Overview

This guide is designed for students of the performing arts and their instructors as a pedagogical tool. Its purpose is to serve as a framework for applying a sociological perspective to literary and theatrical interpretation and production.

Objectives:

- Understand Marxism’s impact on Brecht’s sociological perspective.

- Identify limitations to the bourgeois theatrical heritage and understand how a sociological perspective overcomes them.

- Know several characteristics of the dominant ideology and how a sociological perspective counteracts it.

- Comprehend five core concepts of Brecht’s sociological perspective: Fabel, gestus, estrangement effects, historicizing, and experimentation.

Contents:

Introduction: Brecht’s Politics

Problems with the Bourgeois Theatrical Heritage

Fabel, Gustus, and Estrangement Effects

Historicizing and Experimentation

Introduction: Brecht’s Politics

Performing artists are often taught to think about narrative works in psychological terms. For example, actors frequently analyse characters based on the psychological processes behind their decision-making or how what the character encounters impacts their psyche and emotions. However, this is not the only perspective an artist can use while approaching the arts. This guide presents the performing arts student with a different approach to understanding and creating art: Bertolt Brecht’s sociological perspective. Unlike psychological approaches to understanding narrative works, which focus on how internal mental processes impact a character’s actions, Brecht’s sociological perspective is interested in what the characters’ actions reveal about society and social relations. Whereas the psychological approach wants to know how psychology impacts behaviour, the sociological perspective wants to know how society and social structures impact behaviour.

This guide outlines Brecht’s sociological perspective by discussing five key theoretical concepts he utilized in his creative process: Fabel, gestus, estrangement effects, historicizing, and experimentation. In short, key to Brecht’s sociological perspective is the creation of a Fabel, a composition of gestus, which are the underlying realities of human relations. The gestus is then presented for the audience to critically examine. This requires three things: 1) a historical awareness Brecht referred to as historicizing, which treats historical events as historically relative; 2) estrangement effects that produce a critical cognitive detachment in the audience; and 3) experimentation. Before we get too far into all this though, a little context about Brecht’s political ideas will be helpful.

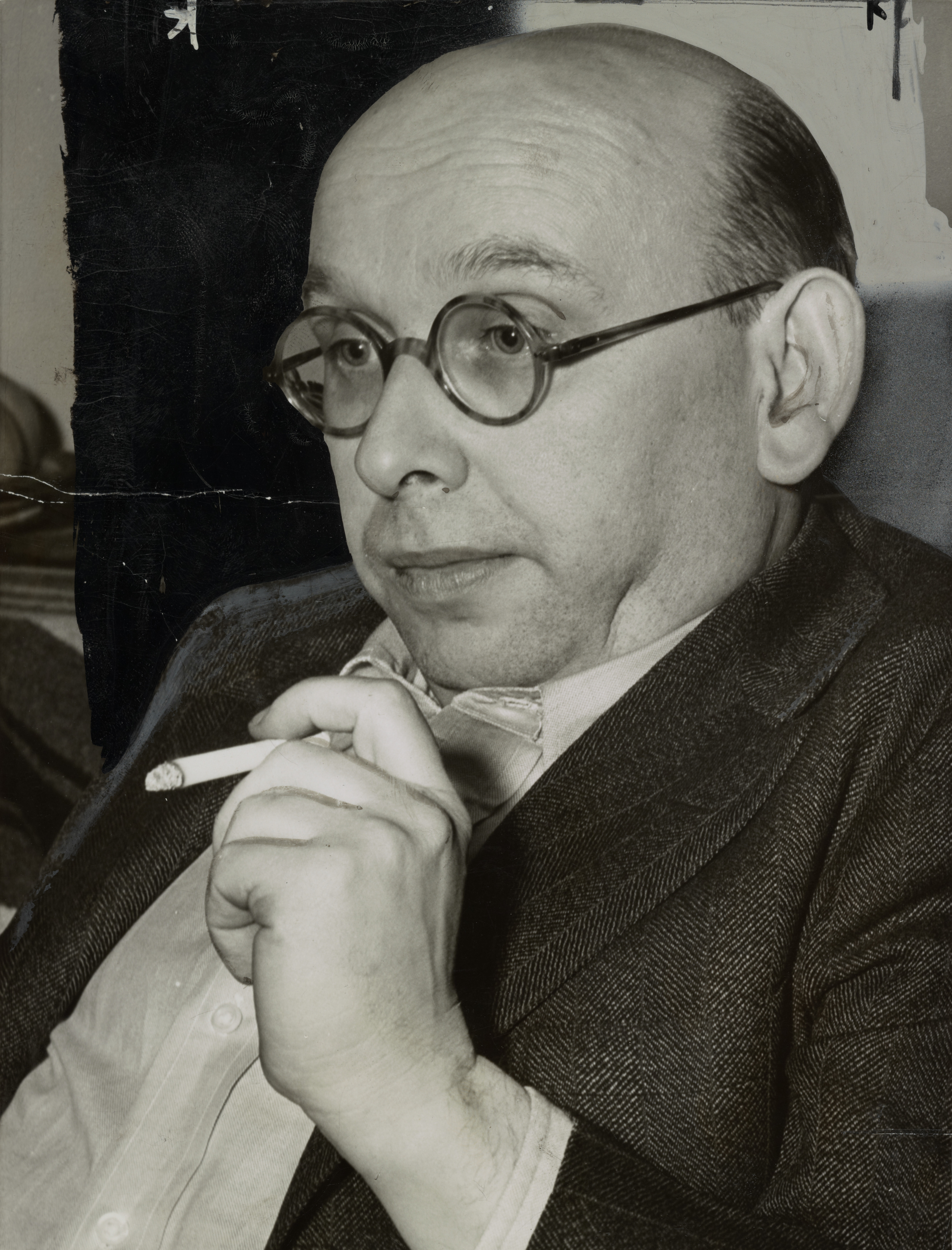

In the middle of the 1920s, Brecht was starting to become a prominent figure in German theatre. In 1922, he won the Kleist Prize, one of the most important literary prizes of Weimar Germany and he had earned critical acclaim for plays such as Drums in the Night, Baal, and In the Jungle of Cities. However, still in his 20s, he was far from the towering figure of Twentieth Century theatre he would later become. Nevertheless, in his early works, we see certain proclivities which later became hallmarks of his classic theatrical texts. For example, in them, one encounters penetrating social critiques and representations of class-based conflict. In 1926, these proto-Marxist tendencies starting to morph into overtly Marxist sentiments, when Brecht read works by Marx and Lenin for the first time. Brecht later reflected that “it was only when I read Lenin’s State and Revolution (!) and then Marx’s Kapital that I understood, philosophically, where I stood.”[1] It was as if “Marx was the only spectator for my plays I’d ever come across.”[2]

Reading those Marxist works would mark a monumental turning point for Brecht. Trying to get a better grasp of the kinds of social relations he wanted to depict on stage, Brecht was attracted to the social analytical clarity Marxism presented. In addition to expanding his reading in this area, he started attending Marxist discussion groups and lectures. Brecht attended events organised by philosopher, Karl Korsch and sociologist, Fritz Sternberg. Both men were influential writers and public intellectuals at the time and played significant roles in Brecht’s initiation into the Marxist canon[3]. By the 1930’s, in addition to being a prominent literary figure, Brecht was now a prominent Marxist figure with close personal and professional ties to many notable Marxist contemporaries. In addition to Korsch and Sternberg, this included Frankfurt School critical theorist, Walter Benjamin, novelist Bernard von Brentano, composers, Kurt Weill, Paul Dessau, and Hanns Eisler, as well as many others.

