hat lies on the floor of the stage. Another murder. With weighty allusions to Richard III, Ui courts Mrs. Dullfeet, who now stands in for Cicero (Austria). He tells her she needs protection, while at the same time she accuses Ui of murdering her husband. Projection:

(Slide by M. Streeter.)

Giri doffs the gray hat now, and the stuntman does a handstand and walks on his hands. Skillful balance, skillful negotiations. The play powers along on its own rhythmic dynamic.

Now that Roma is dead (and the path is clear into Cicero), his ghost comes to haunt and threaten Ui: Brecht’s nod to Macbeth. A dark stage, the ghost perfectly white: face, hat, tie, suit, shoes, shirt, with a single spot of red on the tip of his lit cigar (make-up by Christopher Massey; the actors did their own). The ghost removes his hat to show Ui a red bullet hole in his forehead: betrayal. “The people you struck down will rise against you!” Roma’s words hit home, for Ui and the political present.

But instead of an uprising, there is a meeting of minds as two large crowds – Ciceroans and Chicagoans – slowly approach each other and push together on the small stage. Giri wears Mr. Dullfeet’s gray hat. Standing on a cauliflower crate, Clark (Greg Shilling) (aka Franz von Papen, Ambassador to Austria) welcomes all Ciceroans to the Chicago Cauliflower Trust. Germany’s annexation of Austria is about to take place. On the crate, Ui explains that Dogsborough’s Last Will and Testament named him as the protector of Chicago. He emphasizes that he wants the Ciceroans and Chicagoans to elect him to protect them. There is to be no coercion: “Who is for me?” Gentle Mrs. Dullfeet climbs onto the crate and puts in a good word for Ui. Giri announces that it is time to vote. Everyone who is in favor of Ui is to raise their right hands. I realize that there are two large audiences now: the theater audience and Ui’s audience. The theater audience is implicated in its future action as it watches (and hopefully reflects on and learns from) what Ui’s audience does. Slowly, everyone on stage raises their right arms in hesitant and fearful, faltering and half-hearted Hitler salutes. It’s a chillingly tense moment: “Peace is reality in the Cauliflower Trust.” Now, under a spotlight on a darkened stage, the announcer delivers the alarming warning we know well from the play: “Although the world stood up and stopped the bastard / the bitch that bore him is in heat again.” Projection:

(Slide by M. Streeter.)

The vote that had catastrophic results for Austria abruptly reminds us of our own upcoming election.

Brecht wrote this play in Helsinki, Finland, in March 1941, while waiting for his visa to the USA, and he considered the play a warning for American audiences. He arrived in California in May 1941 and spent the next six years there. Although the English translation was quickly completed, and the first production in Germany was in 1958, it was not produced in the US until a very short run in 1963. Today, we are even more acutely aware than in the Nazi years that the world is disastrously out of balance in many crucial areas. We must thank the Twilight Theater Company, Dorinda Toner, and directors Tobias Andersen and Michael Streeter for recognizing that we have never needed their production more urgently. They left each member of their audiences with weighty issues to think about, most importantly that our actions will have serious consequences for the future if we don’t resist in all the ways we can, especially when we are asked to vote. For, as Brecht tells us, what seems inevitable is not.

Check out Margaret Setje-Eilers’ Conversation with Co-Director Michael Streeter here.