To stage Brecht well is more than to perform a play—it’s to issue a political challenge.

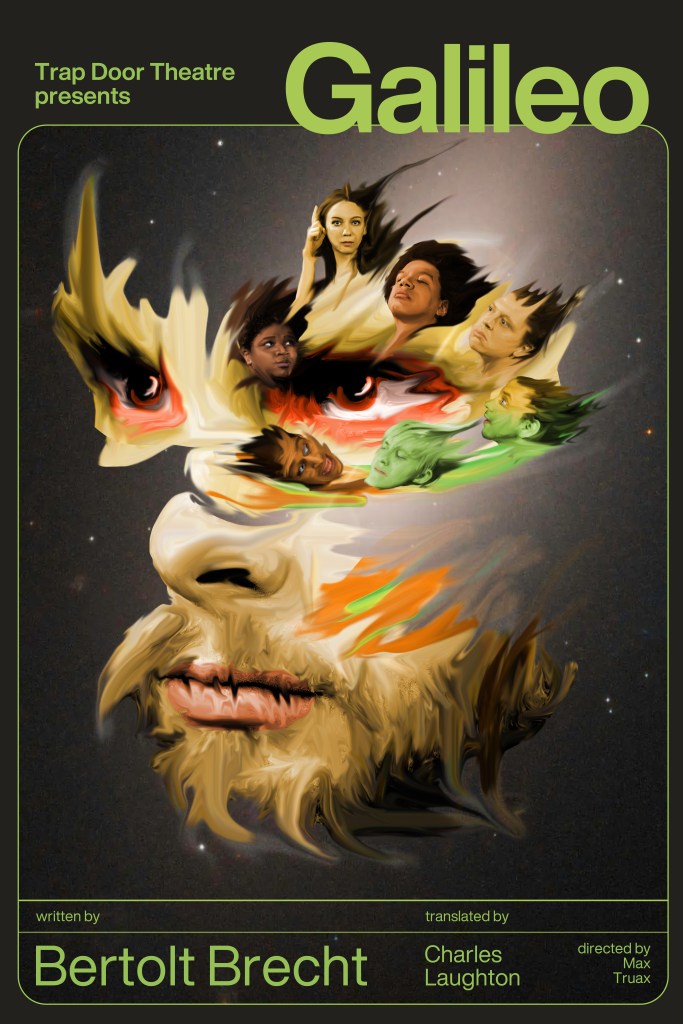

In my opinion, Life of Galileo is Brecht’s greatest work. This quasi-biographical play dramatizes the clash between science and state authority, placing Galileo’s confrontation with the Church at the center of a broader struggle: empirical observation and falsifiability versus ideological fancy and delusion. That conflict feels disturbingly familiar today. So, it’s fitting that the Trap Door Theater in Chicago would bring this play to the stage at a time when empirical reality is under siege. But to call this production merely a “staging” misses its deeper force. The entire experience—from entering the theater, to final blackout—functions as a living act of resistance, a deeply Brechtian act of social confrontation.

Trap Door Theater’s production embodies Brechtian estrangement from the moment you arrive. There is no red carpet, no marquee, no lobby. Instead, a sign directs guests down a narrow, cavernous walkway tucked between two brick commercial buildings. A metal utility door leads you not into a foyer but directly into a working restaurant kitchen. Cooks and kitchen workers bustle around you with trays and orders, navigating their workspace, laboring. The signage that brought you there assures you you’re in the right place but every norm of entering a theater, a lifetime of socialization is telling you this doesn’t seem right. This is not the front of the house. It’s not even backstage. You’re entering the building like a worker does, through the back. In these moments, you are forced to assume the role of a worker. You must walk the path a worker takes to work; you must enter the building through a service door; you are forced to emerge in their occupational space. Whether by design or chance this jarring, unfamiliar path forces you to reflect. Who usually enters here? Why are you here? The experience creates an estrangement which primes you to think about social class, access, and performance before the play even begins.