Marxism and Brecht’s Artistry

Marxism shaped Brecht as an artist in two primary ways, both of which are essential to understanding his work. First, it offered him an analytical framework for observing, understanding, interpreting and then representing the social world. This analytical framework is what philosophers and social scientists call dialectical materialism. In his Me-ti: Book of Interventions in the Flow of Things, a series of parables and aphorisms meant as an accessible primer on Marxist philosophical concepts, Brecht refers to dialectical materialism as the ‘Great Method’ and “a practical science”[4]. Essentially, dialectical materialism is a way of looking at the world in order to make sense of what’s going on. It is ‘dialectical’ because it sees reality in terms of a unity of opposites where natural progressions stem from the inherent contradictions within all things. In Me-ti,Brecht borrows from Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, to illustrate the concept of dialectics using the analogy of a bud. “The concept of a bud is already the concept of something trying not to be what it is.”[5] The bud turns into a blossom, which in turn becomes fruit. The bud, the blossom and the fruit are differentiated stages. However, as Hegel explains, “These stages are not merely differentiated; they supplant one another as being incompatible with one another. But the ceaseless activity of their own inherent nature makes them at the same time moments of an organic unity, where they not merely do not contradict one another, but where one is as necessary as the other.”[6] In Brecht’s words, dialectics can be understood as “alliances and dissolving alliances, of making use of changes and of dependence on changes, of bringing about change and changing those who bring it about, of the separation and formation of unities, of contraries’ lack of independence without each other, of the reconcilability of mutually exclusive contraries.”[7] This, he argued, “is (has always been) a property of nature…only discovered by Hegel and Marx.”[8]

Dialectical materialism is ‘material’ in the sense that it focuses on the material, observable world of things as opposed to the world of ideas. Through his readings of Marx and other Marxist theorists, Brecht came to accept Marx’s idea that history too worked dialectically, moving predictably, as successions of historically specific contradictions (which appear as class struggles) unfold and bring about new social conditions. In this process of social development, according to Brecht, “the new arises out of the old and is its next stage…The new comes about by upheaving, continuing, developing the old.”[9] This was, to Brecht a process of constant change. “[S]ocial existence,” he argued, “is continually developing.”[10]

Being able to comprehend reality in this way was a philosophical method of “inestimable value”[11] to Brecht. “[P]lays, especially with…historical content,” he maintained “cannot be written intelligently in any other framework,”[12] because it “enables us to recognize and make use of processes in things. It teaches how to ask questions that make action possible.”[13]

The notion of action[14] lies at the heart of the second primary way Marxism shaped Brecht as an artist. Marxism served as the foundation of a social purpose or cause to which he could lend his artistic talents. This purpose, according to Brecht “was not merely to arouse moral misgivings about certain conditions” but “to make visible the means by which those onerous conditions could be done away with.”[15] Above all else, Brecht was a Marxist revolutionary who used his art as a material intervention, a ‘weapon’ in the defining class struggle of the capitalist stage of historical development in which he found himself. At the core of this line of thinking is an emphasis on the importance of social theory informing artistic action. Brecht, himself understood this in terms of the dialectical interplay between social theory and artistic praxis (i.e., representations of the social world). He understood this dialectical interplay, in turn, in material dialectical terms i.e., in its relation to class struggle—a class struggle in which he was an active belligerent. For Brecht, the theories and practices he was wrestling with were interventionist implements capable of being weaponised by and for the subaltern classes for materially transformative purposes. For example, in 1934, while he was in the midst of systematising his ideas for his epic theatre, in a letter to Karl Korsch, he wrote, “[w]ith difficulty the workers…have learned to speak. We need to make use of their speech, along with the images and metaphors derived from their (conscious) life. Traditionally, theory is a kind of weapon.” [16] Elsewhere, along the same lines, he argued that “new methods for criticising ideas are to be deployed, and new ideas are to be constructed which are legitimised by their usefulness (weapons do not need to be charming for the person who needs them), and their use is to be measured in terms of their power to transform our societal world.”[17] Similarly, in an essay titled “Five Difficulties in Writing the Truth”, which was also written in 1934 and at one point published in leaflet form to be smuggled into Germany in resistance to the Nazis , Brecht contends: “anyone who wants to fight lies and ignorance and to write the truth…must have the courage to write the truth…the cleverness to recognise it [and] the skill to make it fit for use as a weapon” , further adding “we must think about how to convey the truth…in such a way that it can be a weapon.” In short, Brecht saw “the arts as a weapon in [class] struggle”[18] under capitalism.

Capitalism is an economic system that is characterized by the private ownership of the means of production. Simply understood, the means of production are the things needed to produce goods and services such as land, resources, machines, tools, or factories. In this stage, according to the Marxist view, there is an inherent tension between the class of people who own the means of production (the bourgeoisie) and the class of people who sell their labour working with the resources, tools, machines, etc. to produce things (the proletariat). This system results in great economic, political, and social inequalities where “the proletariat,” in Brecht’s words, “is held in bestial subjugation by the bourgeoisie”[19] through the “abuse of property for the purposes of exploitation.”[20] “[T]here [are] painful discrepancies in the world around us,” Brecht asserted, “conditions that [are] hard to bear…Hunger, cold and hardship…”[21] For Brecht, then, “The proletariat’s interest in the class struggle is clear and unequivocal.”[22] It is to remove themselves from the oppressive thumb of the bourgeoisie and to begin enjoying all the fruits of their labour, most of which is presently siphoned off by the bourgeoisie. This is an occurrence that is legitimatised, maintained and enforced through an intertwining system of economic, political, legal, and ideological strongholds which the bourgeoisie has set up ensuring their social advantage. In essence, the idea is that the bourgeoisie enriches themselves on proletarian labour, then converts that economic wealth into legal and ideological control over the workers. Nevertheless, Brecht argued “there can be no doubt that socialism…revolutionary socialism, will transform [this].”[23]

Much of Brecht’s theoretical writing in some way addresses the role of artists in helping to bring about socialist revolution. Specifically, he argued that revolutionary minded artists need to strive to represent the world “in a way that enables them to intervene in life itself, the life of class struggle, of production, of the particular spiritual and bodily needs of our age.”[24] This, he believed would be one part of the process of laying the foundation for a better future.[25]

Drawing on Marx’s understanding of history, Brecht believed capitalism would ultimately give way to communism, a historical phase where the means of production are owned commonly, eliminating the root-cause of inequality. However, before this happens, the proletarian class must have ‘class-consciousness.’ In other words, they must come to recognise that they are bound by common economic interests, see themselves as being in a common economic situation vis-à-vis the bourgeoisie, and then want to do something collectively about it. Brecht believed that he could help make that happen through his art by depicting the social relationships and material conditions that occur under capitalism. Once these realities are understood, the labouring class could band together and begin to alter them. To Brecht, these realities are alterable because they are historically determined, forged by the particular economic system of the time. Since economic systems change, social relations are also impermanent and transforming. Brecht states, for example:

We must be able to characterize the field in historically relative terms. This means breaking with our habit of stripping the different social structures of past ages of everything that makes them different, so that they all look more or less like our own age, which then acquires from this process a certain air of having been there all along, in other words for all eternity. We, however, want them to retain their distinctiveness and wish to keep in mind their transience, so that our own age too can be construed as transient.[26]

Stressing the impermanence of present conditions is crucial for Brecht, because it shows the progressive forces in society that their efforts to alter them have the potential to succeed. After all, as Brecht quipped, “Who wants to prevent the fishes in the sea from getting wet?”[27] To Brecht, social conditions stem from economic arrangements which are themselves human products. Social conditions are alterable because humans are responsible for creating them. They are not as he put it, “mysterious powers (behind the scenes), on the contrary, they are created and maintained by people (and are altered by them): they are constituted by people’s actions.”[28] So, for Brecht, “The fate of man is man [sic]”[29] and “human beings…do not have to stay the way they are; they may be looked at not only as they are now, but also as they might be.”[30]

In short, Marxism provided Brecht with the impetus for a radical reconceptualization of artistic practices as a means to equally radical social change. It inspired him to create a revolutionary aesthetics that was not only revolutionary in its departure from previous aesthetics but revolutionary in its social aims—a revolutionary aesthetics for a revolutionary cause.

Marxism and Brecht’s Biography

While Marxism had a significant impact on Brecht’s intellectual and artistic work, it also made an equally consequential mark on his biography. Brecht, being a Marxist of considerable renown, was forced to flee Germany with his wife, Jewish actor, Helene Weigel and their two children in 1933. Brecht himself left on February 28th, the day after the German parliament was set on fire. Almost immediately, Hitler and the Nazis began scapegoating communists for the arson attack in order to justify a crackdown on their political rivals. The Brecht house was even ransacked by the police in the aftermath. After a few turbulent weeks of displacement, the Brecht family, now refugees, landed in Svendborg, Denmark. Although they were temporarily safe from the Nazis, the family encountered real financial hardship there. Brecht and Weigel no longer had secure income and few prospects for obtaining it. Language barriers and a lack of professional contacts in the country made working in Danish theatre difficult for them. With productions largely out of the question for these reasons, in 1935, Brecht had time to devote to an essay which attempted to systematise some of his existing ideas for a new type of theatre, one that built upon the insights he gleaned through his Marxist studies. He referred to this new type of theatre as “epic theatre” which was, according to Brecht, “the broadest and most far-reaching experiment in great modern theatre.”[31] With a not-so-subtle nod toward Marx’s “Theses On Feuerbach,” Brecht claimed that with epic theatre, “The theatre became an affair for philosophers, at any rate the sort of philosophers who wished not just to explain the world but also to change it.”[32]

Changing the world became a more and more urgent task as Hitler consolidated power in Germany and then ordered his army to invade its neighbours. As Hitler advanced, Brecht was forced to retreat further and further. The family went from Denmark to Sweden, from Sweden to Finland and from Finland to the USA, trying to keep a step ahead. Brecht’s poem, “To a Portable Radio” captures the mood and fears of those unfortunate refugees during their flight:

