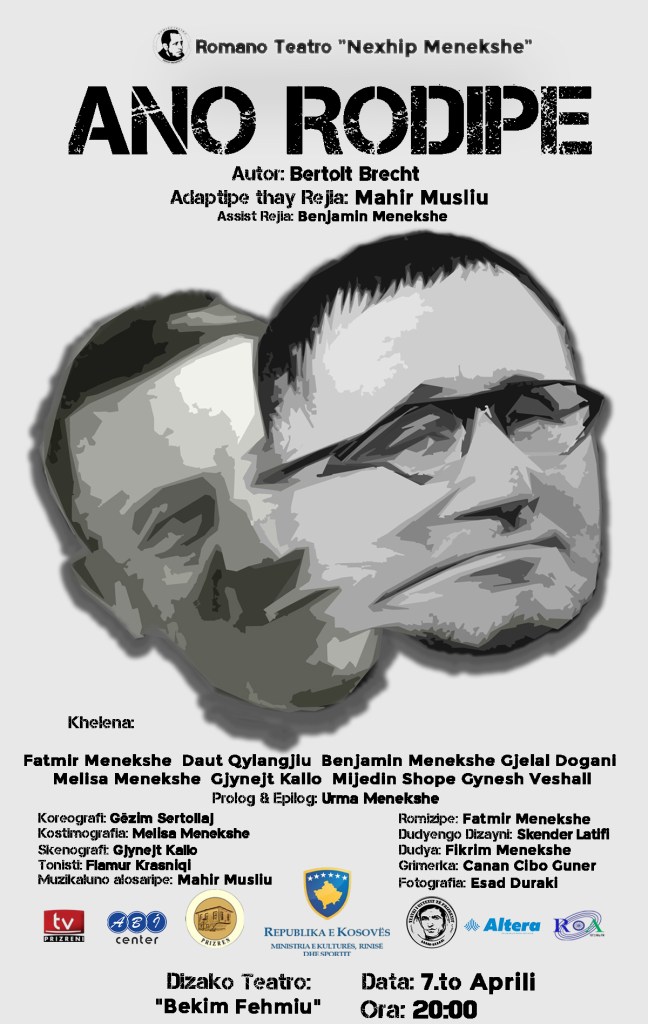

The Romano Teatro Nexhip Menekshe in Prizren, Kosovo, created Ano Rodipe (“In Search”, in Albanian: “Në Kërkim”), an adaptation of three scenes from Bertolt Brecht’s Fear and Misery of the Third Reich – “Judicial Process”, “The Physicist”, and “The Spy” – in the Roma language. The production, directed by Mahir Musliu, premiered on 7 April 2025 at the Bekim Fehmiu Cultural Centre in Prizren.

