Berlin has long been the heart of artistic rebellion, and nowhere is this more vividly encapsulated than at Das Kleine Grosz Museum. Nestled in one of the city’s most culturally significant neighbourhoods, Schöneberg, the discord of 1920s and 1930s Berlin is displayed through the sharp-edged works of George Grosz. Das Kleine Grosz Museum, a relatively new addition to Berlin’s storied artistic landscape, offers more than just a retrospective of Grosz’s work; it provides a journey into the psyche of a society unravelling under the weight of its own contradictions.

A few weeks ago I went to see the museum’s exhibition titled “Was Sind das für Zeiten? – Grosz, Brecht & Piscator”, open between 4 July and 25 November 2024. The space itself is very cosy. Housed in a gas station from the mid-20th century with bamboo, cherry bushes and a koi pond, the museum space feels like a break from the hustle and bustle of Berlin.The two-storied building displays Grosz’s work in a circular arrangement that works conducively with the focal points that the curators seem to want to highlight. On the first floor the curation briefly investigates Grosz’s early work, with descriptions of his early influences such as Dadaism. Upstairs is where Grosz’s production work for Brecht and Piscator is explored. This area evokes the feel of an art studio. Walking back downstairs, the museum wraps up with Grosz moving to America after fleeing Nazi persecution. The art from his American exile, hung on the wall opposite his early work, is much more existential. This well-made display choice dissects the difference between his work while living in Germany and the political work from his exile.

