Saint Joan of the Stockyards has finally arrived in Slovenia. “At last,” some might say, given that the text was first translated into Slovenian back in 2018. It was a long wait for this translation, but it was well worth it, as translator Mojca Kranjc did an exceptional job. Six years later, the first Slovenian staging of the play has finally taken place. And what a major international co-production it turned out to be.

The project brought together a remarkable lineup of institutions, including Emilia Romagna Teatro ERT/National Theatre, Mladinsko Theatre in cooperation with Cankarjev dom, TNL – Luxembourg National Theatre, Teatro Stabile di Bolzano, and the artistic collective ErosAntEros – POLIS Teatro Festival. It was nothing short of a grand spectacle.

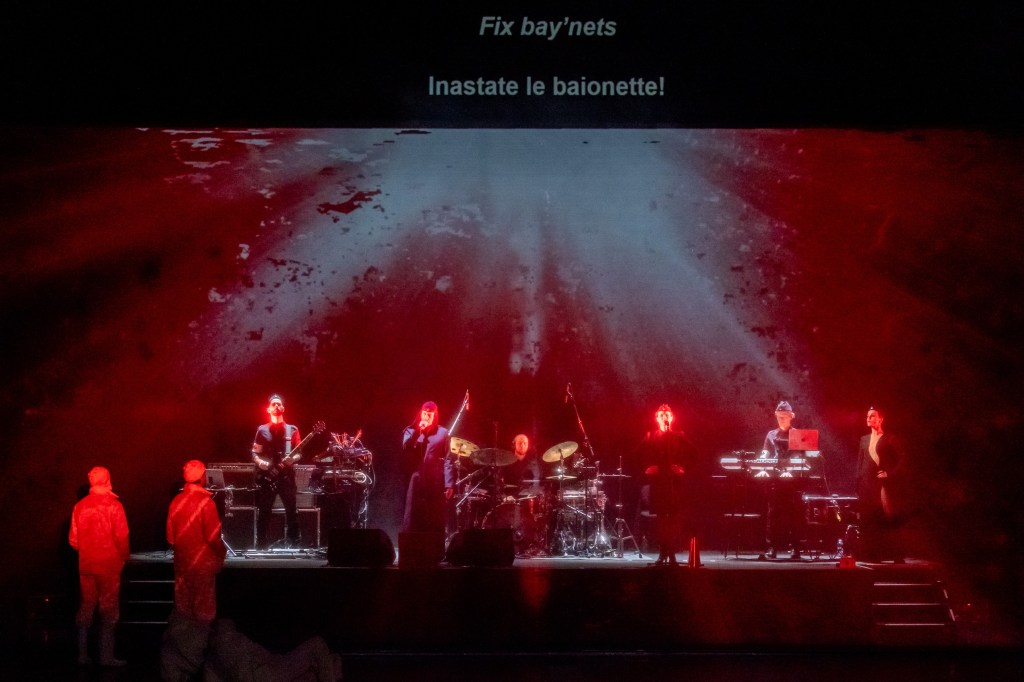

Not only did the production feature a cast of actors from three different countries, but it also included the renowned avant-garde music group Laibach, whose signature aesthetic and electro-industrial sound played a prominent role. The production further incorporated an array of technological elements, such as video projections, Zoom calls, documentary footage, and large-scale visuals.