You little box I carried on that trip/ Concerned to save your works from getting broken/ Fleeing from house to train, from train to ship/ So I might hear the hated jargon spoken

Beside my bedside and to give me pain/Last thing at night, once more as dawn appears/ Charting their victories and my worst fears:/Promise at least you won’t go dead again![33]

Brecht saw that his enemy was making great advances. These were, as Brecht put it, ‘dark times’; but, as the above poem attests, he never surrendered hope. As long as the radio didn’t go dead, as long as resistance was possible, Brecht would resist and indeed, in the midst of these dark times, during twelve years of political exile, Brecht revisited again and again the notion of a theatre with a sociological perspective as a vehicle of resistance. Perhaps the best representation of this can be found in his unfinished Messingkauf Dialogues, alternatively known as Buying Brass. This work is a fragmentary theatre script that Brecht experimented with as a device to explain his theoretical ideas about the theatre. The premise of the piece is that a philosopher, a thinly veiled version of Brecht himself, enters a theatre and over the course of several nights engages in a series of discussions with actors and other theatre practitioners. Each of these discussions, then reveals the Philosopher’s and thus Brecht’s attitude about the state of theatre and the need for radical alterations to it, in order to facilitate the social change he sought. One section, in particular, captures quite succinctly the general orientation Brecht has toward the theatre as someone who “wishes to apply the theatre ruthlessly to his own ends” by producing “accurate images of incidents between people and allow[ing] the spectator to adopt a standpoint.”[34] He states:

“I can only compare myself with a man, say, who deals in scrap metal and goes up to a brass band to buy, not a trumpet, let’s say, but simply brass…that’s how I ransack your theatre for events between people…To put it in a nutshell: I’m looking for a way of getting incidents between people imitated for certain purposes; I’ve heard that you supply such imitations; and now I hope to find out if they are the kind of imitations I can use.”[35]

We’ll delve into exactly what Brecht was getting at when he says, ‘events between people,’ ‘incidents,’ and ‘imitations’ below. But, for now, we can see that they constitute a malleable base-substance that can be used to shape his new theatre, a theatre for a revolutionary cause. Getting at this base-substance though requires a process of great alteration, a complete melting down and a reforging. So, what exactly was the problem with the theatrical heritage for Brecht? Why does it need such a thorough transformation?

Problems with the Bourgeois Theatrical Heritage

There are two interrelated problems Brecht identifies in the bourgeois theatrical heritage, problems he believed prevent it from being revolutionary or working toward a revolutionary cause. First, he argues that it is not scientific. Specifically, it does not integrate what Brecht believed was a major discovery in the science of social relations, dialectical materialism. In the theatre, he argued, “representations cannot turn out satisfactorily without knowledge of dialectics – and without making us aware of dialectics.”[36] Without dialectical thinking, art presents unrealistic depictions of social life, according to Brecht and in his mind, there is a very good reason for this—“The bourgeois class, which owes to science the advancement that it converted into domination by ensuring that it alone reaped the benefits of science, knows quite well that its rule would come to an end if the scientific gaze were directed towards its own undertakings.”[37] “The reason why the new way of thinking and feeling has not yet really penetrated the great masses of humanity,” Brecht argues, “is that the sciences, for all their success in exploiting and dominating nature, are being prevented by the class which owes its power to them, the bourgeoisie, from operating in another field where darkness still reigns, that of the relations people have to one another when exploiting and dominating nature.”[38] The bourgeoisie, then have a vested interest in preventing this type of ‘science’ from entering the theatre or art more generally. As a class, they are better off when the socially disadvantaged don’t understand the realities of their social existence—i.e., “class struggle, the legality of competition, unrestrained exploitation, the accumulation of misery via the accumulation of capital.”[39]

Second, not only does bourgeois theatre obscure social reality, the muddled representations of social life it depicts have the effect of producing as Brecht put it, “hypnosis, or is bound to produce undignified intoxication, or makes people befuddled,”[40] turning them “into a cowed, credulous, ‘spellbound’ crowd.”[41] Elsewhere, I address this point in a study of Brecht’s social philosophy arguing that for Brecht, the bourgeois theatre creates and reinforces an uncritical Weltanschauung, a worldview, which is not self-critical and unable to provide a meta-critique of itself. Since the Weltanschauung cannot critique itself, empirical illusions have no way of being exposed as such. They are uncritically accepted as reality and thus the possibility of their change is eliminated. This phenomenon makes Brecht very critical of bourgeois art. He believes it retards the progress towards his social ideal.[42]In Brecht’s words, for the spectators of bourgeois theatre, “anything that has not been altered for a long time seems to be unalterable. Everywhere we come across things that are too obvious for us to make the effort to understand them. What people experience among themselves they take to be ‘the’ human experience. A child, living in a world of old men, learns how things work there. The way things run is the way the child runs with things. Anyone bold enough to wish for something further would only wish for it as an exception.”[43] In his Messingkauf Dialogues, Brecht elaborates this idea further through the voice of the Philosopher, “Many of us…find the exploitation that takes place between men just as natural as that by which we master nature: men being treated like the soil or like cattle. Countless people approach great wars like earthquakes, as if instead of human beings natural forces lay behind them against which the human race is powerless. Perhaps what seems most natural of all to us is the way we earn a living.”[44]

According to the Brechtian perspective then people develop an uncritical and unconscious way of perceiving, interpreting and understanding their environment and subsequently uncritically accept the dominant worldview. Bourgeois theatre reinforces this process by lolling the audience through its perverse portrayal of reality and preventing the working class from seeing that the poor conditions they find themselves in are changeable. In this way, it stands as an obstacle to social change. In sum, for Brecht, bourgeois art is unrealistic, cognitively stupefying, and encumbers the advancement of socially liberating causes. Quite simply, it is too caught up in the reproduction of bourgeois ideology. Therefore, it cannot be used in its existing form. It must be melted down, reformed, reshaped, in order to be useful. This is why Brecht says for example, “it is not at all our job to renovate ideological institutions on the basis of the existing social order by means of innovations. Instead our innovations must force them to surrender that basis. So: For innovations, against renovations”[45].

The Bourgeois Ideology

We can see then that Brecht’s call to overhaul the theatre was at the same time, a call to overcome the bourgeois ideology which is reproduced by the theatre. While Brecht’s thoughts on the nature of this ideology are often fragmentary and scattered throughout various sources, it is possible to highlight several primary ways Brecht characterises it. To begin with, Brecht clearly saw it as the hegemonic or dominant ideology in society.

As he put it in Me-ti, “the ruling thoughts of the age are the thoughts of the rulers.”[46] But not only is it dominant, as we saw above, it is so dominant that it generally precludes any type of tests or challenges to its supremacy. In other words, the hegemony (a word closely associated with Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci) is so profound, so penetrating, so diffused, that it is simply taken for granted and the thought of it as something which could even be challenged rarely occurs to people.

Furthermore, Brecht contended that the hegemony of bourgeois ideology had a way of advancing the interests of the bourgeoisie. “[T]he question ‘what is true’” he maintained, “can no longer be resolved without the question ‘whom does this truth benefit.’”[47] For Brecht, bourgeois ideology and the ‘ruling ideas’ which emerge from it are not beneficial to all as is often claimed, for example in its defences of capitalism. Instead, they serve the interests of the ruling class and work against those of the working class.

Nevertheless, Brecht sees the bourgeois worldview and its dominance as merely a historical, as opposed to a permanent phenomenon. That is, the bourgeois ideology, like all ideologies is something which is created and reinforced by the particular social relations of the epoch. He states, “people’s consciousness depends on their social existence”[48] and “social being determines consciousness.”[49] Therefore, the bourgeois ideology is historically determined, not eternal, and as we will see below, it is something which is capable of being overcome.