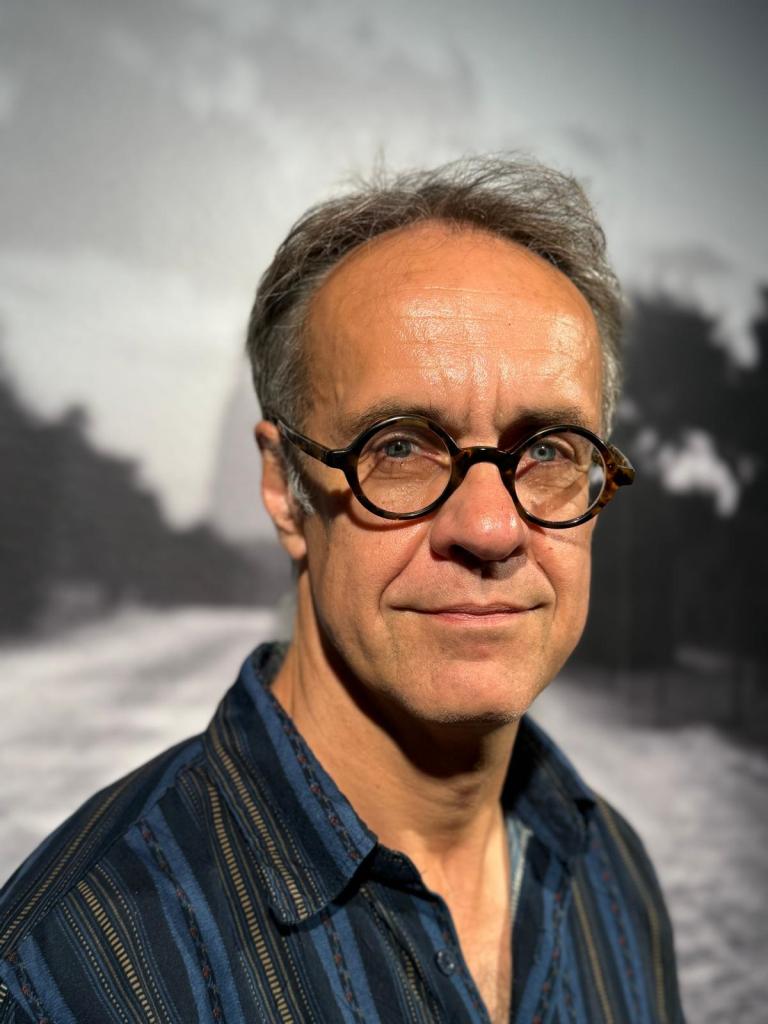

Benjamin Menekshe was assistant director for the production and acted in several roles. We met online on 26 May 2025 for an interview. The following text blends parts of the transcript of the interview with written responses by Menekshe to some of the questions.

Joerg Esleben (JE): Could you tell me a little bit about the history of the Nexhip Menekshe Romano Theater. How did it come about?

Benjamin Menekshe (BM): The Romano Teatro Nexhip Menekshe was established in 1989 as part of the NGO Durmish Aslano. It plays a vital role in preserving and developing the Romani language, identity, and culture through theatrical art. The theater is a central part of the cultural life of the Roma community in Kosovo and beyond.

JE: What are the aims and objectives of this company?

BM: The company’s goals are the promotion and protection of the Romani language; the presentation and preservation of Romani identity and culture; mass education through messages that reflect the social and historical struggles of the Roma; achieving high artistic standards and representing the community with dignity in the cultural scene.

JE: What have been the company’s major past productions?

BM: Since its founding in 1989, the Romani Theater has had a rich creative tradition, especially through the work of Romani writers and artists. One of the key figures was the late Nexhip Menekshe, a Romani playwright and director, who left behind a significant cultural legacy. He wrote twelve original plays and directed eighteen theatrical productions, all dealing with specific themes of the Romani community – including challenges in education, early marriages, discrimination, and also comedic works reflecting everyday Romani life. Following his passing, the theater was officially named in his honor. His daughter, Urma Menekshe, is currently publishing all his works in five languages: Romani, Albanian, Turkish, Serbian, and English. The first published work, Kamberi and Leyla, was released this year.

In addition to original Romani content, the theater has recently expanded its repertoire to include international works, moving beyond its traditional boundaries. Some notable recent performances include:

- Run for Your Wife and Funny Money by Ray Cooney, bringing comedic global themes to local audiences.

- A Holocaust-themed performance featuring five monologues and pantomime, staged in an archaeological museum, highlighting the Roma genocide during WWII.

- Children’s theater productions directed by professionals, aimed at educating and culturally affirming younger generations.

This diverse approach showcases the theater’s evolution—remaining rooted in Roma identity while artistically expanding its reach.

JE: Are all the plays performed in Romani language?

BM: Yes, this is what makes it a special theater. We are the first theater that performs in the Romani language to foster heritage and language promotion for the Roma community. Since 1989 to the present we have promoted the Roma community and Roma language.

JE: And can you tell me a little bit about the reasons why this was seen as desirable and as necessary? What is the context of wanting to establish a theater to promote Romani culture.