The theater space itself is modest but purposeful—a simple black box stripped of ornament with a tiny foyer where cast members double as ticket takers, concession workers, and ushers. This reinforces a spirit of collective labor creating a co-op atmosphere and a sense of solidarity that permeated the entire experience. It’s all deeply collaborative—and deeply Brechtian. This isn’t just a theater that reflects working-class values. It enacts them. It’s theater-as-praxis: a space where collective artistic labor and political purpose merge.

Furthermore, it is a theater that has a reputation for offering meaningful, socially relevant works, and Life of Galileo was no exception. David Lovejoy’s portrayal of Galileo captures more than the scientist’s genius and cheek—it embodies the stakes of truth-telling in a world where entrenched powers are bent on silencing inconvenient facts. Amber Washington brings unexpected strength and presence to Galileo’s daughter, a character often silenced in the text, turning absence into agency. Director Max Truax amplifies Brecht’s confrontational approach. This production doesn’t just retell a historical drama. It reactivates it—speaking directly to the science denial, authoritarian drift, and ideological warfare playing out in real time.

In Galileo, science is cast as a force for human progress. Ideology—represented by the Church—is exposed as a tool to conserve wealth and power. That tension continues to animate American politics today. From The Great Man and his MAGA mob’s climate change denial, to their vaccine disinformation, to censorship and sackings of scientists, to attacks on universities and public education, this suppression of science has never been about science itself—it’s about protecting unearned and unjustified privilege. Empirical reality can be dangerous to the powerful, because it can affect their pocketbooks. And so, the powerful fight back with myths, illusions, religions, and fantasies and when all else fails they turn to violence and force, just like in Galileo’s case. This is the nature of the war in which we find ourselves. And this is the war Life of Galileo dares to stage at a time when it’s urgently needed.