Finally, related to Brecht’s critique of bourgeois theatre discussed above, Brecht believed that bourgeois ideology obscures the inherent contradictions in all things and seeks to present a unified totality. This, in turn, is reflected and made observable in bourgeois theatre productions. He states, “The bourgeois theatre’s performances always aim at glossing over contradictions, at the pretence of harmony, at idealization…None of this corresponds to reality and so must be given up by a realistic theatre.”[50]

Brecht sees this obscuring of contradiction as a means toward bourgeois totalising saying, “the society in which we live is such that we are dependent on assimilating things, and thus on methods that specifically turn all things into objects of assimilation.”[51] Brecht envisions a bourgeoisie that seeks to hide itself within the totality, to hide its self-interested pursuits within a universal narrative. To illustrate, he says for example that “our bourgeoisie thinks it is mankind”[52] and the bourgeoisie is “eagerly and desperately occupied with achieving a new totality.”[53] The reason the bourgeoisie attempts to create a totality is obvious for Brecht; he believes that it is done in an “attempt to give lasting shape to specific proposals of an ethical and aesthetic nature, and to confer on them a final, definitive character, in other words, the attempt of a class to give permanence to itself and to give its proposals the appearance of finality.”[54]

So how does the appearance of finality manifest? Brecht sees it as being embedded in a kind of language or narrative disposition which is articulated not just by the ruling class but also reproduced uncritically throughout all strata of society. This language sustains and preserves certain systems of classifications, conceptual differentiations, methodological assumptions, assertions, a logic, and conclusions. Originating from a definition of art as the “skill in preparing reproductions of human beings’ life together such as lead people to a particular kind of feeling, thought and action”[55], Brecht believed bourgeois narrative dispositions lead people to certain feelings and thoughts which in turn help produce certain actions. These feelings, thoughts and actions are beneficial to the bourgeoisie and help maintain the bourgeois order, as we just saw. Because of this, Brecht asserts that “[s]ociety cannot share a common communication system so long as it is split into warring classes.”[56] In other words, for revolutionary social change to happen the subaltern classes cannot rely on the language of the exploiter. “We know that the barbarians have their art,” Brecht proposed, “Let us create another.”[57]

How to Make Conscious Experience Possible

For Brecht, a new manner of articulation must be developed, a new language system must emerge if the radical social change he sought is to be realized. This is precisely where his ideas about a theatre with a sociological perspective comes into play. They offered a way to move past the hegemony of bourgeois ideology by communicating in a way that makes “the step towards conscious experience…possible.”[58]

As a dialectician, Brecht discerned a dialectical interplay between the ideological and the material, i.e., between theory and praxis. He understood that the way we imagine our world shapes our material realities and that those material realities mould the way we understand the world, which in turn plays back on the material realities, which subsequently plays back on our understanding ad infinitum. This is a ceaseless pas de deux between the ideological structure and material conditions which although characterised by tension between the two which results in changes to both, when left on their own these elements tend to be mutually reinforcing, mutually reassuring. The ideological mostly confirms the material, the material mostly verifies the ideological. Changes tend to be small, incremental. It is a tedious, protracted process which has the practical consequence of prolonging suffering and material horrors. Moreover, there is an undeniable psychological comfort to be found in it. It creates an assuredness and confidence. Under normal circumstances the material and ideological correspond so closely there’s hardly a hint that things could be different than they are presently. Other possibilities rarely emerge. People take their perceptions of the world for granted. They appear entirely natural, total, matter-of-fact, timeless. In this way, ephemeral, historically determined phenomena e.g., forms of economic exploitation, war, and human suffering assume a natural and everlasting guise and are consequently taken for granted.

Brecht’s solution to this is his theatre with a sociological perspective, which advocated for artists to be in “a critical, analytic engagement with the apparatuses that produce knowledge and experience in order to change them (both the apparatuses and the knowledge and experience).”[59] In other words, his answer is to intervene in the material world with artistic representations that make it impossible for the material to be allowed to comfortably, reassuringly correspond to the ideological and vice versa. It is to disrupt the accustomed material world by producing unaccustomed representations of it which when internalised into the ideological framework of spectators are cognitively unsettling and have the potential to awaken the latent revolutionary capacities of the exploited classes.

Brecht employed two primary approaches to help his audience break free from bourgeois ideological shackles: his techniques of cognitive disruption known as Verfremdungseffekte or estrangement effects, and portraying events as historically relative. Through these means, which are discussed in-depth below, Brecht sought to depict social conditions in a way where the audience would not be able to see things as natural, permanent, or unalterable but instead as temporary and alterable. The goal was to present reality in such a way that instead of uncritically accepting the social conditions of the time, the spectator will come to the conclusion, in Brecht’s words, that “[t]his person’s suffering shocks me, because there might be a way out for him.”[60] In other words, the goal is to create representations of the social world which compel the viewer to not accept the misery that results from capitalism and to not treat it as an unalterable fact of life; but instead as something which can and should be abolished. “What we intend, by means of our art,” Brecht contented, “is to wage war on the exploitation of man by man”[61] so that “the exploitation of man by man is impossible.”[62]

Conscious Experience and the Classics

Above, we saw that Brecht’s new theatre with a sociological perspective sought to move past the detrimental effects of capitalism by moving past the ideological predispositions which maintain it. This meant transforming the artistic apparatuses which uncritically reproduce those ideological predispositions and, in turn perpetuate them. Nevertheless, as we also saw, Brecht did not advocate for a complete eradication of past artistic endeavours to achieve this. Instead, he sought to recover something valuable and useful from it, the base substance he likened to brass in the Messingkauf passage we examined above. For Brecht then, classical texts presented both challenges and opportunities for his revolutionary theatre. On the one hand, he believed they contained useful components, the ‘events between people’ and the ‘incidents’ of which the Messignkauf’s philosopher spoke. But, on the other hand, he also thought the way these texts were being handled in the bourgeois theatre rendered them problematic for his revolutionary aims.

In 1954, Brecht and the Berliner Ensemble, a theatre he and Weigel founded with state subsidies in East Berlin, in 1949, were developing a series of adaptations aimed at revitalizing the classics. Around this same time, Brecht made the following note:

There are many obstacles to the lively performance of our classics. The worst are the theatrical hacks with their reluctance to think or feel. There is a traditional style of performance that is automatically counted as part of our cultural heritage, although it only harms the true heritage, the work itself; it is really a tradition of damaging the classics. The old masterpieces become, as it were, dustier and dustier with neglect, and the copyists more or less conscientiously include the dust in their replica. What gets lost above all is the classics’ original freshness, the element of surprise (in terms of their period), of newness, of productive stimulus that is the hallmark of such works…The passionate quality of a great masterpiece is replaced by stage temperament, and where the classics are full of fighting spirit, here the lessons taught the audience are tame and cosy and fail to grip…[63]

Brecht derided how the contemporary representatives of bourgeois theatre presented the classics. To him, it was merely a “Formalist ‘renewal’ of the classics” that was “as if a piece of meat had gone bad and were only made palatable by saucing and spicing it up.”[64] “Before undertaking to produce one of the classics,” he argued:

we have to see the work afresh; we cannot go on looking at it in the depraved, routine-bound way common to the theatre of a depraved bourgeoisie. Nor can we aim at purely formal and superficial ‘innovations’ that are foreign to the work. We must bring out the ideas originally contained in it…we must study the historical situation prevailing when it was written, also the classical author’s attitude and special peculiarities.[65]

In this short passage, we see several of the core elements to Brecht’s approach to the classic and his sociological perspective: seeing “the work afresh,” bringing “out the ideas originally contained in it,” studying “the historical situation.” In the sections that follow, we will tease out these ideas to reconstruct Brecht’s sociological perspective.

Fabel, Gustus, and Estrangement Effects

The Fabel

When Brecht approached a theatrical piece, he wanted to expose something about the structures of social interaction, what implications those structures have on the material conditions under which people live (and vice-versa) and what impact those conditions have on the behaviour of individuals. To do this, he began by shaping what he referred to as the story’s ‘Fabel’[66]. The Fabel is, as Barnett succinctly captures, “an interpreted version of events”[67] which examines “fictional events though the lens of real social contradictions.”[68] In essence, the Fabel can be understood as the core idea around which all of a work’s depictions of social relations are cantered. To illustrate, in his Mother Courage, the centralising concept is war. In his adaptation of Don Juan, it is conquest. These ideas give shape and context to the representations of social relations in the works. According to Brecht, the Fabel “is the theatre’s great undertaking, the complete composition of all the gestic incidents.”[69] But what exactly does Brecht mean here with the use of ‘gestic’ incidents?

Gestus

‘Gestic’ is the adjective form in English rendering of the German word ‘Gestus.’[70] According to the linguists who translated and edited the indispensable source for Brecht’s theoretical writings on theatre, Brecht on Theatre, 3rd Edition, “Etymologically Latin,” gestus “refers to physical bearing or body movement, especially of the hand or the arm. More specifically, it alludes to a speaker’s or actor’s use of gesturing…[it] refers to everything related to mime and mimicry, including facial expressions, body posture and body language, which contribute to the telling of a story.”[71] While admittedly Brecht’s use of the term and several derivatives of it varied somewhat over time and some seeming irregularity in its application can be found[72], it is nevertheless possible to reconstruct a coherent and functional understanding of Brecht’s conceptualization of the word from his writings.