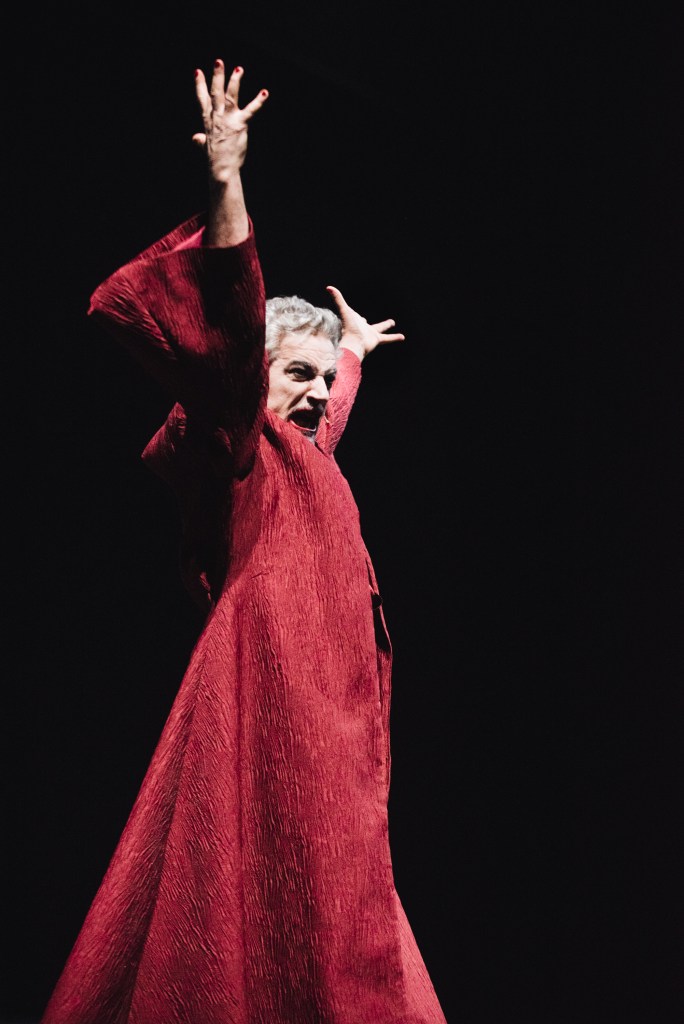

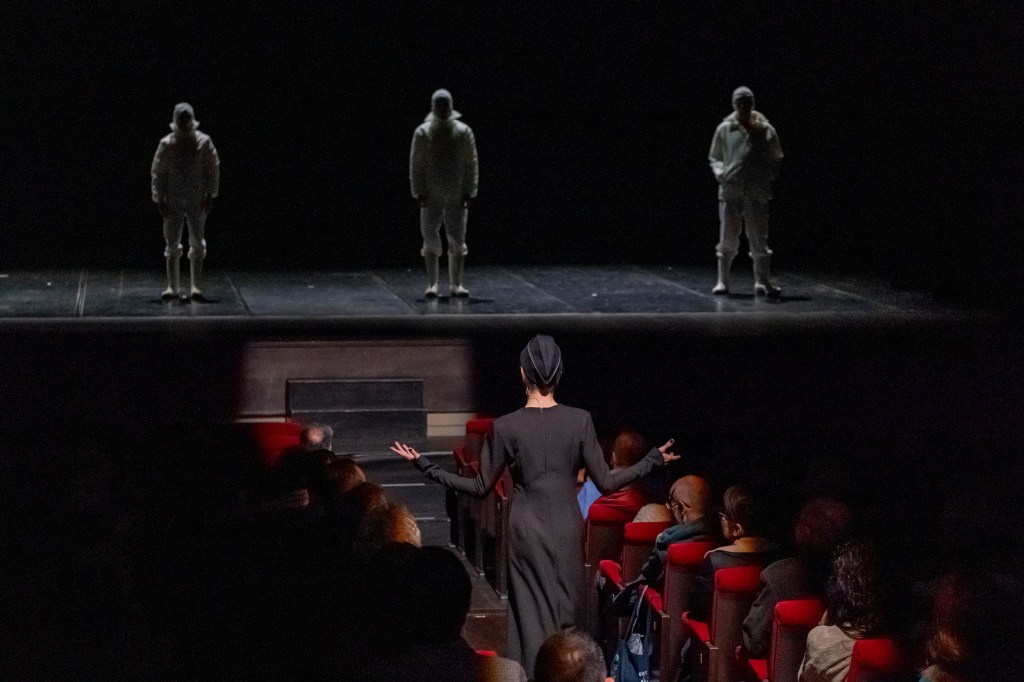

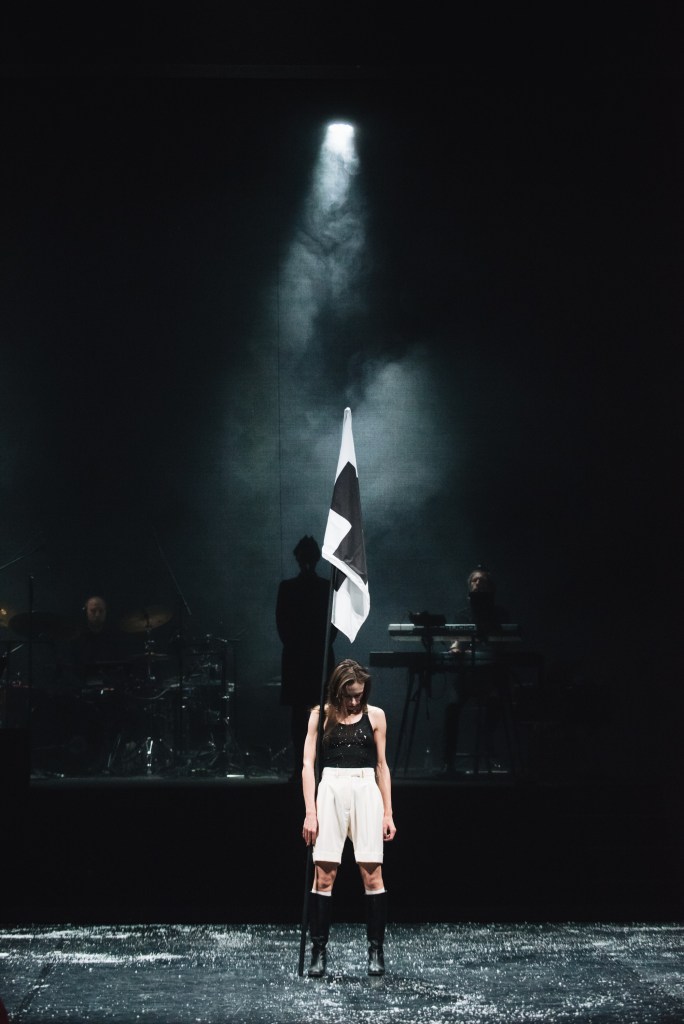

Visually, the costumes stood out as well, with striking designs like the white-clad workers, the black-uniformed Black Hats, and the red-robed Mauler.