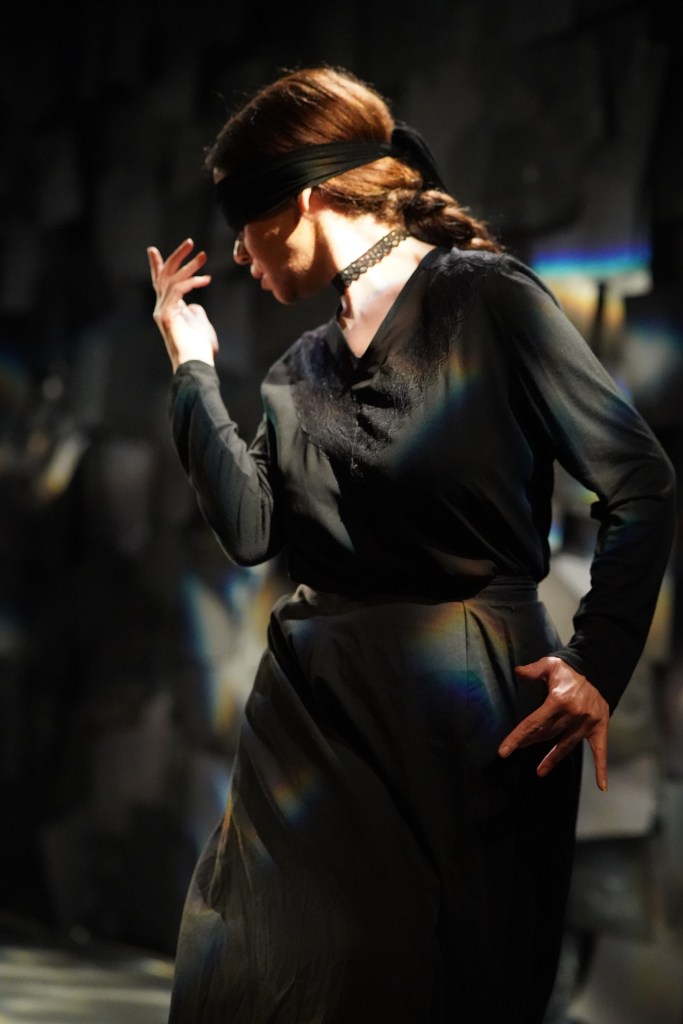

Photos by J. Michael Griggs. Upper: David Lovejoy and Amber Washington. Middle: (L) Gus Thomas and Joan Nahid; (C) David Lovejoy; (R) Dan Cobbler, David Lovejoy, Joan Nahid, and Genevieve Corkery. Lower: Dan Cobbler, David Lovejoy, and Genevieve Corkery.

Director Max Truax emphasized this urgency when I reached out to him to learn more about his vision for the piece. He told me the inspiration to produce Galileo came after Trap Door’s staging of Mother Courage and a conversation with a colleague about Brecht’s ongoing relevance. When he reread Galileo, the parallels to current attacks on science in the U.S. became clear. During rehearsals, the political climate only intensified, reinforcing the production’s purpose. Truax explained that the company used direct address deliberately—especially in moments that resonated with the current cultural moment. For example, when Andrea (Shail Modi) cries out, “They are murdering the truth!” the line was repeated multiple times, each with a different inflection to deepen its impact.

I asked Truax what he wanted audiences to take away from this production. He acknowledged the risk of political theater “preaching to the choir” in a city like Chicago. But, he said, there’s an old saying: “You preach to the choir to get them to sing louder.” His hope is that the performance galvanizes people—to speak, to act, to resist. Brecht, for him, is not just a playwright but a tool for political intervention. He noted that every Brecht play has its own vocabulary and that to treat Brecht as a museum piece is to miss the point. Just as Shakespeare shouldn’t be trapped in faux-British accents and poofy dresses, Brecht shouldn’t be trapped in grainy photos and clichés of estrangement. What worked for Mother Courage, he said, didn’t work for Galileo—so they built a new vocabulary. That flexibility, that responsiveness, is what keeps Brecht’s work alive.

Trap Door Theater found the right language. Their Galileo isn’t historical reenactment. It’s political intervention. It’s theater that demands something of its audience—not passivity, but participation. It is a model of what political theater can be: relevant, urgent, embodied. From a disorienting entrance through a kitchen to a rallying cry for shareable, objective, empirical truth, the production never lets you settle. And that’s the point. This isn’t escapist theater. It’s confrontational theater—confronting systems of power, confronting the ideological illusions that support them, and confronting us, the audience, with the question: What are you going to do about it?

Click here for the full interview with Max Traux.

Anthony Squiers, PhD, Habil. is a faculty member at AMDA College of the Performing Arts and co-editor of E-CIBS. He is the author of An Introduction to the Social and Political Philosophy of Bertolt Brecht and Bertolt Brecht’s Adaptations and Anti-capitalist Aesthetics Today.

Cover photo: Joan Nahid, David Lovejoy, and Shail Modi – Photo by J. Michael Griggs

Full Interview with Max Truax

AS: Why Life of Galileo now? Do you see any parallels between the depictions in the play and what’s going on now?

MT: Absolutely yes. When we produced Mother Courage last year, it was in the earlier stages of 2 significant conflicts that were dominating the American news cycles – Russian’s war on Ukraine and the Israel-Hamas war in Palestine. Brecht’s critique of the follies of war-profiteering was incredibly timely (though it’s probably always timely), especially considering the U.S.’s relationship with these wars and it’s long history of war profiteering.

The inspiration to produce The Life of Galileo came from a conversation about Trap Door’s production of Mother Courage with my colleague David Simmons of Fermats Theatre in Madison, WI. When our discussion turned to the relevancy of other Brecht plays, he encouraged me to revisit Galileo. Fortunately, I took his advice and reread the script. I was astounded by how incredibly relevant the piece was to what was, at that time, the current political climate in the U.S., namely a pervasive challenge to the very notion of fact and truth. The reread inspired the vision for our production and prompted me to pitch my idea to Beata (Trap Door’s Artistic Director) right away. Little did I know what our world would look like less than a year later, with an open and ongoing revolt against the very notion of science and reason led by a man interested only in building and protecting his own power.