To begin with, as Brecht states, gestus, “is not supposed to mean gesticulation: it is not a matter of explanatory or emphatic movements of the hands, but of overall attitudes. A language is gestic when it…conveys particular attitudes adopted by the speaker towards other persons.”[73] In other words, gestus isn’t about “illustrative or expressive gestures” but “socially significant gestures.”[74] It is “the entire complex of diverse, individual gestures, combined with utterances, that forms the basis of a discrete human incident and relates to the overall attitude of all those taking part in the incident (people condemning others, giving guidance, fighting and so on)…[it] traces how humans relate to one another.”[75] Throughout Brecht’s writings he offers several examples that can help illustrate what he was aiming at with the use of the word. For example, he mentions the gestus of: “exploitation[76]; “cooperation”[77]; “revolt against oppression”[78]; “shouting at one another”[79]; “showing”[80]; “beginning”[81]; “handing over a finished product”[82]; “making an assumption”[83]; “commanding”[84]; “keeping your mouth shut…looking about you…sudden fear.”[85] From these examples, we can see that gestus should be, as the editors of Brecht on Theatre astutely put it, “understood as a typical, recognizable form of behaviour.”[86]

Screaming. Adobe Stock.

Social Gestus

Brecht distinguishes between gestus, as a generally recognizable behaviour which can be displayed, represented, or signified to and understood by an audience and a more specific form of gestus he refers to as ‘social gestus.’ For a gestus to be social it has to, in Brecht’s words, represent “a social undertaking, an undertaking between people” or an “operation among people” and it has to allow “conclusions to be drawn about the social circumstances” being depicted.[87] For example, Brecht argues that, “[t]he attitude of chasing away a fly is not yet a social gestus, although the attitude of chasing away a dog may be one, for instance, if it comes to represent a badly dressed man’s continual battle against watchdogs. Someone’s efforts to stay balanced on a slippery surface results in a social gestus as soon as falling down would mean ‘losing face.’”[88]

Brecht’s theatre with a sociological perspective was particularly interested in revealing this social type of gestus. He states, “[t]he epic theatre is chiefly interested in the behaviour of people towards one another, wherever they are socio-historically significant (typical). It works out scenes where people behave in a way that makes visible the social laws under which they are acting.[89] Above, we saw that the Philosopher in the Messingkauf wants to ransack the theatre for ‘events between people’ and ‘incidents.’ When Brecht puts these words in his mouth, he means social gestic instances—those that make underlying truths about human relations apparent. From the standpoint of artistic production, capturing social gestus was absolutely essential for Brecht. “Every artist knows,” he insisted, “that subject matter in itself is in a sense somewhat banal, featureless, empty and self-sufficient. Only the social gestus…breathes humanity into it.”[90]

Gestus in Text

While the term gestus is indelibly linked to the idea of gesture, Brecht makes the point that gestus also “produces through language and word order an aesthetic image of the functional laws of a society.”[91] Additionally, as Oesmann perceptively points out, Brecht used the term of gestic speaking which he applied to his poetry but nevertheless “he did so while constantly thinking about theatre.”[92] Oesmann further adds that Brecht’s “struggle with the historical material” for his adaptation of Marlow’s The Life of Edward the Second of England, “led him to develop a language that signifies the complexities and contradictions inherent in historical events.”[93] In other words, it led him to develop a gestic language for the stage. It is therefore helpful to think of gestus more broadly as signification which can include spoken and written words. This sense of the term can be seen, for example when one says, “saying ‘thank you’ is a nice gesture.” In this sense, as in the Brechtian sense, the key is that an ‘actor’ is signifying something that is socially recognisable and meaningful. The delivery method of the signification could make use of different approaches and / or combinations of approaches including the use of written and spoken word, display through bodily movement, musical and visual aesthetic choices, etc.

Estrangement Effects

Brecht spent considerable amounts of his intellectual energies figuring out ways to reveal sociological truths about social relations. In order to be successful at this, however, he believed a sort of overcoming or end-around of the hegemonic (i.e. bourgeois) ideological order was required. What was needed, according to Brecht, was estrangement or de-familiarisation, something which would nudge the audience past the mystification of bourgeois ideology—an ideology which he believed had fully penetrated the theatre.

In order to de-familiarise and get past the obfuscation of bourgeois ideology, Brecht developed his famous estrangement effects, techniques he hoped would allow “us to recognize an object, but at the same time makes it appear strange.”[94] According to Brecht, “The object of the [estrangement effect] is to estrange the social gestus underlying every incident.”[95] In essence, their goal was to produce a critical cognitive detachment between the audience and what they were seeing represented.[96] This, he believed would knock the spectator off balance cognitively causing them to feel psychological uneasiness with their own understanding of the world. This psychological uneasiness, he felt would, in turn, alter their perception of the world so that the granted would no longer be taken for granted. In short, the idea was to make the familiar world seem unfamiliar so that the audience would become self-reflective anthropologists. “Brecht’s aim,” according to Jean-Paul Sartre is to show modern man to us…through gestures presenting action…making us discover ourselves as others…achieving an objectivity which I cannot get from my reflection.”[97] In other words, Brecht forces the audience to study their social world as if they were seeing it for the first time. This would lead them to pose sociological and historical questions about the material conditions and social relations of their time. Ultimately, Brecht hoped that they would come to see these conditions and relations as mutable and awaken in his audience a revolutionary impulse to change them.

Estrangement effects are often associated with developments Brecht made in the physical production of theatrical works e.g., approaches to acting, the physical arrangement of objects and actors on the stage, the relation of music to action or dialog, the use of various props and lighting techniques, etc. Classic examples of Brechtian estrangement effects would include things like having an actor step out of character during the performance, breaking the fourth wall, or using signs, placards, and projections in ways that would break up the action. His adaptation of Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz’s The Tutor provides a nice representative example of his estrangement effects. Between the third and fourth acts, Brecht adds a time-lapse sequence which was staged using a revolving stage and set to music from a music box that missed notes from time to time. On the stage, the audience saw how the characters lives were going as time passes. One was touring abroad in Italy, one was getting married, another was sewing diapers. Time was passing. As it did, the scenes were moving smoothly around, yet the musical accompaniment did not go smoothly. The missed notes had a jarring, discomforting effect which did not jive with the mechanical smoothness of the visual transformations. In this way, the commonplace events portrayed were shrouded in an ethos of strangeness. This, in turn forced the audience to take a step back from the passive consumption of those depictions. It compelled them to give some thought to them, to question them.

Brecht provides a good general illustration of what he was hoping for with his estrangement effects when talking about lighting, stating, “brilliant illumination of the stage…plus a completely darkened auditorium makes the spectator less level-head,” and “[i]f we light the actors and their performance in such a way that the lights themselves are within the spectator’s field of vision we destroy part of his illusion.”[98]