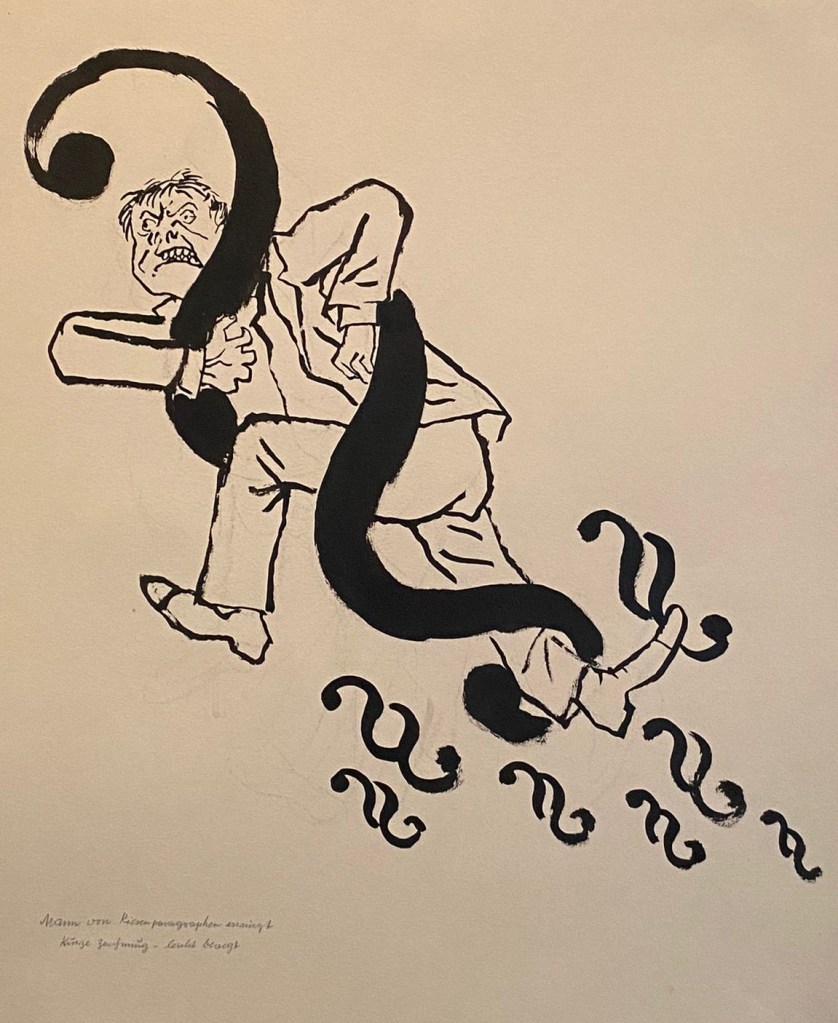

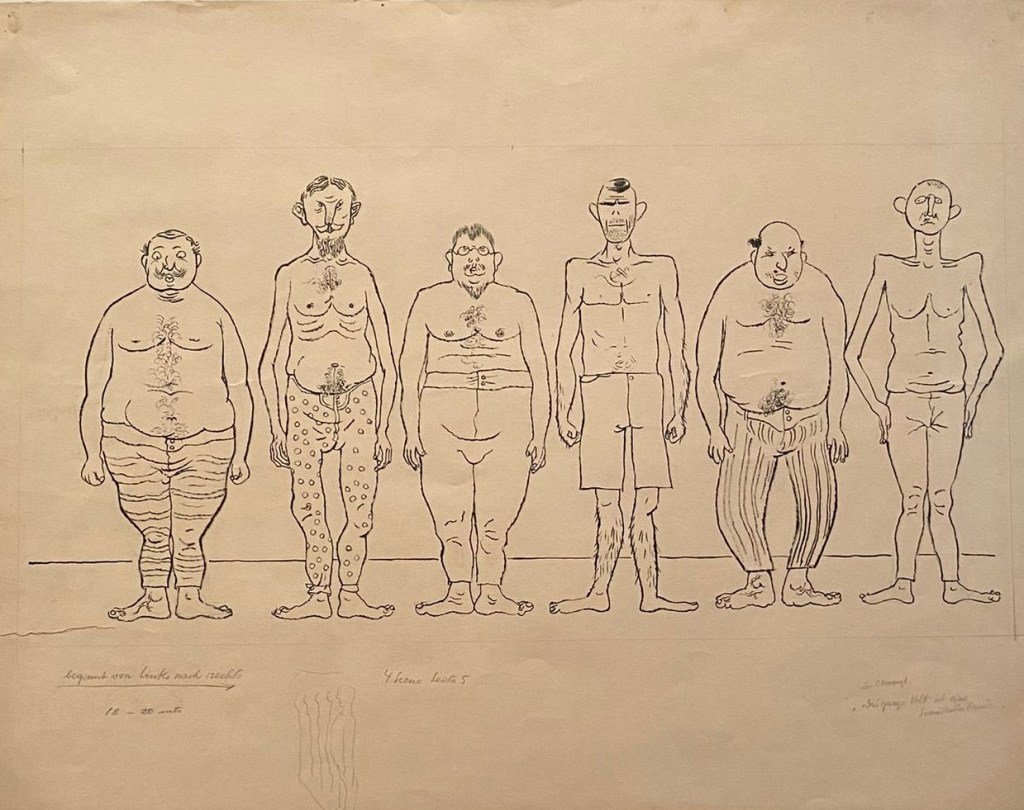

George Grosz’s early work, as displayed in the museum’s exhibition, offers a glimpse into the turbulent spirit of early 20th-century Germany. These pieces, created in the years leading up to and during World War I, are a striking mix of satire, social criticism, and gritty emotion, revealing Grosz’s deep disillusionment with society and the human condition. In his early drawings and paintings, Grosz employs a sharp, almost brutal line, with exaggerated forms that border on the grotesque. His characters—often depicted as bloated, corrupt figures of authority or desperate, downtrodden souls—are caricatures that reveal the moral decay and rampant inequality he saw around him. The chaotic energy of these works, coupled with their harsh, angular forms, conveys a sense of urgency and outrage, as if Grosz were issuing a desperate plea for change. Grosz’s ability to capture the anxieties and tensions of his time certainly cements his reputation as a pivotal figure in modern art. While Grosz’s early pieces are undeniably impactful, they are also overwhelming in their bleakness and intensity. His relentless focus on the darker aspects of human nature and society could lead to his work being seen as excessively cynical or nihilistic, lacking in hope or the possibility of redemption.

George Grosz’s involvement in the Dada movement marks a pivotal chapter in his career, adding an anarchic edge to his already sharp critique of society. The George Grosz Museum’s display of his Dadaist works captures this period of artistic experimentation, where his biting satire found new forms of expression. Dadaism’s disdain for conventional art and embrace of absurdity aligned with Grosz’s disillusionment with the world around him. His chaotic blend of collages, photomontages, and drawings disrupted traditional notions of composition and meaning, reflecting his rejection of the status quo. At their best, Grosz’s Dadaist works deliver scathing critiques of society through disjointed imagery and chaotic composition, capturing the disorientation of the post-war era. However, these same qualities can also lead to a sense of fragmentation that borders on incoherence. While undeniably provocative, Grosz’s Dadaist works sometimes prioritise shock and absurdity over deeper meaning, occasionally straining to communicate more than mere provocation.