But the ultimate question remains: how successful was this ambitious production in the end?

The first thing that stood out about the performance was how faithful it was to Brecht’s original text. Paradoxically, this dramaturgical choice might not align entirely with Brecht’s own philosophy—particularly his approach to staging canonized works and classical authors (a category he himself unquestionably belongs to). Still, there are solid reasons behind such a decision.

For one, this was the first time the play had been staged in Slovenia, so presenting it without major interventions might make sense as a way to introduce it to local audiences. Additionally, the text remains surprisingly relevant and contemporary, even after all these years. Perhaps this is why the creators of the production felt no pressing need for radical adaptation.

In fact, the timing of the premiere seemed to underscore the text’s enduring resonance: it came just days after the American elections, where modern-day “Maulers”—figures of immense wealth and power who think nothing of “stepping over dead bodies”—are not hard to spot. Yet, the play’s relevance isn’t confined to its villains. Modern “Joans” also exist—the Joan of the second part of the play, who strives for emancipation, rebellion, and the creation of a better world.

Photos by Dario Bonazza

One only needs to look at the countless feminist activists who have fought against oppression in recent decades to see this parallel. (It’s no accident that feminism comes to mind here—more on that shortly.)

Perhaps it is precisely because the performance stayed so true to Brecht’s original that the dramaturgical interventions made stand out even more. Some of these choices were undoubtedly effective. For example, Mrs. Luckerniddle was given a more prominent role, ultimately becoming a significant figure in the labor movement.

The performance also directly addressed Adorno’s well-known critique of the play. In Brecht’s original, the leaders of the strike entrust Joan with delivering a letter that contains a critical task, despite her lack of experience in trade union work. This production justified the decision by emphasizing that Joan is favored by Mauler, making her less likely to arouse suspicion—a quality that makes her particularly suited for the job.

I also appreciated the director’s choice to have Joan initially appear in the stalls—among the audience—before eventually stepping onto the stage. This decision, I believe, reinforces the idea of Joan being one of us—or, perhaps more accurately, us being one with her. This approach seems to echo Darko Suvin’s seminal interpretation of the play, where he argued that the audience should empathize with Joan and embark on a learning journey alongside her.

However, this might also be where the performance is at its weakest. It chooses to strip Joan of the naivety that defines her character in the early part of the play. In Brecht’s original text, Joan gradually comes to understand that the harsh and unforgiving world she inhabits cannot be changed with kind songs, warm soup, or religious preaching alone. She learns that cunning, defiance, and, above all, rebellion are necessary.

In this performance, however, Joan appears shrewd from the very beginning, diminishing the importance of her learning process. Perhaps this was an attempt to move away from the patriarchal trope of the “poor, naive girl” who must learn how cruel the world truly is. Yet, the execution of this idea is questionable. Joan’s cleverness in the performance is conflated with the sexualization of her body. At one point, she even tries to seduce Mauler to achieve her goals.

Does this not reflect a stereotypical male gaze—the unexamined notion that a woman can only accomplish her objectives by offering herself sexually to a man? Such an interpretation of Joan feels at odds with both a Brechtian and a feminist perspective (as mentioned earlier).

Let me end on a more positive note by highlighting two particularly successful interventions. First, casting Laibach as the Black Hats introduced the possibility of integrating songs into the performance, which aligns perfectly with Brecht’s aesthetic. At the same time, this choice added an additional interpretive layer to the Black Hats. They were portrayed as a proto-fascist group, marching fanatically and obediently to the rhythm of a higher ideal—currently religion, but soon to be fascism.

The second intervention relates to language. The performance was staged in four different languages—English, German, Italian, and Slovene. This not only enhanced the Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt but also opened up a multitude of interpretive possibilities. Two examples stand out:

First, isn’t there a subtle nod to Al Capone in the Italian-speaking Mauler, the capitalist from Chicago whose bloody business practices in the late 1920s became infamous? Second, by having characters speak in multiple languages, doesn’t the performance suggest that the exploitative conditions of capitalism are not confined to any one nation but are endemic to Western society as a whole?

This would imply that Joan’s revolutionary fight against exploitation and oppression by the wealthy elite is not just her struggle—it is, in fact, a shared battle for all of us!

(Cover photo by Daniela Neri)

Jakob Ribič is a PhD student and research group member at the Academy of Theatre, Radio, Film and Television of the University of Ljubljana (Slovenia). He is currently working on his doctoral dissertation on Bertolt Brecht.

One response to “Saint Joan in Ljubljana: A Call for Rebellion – by Jakob Ribič”

[…] Santa Giovanna a Lubiana: una chiamata alla ribellione Jakob Ribič, “E-CIBS”, 20 gennaio 2025https://e-cibs.org/2025/01/20/saint-joan-in-ljubljana-a-call-for-rebellion-by-jakob-ribic/ […]

LikeLike