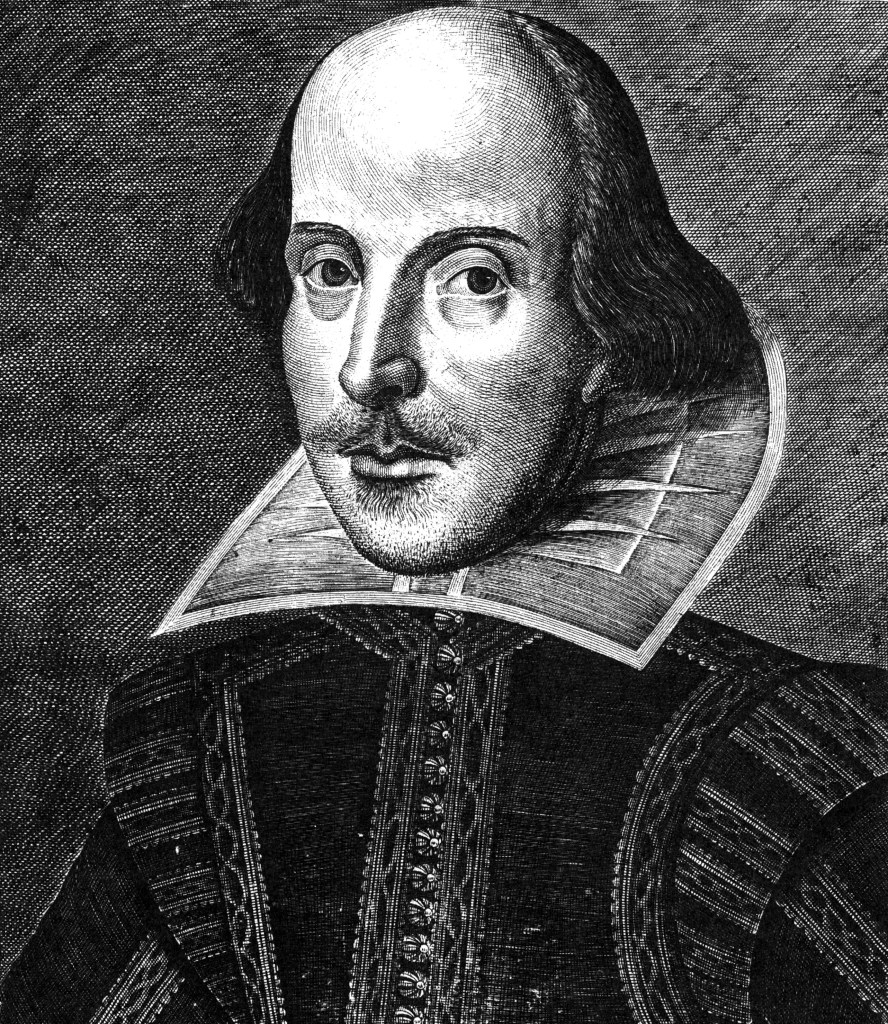

While estrangement effects are often associated with the physical aspects of production, techniques Brecht employed in the text itself were also designed to estrange. For example, Brecht would often set his plays in past epochs like feudal times or antiquity. Yet even though these stories were not set in capitalistic societies, Brecht was nonetheless representing capitalist society. This type of temporal transposition, i.e., superimposing truths about social relations under capitalism over the backdrop of past epochs with different economic and social systems was a common technique of estrangement for Brecht. It can be seen e.g., in his adaption of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus which is set in ancient Rome and in his play, The Good Person of Szechwan, which is set in ancient China. The later Brecht asserts was meant to reveal “the fatal effects of bourgeois ethics under bourgeois conditions.”[99] Brecht wanted to show his audience the conditions of their own world in estranged ways. He wanted to make the familiar unfamiliar. When Brecht depicts events in antiquity or feudal times, he is doing just that. He is depicting the problems of capitalism but in a strange guise. He relocates the realities into a different temporal frame which entices the audience to think, “Hey, that’s just like now!” Once they make this connection, they are then able to critically consider the current problems.

The use of estrangement effects were equally important to Brecht’s approach to his own works as they were to his approach to staging classical works. As we have already seen, for Brecht there was a use-value in the literary heritage.[100] In an ostensible exchange between him and Wolfgang Pintzka, an assistant director at the Berliner Ensemble, Pintzka says, “you are always dwelling on the need to learn from the old plays” to which Brecht responds, “The old must teach us how to make something new…there is much to be learnt from them. The invention of socially significant stories, the art of narrating them dramatically, the creation of interesting persons, the care for language, the putting forward of great ideas and the support of all that leads to social progress.”[101]

The problem is the things of value to be derived from these works is muddled or encumbered. Brecht addresses exactly this point when discussing operatic classics stating, “the old opera did contain elements that were not purely culinary[102] – we must distinguish the period of its rise from that of its decline – The Magic Flute, Figaro, Fidelio all had an activist dimension and embodied a world view.[103] However, in Brecht’s words, this content “was sidelined”[104] by the dominant (i.e. bourgeois) theatrical aesthetic. This aesthetic, as we saw above, relies on a ‘style of performance’ which is ‘traditional,’ that is to say habitual, long-standing, customary, and usual. Moreover, the style is ‘automatically counted as part of our cultural heritage’ and looks at works in a ‘routine-bound way.’ In other words, the bourgeois theatrical aesthetic relegates classical texts to the realm of the everyday, the ordinary, common-sense, the taken-for-granted, the seen but not considered. Because of this, there was a need for a rescuing of that which is of value in classic texts. This is where Brecht’s estrangement effects came into play. As he states, “the classical repertoire supplied the basis…The artistic means of Verfremdung [estrangement] made possible a broad approach to the current value of dramatists of other periods. Thanks to them such valuable old plays could be performed without either jarring modernization or museum-like methods, and in an entertaining and instructive way.”[105]

Through the application of estrangement effects, Brecht depicted events which were familiar and taken-for-granted in an effort to get his audience to see them anew and allow something about the social relations behind them to be revealed. Effectively, these effects served to estrange the audience from what they were familiar with. They sought to force the audience to understand the events afresh, as if it were for the first time.

We can see then the relationship between estrangement effects and the story’s Fabel. Estrangement effects are devices to help reveal all the gestus organised by the Fabel—the constellation of revelations about social relations. They are literary manoeuvres used to bring out what Brecht wanted brought out and critiqued about social relations.

In sum, estrangement effects are artistic moves made to reveal to the audience that which is present but overlooked,—to make the obscure obvious. The Fabel is Brecht’s particular telling of a story, a telling which has as its object to bypass bourgeois ideology to reveal the underlying workings of social relations (gestus) and their effects. Through the Fabel, Brecht aspired to represent in his theatre a collection of truths about social relations which have been extracted from bourgeois ideology and are put forth in a way so that they are ready to be observed and critiqued by the audience.

Historicizing and Experimentation

Historicizing

Brecht’s sociological perspective has the primary purpose of revealing truths about social relations. For that to happen, Brecht believed an awareness of the socio-historical context of the piece was indispensable. This idea is revealed for example, in ‘Study of the First Scene of Shakespeare’s ‘Coriolanus’’[106], a document which provides insights into the creative process of Brecht’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s play. In it, Brecht and others involved in the project make frequent references to the historical context of events portrayed in the source text. They analyse them, evaluate them, critique them and use their critique as the basis for changes to the source text. In essence, a historical sense guided the critique of the source text. This was Brecht’s notion of historicizing which he explained as, “judging a particular social system from another social system’s point of view.”[107] Brecht conceives of historicizing as “a crucial technical device” where depicted incidents are treated “as historical ones”[108] that are “ephemeral”[109] Moreover, “[T]he historicizing theatre,” according to Brecht, “concentrates entirely on whatever in [a] perfectly everyday event is remarkable, particular and demanding inquiry.”[110]

Brecht’s adaptation of Don Juan provides two fine examples of historicizing as a technical device. First, Brecht makes frequent comparisons between Don Juan and Alexander the Great, portraying Don Juan as embodying the ideal of conquest, a code of living from antiquity that Alexander represents. This portrayal of an ideal from an antiquated social system permits the audience to pass judgment on that social system from the point of view of another social system. Specifically, they can judge it from the medieval mindset of the play’s characters living in feudal times to see it as a thoroughly destructive way of thinking and they can critique it from their own modern perspectives to reach a similar conclusion. Second, Brecht has Marphurius, a doctor lament the decline of the antiquated feudal custom of duelling. This decline represents a loss of income for him since he is no longer able to treat the wounds inflicted during duels. However, while he simultaneously condemns the rising Bourgeoisie as barbaric, he also embodies the very same bourgeois characteristic he denounces, violence-profiteering. Seeing this, the audience then has the opportunity to pass judgement on an aspect of the bourgeoisie social system, violence-profiteering from the standpoint of their own social system.

As we already saw, Brecht understood history as a process in flux where human relations are changing and changeable. Within this conceptualisation, according to Brecht, “[h]istorical incidents are unique, transitory incidents associated with particular periods. The conduct of the persons involved in them is not fixed and universally human; it includes elements that have been or may be overtaken by the course of history and is subject to criticism from the immediately following period’s point of view.”[111]

The point of historicizing for Brecht is to make sure that events are seen “in historically relative terms”[112] to “keep their impermanence always before our eyes, so that our own period can be seen to be impermanent too.”[113] As the editors of Brecht on Theatre put it, “historicization shows that human beings can change,”[114] a major philosophical point for Brecht.

The approach to history found in Brecht’s theatre with a sociological perspective stands in sharp contrast to what one encounters in bourgeois theatre. According to Brecht, “The bourgeois theatre emphasizes the timelessness of its objects. Its representation of people is bound by the alleged ‘eternally human’…All its incidents are just one enormous cue, and this cue is followed by the ‘eternal’ response: the inevitable, usual, natural, purely human response.”[115] Brecht contends that even though “[h]istory applies to the milieu, not to Man,” in bourgeois theatre, “The milieu is remarkably unimportant [and] is treated simply as a pretext.”[116] But, in Brecht’s theatre with a sociological perspective the “idea of man as a function of the milieu and the milieu as a function of man, that is, the breaking up of the environment into relationships between people”[117] stands front and centre. This notion, Brecht contends, “corresponds to a new way of thinking, the historical way”[118] and is integrated in a “historicizing theatre,”[119] in which, Brecht argues, “everything is different. The theatre concentrates entirely on whatever in this perfectly everyday event is remarkable, particular and demanding inquiry.”[120] “What really matters” according to Brecht’s Messingkauf philosopher, “is to play…old works historically, which means setting them in powerful contrast to our own time. For it is only against the background of our time that their shape emerges as an old shape, and without this background I doubt if they could have any shape at all.”[121]

Experimentation

As we have already seen, Brecht’s philosophy is a philosophy of praxis. The idea is to use art as an intervention into the material world in order to spur on radical social change and eliminate the disastrous social effects of capitalism—to not only represent how the world is but to actively change it. Brecht sought to do this by using his artistic renderings to create a new type of awareness in the audience, an awareness that things can and should be otherwise than they are.

In the literary arts artistic praxis exists in the writing and publication of the text for its subsequent reading and can employ all the techniques discussed above. The Fabel is a textual construction. Gestus and estrangement effects have textual dimensions. Similarly, the conclusions derived through the process of historicizing are recorded in the text.