Georg Grosz’s contributions to Erwin Piscator’s stage adaptation of Jaroslav Hašek’s The Adventures of the Good Soldier Schwejk represents a significant intersection of his artistic vision with the satirical literature of the time. Grosz was responsible for the play’s set design and visual elements, which were integral to Piscator’s preferred theatrical method, agitation propaganda. Piscator and Grosz rejected the traditional fourth wall of theatre, aiming instead to engage the audience directly in the political themes of the play. This is where Bertolt Brecht’s influence on the production becomes evident. Both Brecht and Piscator were pioneers in epic theatre, and sought to engage audiences more intellectually than previous theatrical genres had. They sought to stimulate critical reflection about social and political issues rather than provide pure entertainment or emotional catharsis. Brecht’s influence can be seen in how Schwejk was staged to create an alienation effect (Verfremdungseffekt), a hallmark of epic theatre that encouraged audiences to view the characters and situations critically, rather than getting swept up in the narrative or identifying with the characters emotionally. While Piscator was the driving force behind the stage adaptation of Schwejk, Brecht’s presence in the Berlin theatre scene influenced Piscator’s direction.

Photograph by Layla Esleben

Grosz’s artwork and settings were not just decoration but integral to the narration, intended as elements of dissenting thought which supported the satirical anti-authoritarian notions behind Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek’s source novel. Grosz’s drawings for Schwejk capture the dark humour of Hašek’s story. The characters are rendered in Grosz’s typical style—bloated, misshapen, and often imbued with a sense of menace or foolishness. Through these illustrations, Grosz not only visually represents Hašek’s narrative but also injects his own scathing commentary on the senselessness of war and the hypocrisy of those who wage it. These works are emblematic of Grosz’s ability to distil complex socio-political critiques into potent, often disturbing images. While still working on his drawings for Schwejk, Grosz became even more engaged with leftist intellectual groups in Berlin, where he met Brecht. Like Grosz, Brecht disapproved of bourgeois society and the political systems that caused wars and economic crises. Their shared interests formed a strong bond between the two artists. Grosz’s work for The Adventures of the Good Soldier Schwejk not only demonstrates his ability to convert literary satire into visual art, but was also significant for connecting him with Brecht. Later, their paths further intertwined through The Threepenny Opera.

Bertolt Brecht and George Grosz forged a bond through their shared political beliefs and their mutual contempt for the social and economic disparities prevalent in Weimar Germany. Their joint effort on The Threepenny Opera showcased this alignment as Grosz’s grotesque set designs added depth to Brecht’s scathing tale of corruption, greed and class conflict. Grosz’s exaggerated portrayals of characters and settings mirrored Brecht’s critical depiction of society, creating an immersive theatrical experience that pushed boundaries. His artwork vividly brought Brecht’s concept of theatre to fruition, enhancing the effect by keeping audiences critically engaged with the issues being addressed. The Little Grosz Museum showcases the importance of Grosz’s artistry in enhancing the success of The Threepenny Opera not only as a theatrical performance but also as a complete artistic creation. His dark and cynical visuals served as a satirical backdrop intensifying the play’s critique of society and compelling the audience to grapple with the hypocrisy and injustices ingrained in a capitalist system. Grosz’s contributions elevated the production into a more potent commentary on moral decline, bridging the realms of visual art and theatre. Through his work he ensured that Brecht’s message resonated with audiences in a way prompting reflection, solidifying their collaboration as a key moment in both German cultural history and contemporary art.

George Grosz’s collaboration on The Threepenny Opera not only amplified the play’s critical themes but also redefined the role of visual art in theatre. His grotesque, satirical style seamlessly integrated with Bertolt Brecht’s vision of epic theatre, providing a visual layer that deepened the audience’s experience of the narrative’s biting social commentary. The Little Grosz Museum’s focus on this partnership underscores the importance of Grosz’s contributions, highlighting how his artwork enhanced the play’s atmosphere and reinforced its portrayal of societal corruption. Grosz’s ability to capture the chaotic, morally bankrupt world of The Threepenny Opera added a powerful, immersive dimension to the performance, elevating it beyond a simple stage production into a fully realised artistic and political statement. Grosz’s work remains a testament to the enduring impact of visual design in shaping the tone and message of theatrical performances, proving that art and theatre, when combined, can deliver a profound critique of the world.

Layla Esleben is an undergraduate student at the University of Toronto, studying comparative literature and theatre with a minor in German studies.