BM: I think it is really important in the Kosovo to save the language because it is the most important for the identity of a people, and the Roma community does not have so much documentation of its history. We have our oral history. And therefore, there is a real need to create more information, more documentation, and more arguments for the history of the community. It is important to show the people that they can participate in art representing the Roma culture. Because if you have culture, you have heritage, you have everything that makes a people, and that builds pride, and precisely for that the Romano Teatro creates plays for all our topics. And it promotes the language and heritage of the Roma community not just for Roma but for all, because in Prizren, in the Kosovo, there live so many other communities, like the Turkish community, Albanian, Serbian, other communities. We have a multi-ethnic community here, and therefore, when the Romano Teatro creates a performance in the Romani language, other peoples hear the Roma language, and that is really important, because when you hear the Roma language, you become interested – why do you have that particular word here, and how do you have that word in your language – and you become interested in the Roma people. Romano Teatro is proud because we create a good network in the municipality and in the Kosovo. In Prizren, we create a bit of a family with other art lovers, and that is why it is really important for the Roma community to have the Romano Teatro in the arts and culture of Prizren.

JE: Do you perform with subtitles of any sort, or solely in Romani?

BM: I’m a director, and I don’t like using subtitles in the theater. I think it breaks the magic, you know. But when we have a request from other people, when we’re going to promote the theater in other cities, like Pristina, where we don’t have so many Roma language speakers, we need to transcribe or to use subtitles in the Albanian language. In the Brecht show In Search we use more pantomime, we create more of a universal language for everybody, to understand the emotion. So we don’t use so much dialogue, in order for all people to understand the play. But when we have more dialogue, it is in the Roma language, because that is what makes our theater specific; we promote the Roma language.

The Romano Theater has the tradition to present one performance on the 7th of April. The 8th of April is International Romani Day, and our contribution to that day is that we create a performance the day before every year, with funding or without funding. It is like a family tradition, everyone in Prizren knows that on April 7th, the Romano Teatro will have a play for Romani Day. Every year we have a bigger audience, coming from the Roma, Albanian, Turkish communities. When we have funding, we go on a tour to Macedonia, because there is also a Roma community there. When a community of Roma language speakers makes a request, we organize with them to perform there, also in other countries.

JE: Who are the actors? Are they amateur actors, or are they professionals, or both?

BM: Some of the actors change every year, so we need to hold some workshops before starting rehearsals. We have a stable core of eight actors, two women and six men. We search for plays that have six to eight roles, and we hold auditions, and sometimes we find people there who love to make theater.

JE: And how does the company choose which plays to do? What’s the process of choosing a play each year?

BM: Each member must submit at least three text proposals for the next season. And after that a selection committee is formed to evaluate and recommend the best proposals. There is a transparent voting process, and the artistic director has the authority to make initial recommendations based on their experience in theater. Every year I try to read plays from around the world, and to collaborate with a professional director in Kosovo to adapt a foreign play into the Romani language. Then we start with reading rehearsals for a month, and then it goes into the mise en scène for the stage. And every year we perform the play on April 7th.

JE: So why did you choose the Brecht play Fear and Misery of the Third Reich, and why the three particular scenes that you selected from the play?

BM: The company selected this play because it powerfully reflects oppression, fear, and torture, and draws clear parallels between the Nazi regime and modern forms of discrimination faced by the Roma. The piece conveys a strong anti-discrimination message aligning with our theater’s mission to educate and raise awareness about social injustice. The specific scenes chosen for adaption in the play In Search – “In Search of Justice”, “In Search of Physics”, “In Search of the Spy” – effectively portray a life under repression and fear. These scenes were chosen to resonate with modern realities and provoke a deep reflection among the audience while remaining accessible and thematically powerful. They deal with the search for justice, with fear, with abuse of science, like the brutal experiments under the Nazis. The Albanian director, Mahir Musliu, used some dark humor in the adpatation of the Brecht drama.

JE: What was the process of translating and adapting the play?

BM: The director adapated an Albanian translation of the play for the stage. Fatmir Menekshe then translated from Albanian to Romani and we adapted it with Roma names.

JE: What were the challenges in translating and adapting the play into Romani culture?