Nevertheless, in the performing arts additional steps are required in artistic praxis after writing, specifically those of the rendering i.e., production, staging, performing. While the Fabel and the product of historicizing belong largely to the domain of the text, gestus and estrangement effects go beyond their textual aspects. In the performing arts, the gestus must be displayed, presented, made apparent to the audience through the use of estrangement effects. The types of estrangement effects Brecht himself employed are well documented and discussed above.[122] However, as Owens incisively observes, “[t]he possibilities for a genuinely epic theatre” as Brecht practiced it “have become increasingly rare and difficult to sustain in the context of late capitalism’s tendency to flatten out distinctions and to reduce political discourse to style.”[123] Because even though they were once at the vanguard of dramaturgy, many of Brecht’s estrangement effects have been so widely adopted (not only in theatre but in cinema and television) they are now rather commonplace. Therefore, to produce the desired effect one would need to create new estrangement effects; one cannot simply recycle the old. While a full accounting of what types of estrangement effects could be effectively employed today to reveal gestus is beyond the scope of this guide, a few words along these lines are warranted here.

First, one must keep in mind the audience and social context for the performance. Estrangement effects are about making the familiar (i.e., the common-sense, everyday, ordinary, taken-for-granted, seen but not thought about) jump out, to seem strange, to stand out as an object for critique. What is familiar, ordinary, taken-for-granted, etc. is socially relative to some degree and has particular, localised manifestations. In terms of estrangement effects then, what might work to produce the right cognitive response in a Japanese audience might not work for a German one and vice-versa. Nevertheless, to the extent to which bourgeois ideology is the culprit in obscuring the tragedies of social relations produced by capitalism, there is a universality, points of general applicability in what the estrangement effects need to reveal and this universality extends as far as capitalism permeates. In other words, even though there may be localised variations and particular manifestations of the familiar which masks the reality of social relations, capitalism produces similar effects, irrespective of where it is practiced. Social gestus then transcends social context and its revelation can therefore serve as the basic aim for estrangement effects in all capitalistic social contexts.

Second, one must differentiate estrangement effects as a conceptual category from the particular techniques Brecht used to estrange in the past. Estrangement effects as a conceptual category are devices meant to reveal the realities of social relations that underlie events between people. Of course, Brecht tinkered with such devices, but Brecht’s estrangement effects do not constitute the universe of possible estrangement effects. They are simply the ones he invented and applied. Furthermore, as was just discussed, many of the estrangement effects Brecht came up with have been subsumed into the familiar and commonplace. Therefore, they no longer surprise or cognitively take-aback and are consequently unable to produce the desired effect of making the social gestus apparent to today’s audiences. Today’s artist, then, must be imaginative and endeavour to develop new effects, new techniques to cognitively titillate the audience, if they desire to awaken in them their latent revolutionary potential.

Finally, even when effective techniques are developed and implemented, history moves relentlessly forward. Things are constantly changing and in flux. This means that the social context in which one finds oneself and presents their artistic efforts is also in flux. Consequently, estrangement effects might have a limited lifespan. Just because they work at one point in time, does not mean they will work forever.

In the Brechtian theatre with a sociological perspective, everything is predicated on the estrangement effects compelling the audience to see the present but hidden realities of social relations. This, of course, is no easy task. We just saw that the social context of the production impacts the efficacy of estrangement effects and that the ones that do work might have a limited life expectancy. So, how does one get it right? The answer can be found in a final piece of Brecht’s sociological perspective, experimentation. At the end of the day, Brecht was result-orientated. He was constantly trying different things and he would put them to the empirical test to discover what works and what does not. He was always willing to reinvent. There was a permanent tentativeness to Brecht’s material interventions, an open, never final characteristic. Every work stood before him as an open question, even his own texts. For example, Carl Weber, a director who worked with Brecht at the Berliner Ensemble recounts a story where Brecht interrupted rehearsal of his play, the Caucasian Chalk Circle because he was unhappy with a particular line. “[H]e rewrote the scene,” Weber recalls, “He had looked at it as if it were by someone else, from a play he’d never seen before, which he was judging as a spectator, and it failed.”[124] As we can see, then, Brecht never really thought of any of his works as complete. In the implementation of Brecht’s sociological perspective, consequently, one must keep things open, un-foreclosed, available to criticism, and susceptible to alteration.

Summary

Brecht’s works are representations of the material world which were designed to undermine hegemonic ideology and produce cognitive uncertainty which would force people to conclude that humans are largely responsible for the construction of their ideological and material realities and that they are therefore not bound to how things are presently. This guide has outlined Brecht’s sociological perspective which was used to create representations toward this end. Specifically, it has shown that the key to the process is to create a Fabel, a coherent composition of gestic elements—the underlying realties of human relations. What is essential is revealing to the audience the social relations that lie behind the events portrayed. This requires three things. First, it requires a historical awareness (historicizing) which treats historical events as historically relative, stripping portrayed events of a timeless, natural, inevitable appearance and revealing them as transitory and alterable. Second, it requires the application of techniques that estrange, effects that remove realties of social relations from the domain of the customary, taken-for-granted, the seen but not observed and holds them out before the audience making them objects present and available for critique. Lastly, it requires experimentation. It requires an empirical orientation that is willing to try different things to figure out what works.

The five key Brechtian concepts addressed in this guide, Fabel, gestus, estrangement effects, historicizing, and experimentation are just some of the theoretical concepts Brecht employed in his sociological perspective. Nevertheless, they provide a simple and relatively straightforward framework which performing arts student can use to think about and interpret works, as well as apply to their artist output.

About the Author

Anthony Squiers, PhD, Habil. is a faculty member at AMDA College of the Performing Arts and co-editor of E-CIBS. He is the author of An Introduction to the Social and Political Philosophy of Bertolt Brecht and Bertolt Brecht’s Adaptations and Anti-capitalist Aesthetics Today.

Glossary of Terms

Bourgeois theatre: Theatre which reflects the ideology of the Bourgeoisie, the ruling class in capitalist society.

Bourgeoisie: The social class who owns the means of production.

Capital: Wealth in the form of money or other assets that is used or invested to generate more wealth.

Capitalism: An economic system that is characterized by the private ownership of the means of production.

Class-consciousness: When a social class become aware of its class interests and is willing to actively and collectively pursue them.

Class struggle: The antagonism that exists between different classes in society due to their conflicting interests.

Communism: A historical phase where the means of production are owned collectively.

Dialectical materialism: A philosophical framework used to understand the world. Derived from Karl Marx, it combines dialectics and an emphasis on the material conditions of life.

Dialectician: Someone who uses dialectics in their thinking.

Dialectics: A way of thinking about and understanding change, development, and relationships that sees reality in terms of a unity of opposites where natural progressions stem from the inherent contradictions within all things.

Epic theatre: Bertolt Brecht’s Marxist, experimental theatre.

Estrangement effects: Artistic techniques and devices used to make the familiar seem strange so that depictions are not taken for granted and the audience critically engages with them.

Experimentation: The empirical process of trying something to see what effect it has.

Exploitation: The unfair use of, or profit from someone’s labour.

Fabel: The core idea around which all of a work’s depictions of social relations are centered.

Formalist: Having to do with formalism, an approach to literature that focuses on the form and structure of a work (e.g., style and plot structure) rather than its socio-political content. The term is often used derogatorily by Marxists.

Gestus: A generally recognizable behaviour which can be displayed, represented, or signified to and understood by an audience.

Hegemony: A term closely associated with the Italian Marxist philosopher, Antonio Gramsci, who conceptualizes it as ideological domination by the ruling class, which maintains its dominance through tacit consent, not force.

Historicizing: Judging a social system from the point of view of another social system.

Idealization: Presenting something as perfect or better than it actually is.

Ideology: A constellation of shared beliefs, ideas, and principles about economic, political, and social organization.

Interests: In politics, interests are things individuals or groups want because they advantage or benefit them in some way.

Means of production: Tools, factories, land, and resources used to produce goods and services.

Milieu: The social context or environment in which a person lives or in which something takes place.

Praxis: A German word meaning “practice” or “practical application.” In Marxist thought, it is understood as human action designed to create a more economically just society.

Proletariat: The social class who sell their labour working with resources, tools, machines, to produce things.

Social gestus: A generally recognizable behaviour which can be displayed, represented, or signified to and understood by an audience and which reveals something about social relations.

Social relations: Interactions between two or more individuals or groups.

Social Structures: Relatively stable patterns of social behavior.

Society: A group of people who share a culture and live in the same territory.

Sociological: Having to do with sociology, the empirical, systematic study of society and human behavior.

Subaltern classes: The socially, politically, and economically marginalized or oppressed classes within a society.