AS: What moves (choices, techniques) have been implemented to bring those parallels to light?

MT: The current administration took control during our rehearsal process for this production. Though its actions didn’t change our vision, they did add fuel and provide us with a focus and a sense of purpose, both of which informed a lot of what you’ll see in the staging. For example, many of the moments we selected to use direct address were due to their relevance to what we’re experiencing today. One specific example: When Andrea exclaims late in the play “They are murdering the truth!” We chose to repeat this line multiple times, with each utterance keyed into a different layer of its poignancy.

AS: What would you like our readers to know about this production?

MT: Currently, producing political theatre in the U.S. so often feels like preaching to the choir, especially in a city like Chicago. I don’t expect that anyone in the audience will fundamentally disagree with the premise of Brecht’s argument or the relevancy of it to what’s happening in the U.S. But there’s an old saying that says the reason you preach to the choir is to get them to sing louder. My hope is that seeing this production will inspire people to use their voices and, when the time calls for it, to take a stand.

AS: You’ve done two Brecht plays back-to-back. Why?

MT: For me, the way Brecht uses storytelling to engage in political discourse is uniquely potent. I’m convinced that, at any given point in time and place, there’s always a Brecht play that is incredibly relevant. There are a lot of factors I could identify that contribute to what is a long-held and personal connection I have with his work. But one major factor is that the way Brecht uses allegory to deliver his discourse engenders it with a combined sense of urgency and timelessness that enables any given production to be simultaneously both a call to action and a commentary on the human condition. It’s an incredibly enticing opportunity for a theatre-maker.

This is the 5th Brecht play I’ve directed, and hopefully it won’t be the last. So I suppose it was just a matter of time before I did two of them back-to-back.

AS: Did you learn anything from the Mother Courage production that you applied to Life of Galileo?

MT: There are two things I can say working on Mother Courage taught me or perhaps reinforced for me. First, like Mother Courage, everything about the production starts with the lead. The energy, intelligence, sensitivity, and creativity that David Lovejoy brought to this production, starting with hir audition, influenced and informed everything else. David was and is the de factor leader of the ensemble and the keystone to everything in the production.

Second, every Brecht play has its own vocabulary. When studying Brecht in school, I, like most other young theatre artists, associated Brecht with a certain style of theatre conveyed by photos and snippets of film reels. I’ve seen a number of productions that attempt to recreate this style in one way or another, and it so often rings as inauthentic or, at best, like a museum piece about Brecht’s work. I’m reminded of seeing productions of Shakespeare with all the actors speaking with terrible British accents and the men in tights and the women in heavy, poofy dresses – in what is presumably an attempt to capture the playwright’s intent at the time it was written, the relevancy of the play gets completely lost. What worked for Mother Courage didn’t necessarily work for Galileo. We had to establish our own vocabulary and rules, we had to choose the appropriate moment to betray the vocabulary and to break those rules, and we had to remain true to the characters and their relationships throughout. Which is to say, we had to approach it much the same as we would any other play.

That said, Trap Door’s ethos, aesthetic, and relationship to the audience is fairly well aligned with Brecht’s vision for the theatre. It’s all about engaging and galvanizing the spontaneous community that exists for those precious 90 minutes, and hopefully getting them to sing a little louder.

Trap Door Theater’s Life of Galileo is a remarkably relevant, politically charged production that brings Brecht’s critique of ideology and defense of scientific truth into sharp focus. From its disorienting entry through a working kitchen to its modest, co-op-style performance space, the experience immerses the audience in working-class perspective. Director Max Truax and the ensemble transform the play into a living act of resistance, challenging viewers to reflect on power, truth, and the necessity of taking a stand.