BM: Key challenges included translating complex emotional and political language into terms understandable and meaningful within a Romani cultural context; adapting the themes in a way that remained faithful to the original while making them relevant to the Romani experience; working with amateur actors on a demanding piece with Brecht’s distinct epic structure and expectations.

JE: How would you describe the style and the aesthetics of the production?

BM: The actors delivered a sensitive, energetic, and sincere performance, forging an immediate emotional bond with the audience. The staging encouraged introspection and empathy without resorting to melodrama. The acting was naturalistic and emotion-driven. The set and costumes were minimalist but effective, reflecting the bleakness of life under totalitarianism. We used military costumes and judges’ robes like those of the 1930s, but modern costumes for the scientists.While no specific technological or musical elements were highlighted, the aesthetic simplicity supported Brecht’s epic style, where the message takes priority over visual spectacle.

JE: You used a big scale of justice as a prop.

BM: Yes, the scale played an important role, because the actors who play the judge and the prosecutor are arguing about the law but there is no justice. And so here we don’t have justice for that person in this political story. And the play shows that with some dark humor. Because it’s still the same problem today. If you are a judge or in a position of authority, you have so much power to eliminate rights and bend the law in your favour.

JE: What specific choices did director Mahir Musliu make?

BM: Director Musliu opted for a fragmented, epic structure faithful to Brecht. He emphasized emotional and psychological realism within the stylized narrative. Musliu insisted on the maintainance of stage tension and silence, creating a reflective environment. He chose to work with amateur actors, enhancing the sincerity and accessibility of the performance.

JE: What particular elements of Romani theater characterize the production?

BM: These elements generally include the use of Romani language and sensibility, engagement of local community actors, the exploration of Romani social issues such as discrimination and identity, and the preservation of oral traditions and storytelling as central to the performance style. But overall, in this production we did not add so many specifically Roma elements besides the use of the language. The focus was more on the historical and political messages of the play.

JE: Did you use any music and media technology on stage?

BM: Yes, we projected a video prologue and epilogue which show the judge dreaming in his sleep. We used the “Ride of the Valkyries” by Wagner for the more dramatic scenes with the judge. We also played this music before the start, while seating the audience, to manipulate their expecations. Because when we sit down and hear this music, we think we’ll see something more classical rather than Brecht.

JE: What role did Brecht’s concepts of epic theater play in shaping the production?

BM: The play retained an episodic structure and a distanced narrative form. Emphasis was placed on social commentary over emotional immersion. Brecht’s intention to provoke thought, not just empathy, was clearly upheld. The actors and scenes were used as tools for reflection, not mere entertainment. We had to do some preliminary work with the actors to help them understand epic theater, why we need to have a dialogue in that way, and why we need to promote the topics in the audience and convey a message of protest. At first, it is hard for people to understand, but when we go home and reflect, we start to understand. That’s, I think, the most important aspect of epic theater, of what’s happening on the stage, not to have a direct message, but to spark reflection.

JE: What current political and social issues does the production address?

BM: It addresses discrimination against Roma people, fear and repression imposed by authority, propaganda and manipulation, and the importance of preserving identity under systemic marginalization.

JE: What were the audiences’ and critics’ responses to the show?

BM: According to director Musliu, the silent focus of the audience during the performance was a strong indicator of success. The actors described the experience as challenging but fulfilling, and the show was seen as artistically and emotionally impactful, validating months of preparation and dedication.

JE: Did you get any direct commentary from the audience?

BM: I had many conversations with people who saw the performance, and the first thing everybody liked were the actors. Because here we change the roles for the three scenes. For example, in the first scene, I was the judge, in the second, I was a physicist, and in the third scene I was the father. When you change three roles in one play, it is really difficult, you need to have a specific performance for every character. Audience members also talked about their challenge to understand why, in the Nazi times, there were these problems, with that powerful judge. And it was a little difficult to understand the Bertolt Brecht style. I think we need to read so much about other styles, like Stanislavsky, Grotowski, in order to better understand the Brecht style. But in the end, we had a very good conversation with everybody. We worked a lot on that play, we rehearsed without a specific time limit, starting at eight in the evening and ending at midnight. And the director had many ideas to improve it, to find the perfect characters. It was hard at first, but step by step, you make more and more improvements, and you grow towards performing. And then you get positive feedback, that there is no difference between the professional theater and amateur theater. I felt honored when I heard that.