Weltanschauung: A German word meaning a comprehensive worldview that shapes one’s perceptions and interpretations of the world.

[1] Brecht, Bertolt, Tom Kuhn, Steve Giles, and Laura J. R. Bradley. Brecht on Art and Politics. Methuen, 2003, p. 35.

[2] Brecht, Bertolt, and John Willett. Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic. Hill and Wang, 1992, p. 24n.

[3] Squiers, Anthony. “Brecht and Marxism.” Bertolt Brecht in Context, edited by Stephen Brockmann, Cambridge University Press, 2021, pp. 123–130.

[4] Brecht, Bertolt, and Antony Tatlow. Bertolt Brecht’s Me-Ti: The Book of Interventions. Methuen, 2016, p. 85.

[5] Ibid., p. 82.

[6] Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. “The Phenomenology of Mind.” Marxists.org, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/ph/phprefac.htm. Accessed 12 July 2022.

[7] Brecht and Tatlow, p. 85.

[8] Brecht, et al., 2003, p. 103.

[9] Brecht and Tatlow, p. 124.

[10] Brecht, Bertolt. The Messingkauf Dialogues. Methuen, 1965, p. 35.

[11] Brecht, et al., 2003, p. 154.

[12] Brecht, Bertolt, Hugh Rorrison, and John Willett. Bertolt Brecht Journals. Routledge, 1996, p. 372.

[13] Brecht and Tatlow, p. 85.

[14] This type of action is often fashioned in Marxist literature as ‘praxis’ which means practice in German in the sense of putting something into practice or practical action.

[15] Brecht, Bertolt. “Theater for Learning.” Brecht Sourcebook, edited by C. Martin and H. Bial, Routledge, 2000, p. 27.

[16] Brecht, Bertolt, and John Willett. Bertolt Brecht: Letters 1913–1956. Routledge, 1990, p. 187.

[17]Brecht, Bertolt, Tom Kuhn, Steve Giles, and Laura J. R. Bradley. Brecht on Art and Politics. Methuen, 2003, p. 112.

[18] Ibid., p. 308.

[19] Bertolt, et al., 2003, p. 341.

[20] Ibid., p. 134.

[21] Brecht, 2000, p. 27.

[22] Brecht, et al., 2003, p. 85.

[23] Ibid., p. 37.

[24] Ibid., p. 261.

[25] Squiers, Anthony. An Introduction to the Social and Political Philosophy of Bertolt Brecht: Revolution and Aesthetics. Brill ǀ Rodopi, 2014.Bottom of Form

[26] Brecht, Bertolt, Marc Silberman, Steve Giles, Tom Kuhn, Jack Davis, Romy Fursland, Victoria W. Hill, Kristopher Imbrigotta, and John Willett. Brecht on Theatre. Bloomsbury, 2019, p. 240.

[27] Brecht, Bertolt, John Willett, Ralph Manheim, and Erich Fried. Poems, 1913–1956. Methuen, 1979, p. 328.

[28] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 240.

[29] Brecht and Tatlow, p. 47.

[30] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 243.

[31] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 116.

[32] Ibid., p. 112.

[33] Brecht, et. al., 1979, p. 351.

[34] Brecht, 1965, p. 10.

[35] Ibid., p. 15-16.

[36] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 261.

[37] Ibid., p. 234.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Brecht, et al., 1996, p. 47.

[40] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 66.

[41] Ibid., p. 238.

[42] Squiers, 2014, p. 44.

[43] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 242.

[44] Brecht, 1965, p. 42.

[45] Brecht and Willett, 1992, p. 53.

[46] Brecht and Tatlow, p. 76.

[47] Brecht, et al., 2003, p. 111.

[48] Brecht, 1965, p. 35.

[49] Brecht, et al., 1996, p. 231.

[50] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 261.

[51] Brecht, et al., 2003, p. 104.

[52] Brecht, et al., 1996, p. 12.

[53] Brecht, et al., 2003, p. 97.

[54] Ibid., p. 98.

[55] Brecht, 1965, p. 95.

[56] Brecht and Willett, 1992, p. 196.

[57] Brecht and Willett, 1992, p. 189.

[58] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 256.

[59] Glahn, Philip. “Brecht, the Popular, and Intellectuals in Dark Times: Of Donkeys and ‘Tuis.’” Philosophizing Brecht: Critical Readings on Art, Consciousness, Social Theory and Performance, edited by Norman Roessler and Anthony Squiers, Brill, 2019, p. 133.

[60] Brecht, Bertolt. “Theater for Learning.” Brecht Sourcebook, edited by Carol Martin and Henry Bial, Routledge, 2000, p. 20.

[61] Brecht, et al., 2003, p. 194.

[62] Ibid., p. 137.

[63] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 275-6.

[64] Ibid., p. 276.

[65] Ibid.

[66]This is most often rendered in English as ‘plot’ or ‘story’.

[67] Barnett, David. Brecht in Practice: Theatre Theory and Performance. Bloomsbury Methuen, 2015, p. 86.

[68] Ibid., p. 89.

[69] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 250.

[70] Because of the inherent difficulties of finding an adequate translation for the word Gestus in English while maintaining all the Brechtian connotations, the editors of Brecht on Theatre chose to transpose the word directly into English and follow the English convention of starting common nouns with lowercase letters. In the interests of scholarly continuity, the same will be done in this guide, henceforth.

[71] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 6. See also: Mumford, Meg. “Getting to the Gist of Gestus.” Bertolt Brecht: Critical and Primary Sources Vol. II, edited by David Barnett, Bloomsbury, 2020, pp. 39–56.

[72] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 6.

[73] Brecht and Willett, 1992, p. 167.

[74] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 126.

[75] Ibid., p. 253.

[76] Ibid., p. 119, p. 272.

[77] Ibid., p. 272.

[78] Ibid., p. 119.

[79] Brecht, et al., 1996, p. 409.

[80] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 253.

[81] Brecht, et al., 1996, p. 207.

[82] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 253.

[83] Ibid., p. 253.

[84] Ibid., p. 171.

[85] Brecht, et al., 1996, p. 13.

[86] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 106.

[87] Ibid., p. 168.

[88] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 168.

[89] Ibid., p. 272.

[90] Ibid., p. 169.

[91] Ibid., p. 106.

[92] Oesmann, Astrid. “Art as the Speaker of History.” Bertolt Brecht: Critical and Primary Sources Vol. II, edited by David Barnett, Bloomsbury, 2020, p. 74.

[93] Ibid.

[94] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 241.

[95] Ibid., p. 187.

[96] Squiers, Anthony. “A Critical Response to Heidi M. Silcox’s ‘What’s Wrong with Alienation?’” Bertolt Brecht: Critical and Primary Sources Vol. II, edited by David Barnett, Bloomsbury, 2020, pp. 32–38.

[97] Sartre, Jean-Paul. Sartre on Theater. Pantheon Books, 1976, pp. 62–63.

[98] Brecht and Willett, 1992, p. 141. For more on Brecht’s estrangement effects see: Brecht, et al., 2019 and Willett, 1977. Furthermore, Brecht sometimes provides accounts of the various estrangement effects attempted in his productions. These can be found in Brecht’s notes to some plays (e.g. Life of Galileo, Mother Courage, his adaptation of The Tutor, etc.) and can be found in the notes sections of the collected volumes of his plays.

[99] Brecht, Bertolt, and John Willett. Bertolt Brecht: Letters 1913-1956. Routledge, 1990, p. 409.

[100] However, not all classical texts were equally useful for Brecht. In his words, “works like Shakespeare’s and…the earliest works of [German] classic writers (including Faust),” “hold [the] most promise” because of their “attitude to their social function: representation of reality with a view to influencing it” (Brecht and Willett, 1992, p. 225).

[101] Brecht and Willett, 1992, p. 250-251.

[102] By culinary Brecht means having no socially redemptive quality. Culinary works are “tasteful” because they don’t help produce social disruption and don’t produce “a guilty conscience” (Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 64) According to Brecht, culinary art, “seduces the [spectator] into an act of enjoyment that is enervating because it is unproductive” (Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 129). Culinary art is defined by a passive consumption which stands in opposition to Brecht’s philosophical theatre which requires active intellectual engagement from the audience.

[103] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 67.

[104] Ibid., p. 68.

[105] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 145.

[106] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 285-298.

[107] Brecht, et al., 1996, p. 82.

[108] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 187-8.

[109] Ibid., p. 143.

[110] Ibid., p. 157.

[111] Ibid., pp. 187-8.

[112] Brecht and Willett, 1992, p. 190.

[113] Ibid., p. 190.

[114] Brecht, et al., 2019, p. 104.

[115] Ibid., p. 156.

[116] Ibid.

[117] Ibid., p. 157.

[118] Ibid.

[119] Ibid.

[120] Ibid.

[121] Brecht, 1965, pp. 63-4.