There are many stereotypes about the Roma community. It is quite hard to remove them, but we need to work every day to remove them, to have a normal life. And so it is important in the theater to represent these topics and to have this message not just for the Roma community, but also for the Albanian, Turkish, and other communities, and to bring each other to have a conversation, to think about ‘who is the bad one here’? This is what happened here [in “In Search of Justice”]: the judge is in a higher position, but he does not make a good choice for justice. So between the normal people and people in higher positions, who is the problem here? And the theater offers the chance of connecting those in higher positions with normal people, they have a conversation and can find one language.

JE: Why do you feel the production is current? What current issues is it commenting on?

BM: We perform the everyday positive and negative sides for the Roma community. We engage in education and resistance. The Roma community experiences discrimination at school, at work, and we need to resist and stand up for what we are, honor what we are. That is really important if you want to overcome discrimination and other problems. We create theater on these topics – not just discrimination, but topics like the history of science, the Holocaust, and current problems – we tell the audience what an important role we play in history. Seeing what was bad before, you have the choice to be stronger now. That’s the metaphor we create in that situation – the bad situation makes you stronger for the future.

That is really important to strengthen the Roma community. If in my school or in my street, I am in a situation of discrimination, I think of the positive side of being in the Roma community, a really nice tradition. The negative thinking of the other people doesn’t matter to me. And for that, the theater is really important, because it gives the Roma community a heart, a platform where they can see theater in the Roma language. It is good to have that feeling, that I have my language and my thought. The older Romani population does tend to focus a little bit more on the negatives and the historical oppression, and what we in the theater are trying to do is to show the positivity and the opportunity and shed a future-forward light on the Romani community. I also make documentaries about the Roma community, and I try to show the positive sides, because the negative sides produce negative feelings, and I try to make transparent original Roma heritage. And that is really important for the Roma community, and also for other communities, to see the Roma in their originality. That’s going to be more powerful and allow you to love yourself, and that’s really important in the present day.

JE: Are there any further plans with the production? Are you touring? Are you going to festivals?

BM: For now, we’ll go to Pristina and play for Albanian audiences. If they want subtitles, I will create them, even though I don’t like them, as you know. After that, we would like to go to Germany. A year ago, we were in Germany with a performance of Funny Money in Munich. We need help to network in Germany and to find theatrical locations, the props, the lights, the support, everything involving the theater. We also have collaborations with our Roma community here, we go into the schools to perform. This is difficult, because we don’t have proper lighting here, we have nothing to produce a professional performance. This is also where we need help. Munich and Essen, for example, have large Roma communities. We need to find people who can help us reserve theaters, find funding, communicate in German. Most importantly, we need to network to help each other.

Information sources:

- The official web page of the Romano Teatro Nexhip Menekshe: https://radioromanoavazo.com/category/romano-teatro/

- The troupe’s Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/romanoteatronm

- Entry on the troupe in the database Roma Heroes: https://romaheroes.org/troupes/nexhip-menekshe/

- Foto essay on the troupe: Hoxha, Majlinda. “In the Roma Theater.” Kosovo 2.0, 8 April 2024, https://kosovotwopointzero.com/en/in-the-roma-theater/.

Benjamin Menekshe is a Roma activist, film director, and writer. He is a key member of the Romano Teatro Nexhip Menekshe in his roles as director, dramaturge, actor, and multimedia specialist.

Joerg Esleben is co-editor of ECIBS. He is an Associate Professor of German, Intercultural Studies, and Theatre at the University of Ottawa, Canada. His publications include Fritz Bennewitz in India: Intercultural Theatre with Brecht and Shakespeare (U of Toronto Press, 2016) and the online resource Brecht in/ au Canada.