From 26 July to 12 October 2025, the Museum Moderner Kunst (MMK), Passau presents Otto Dix. Aus der ZF Kulturstiftung.

This exhibition shows around 85 works on paper and one painting by Dix from the collection of the Kulturstiftung der ZF Passau GmbH. Spanning the years 1917 to 1969, the selection offers rare insights into Dix’s diverse oeuvre, particularly through prints seldom seen by the public. Taken together, these works reveal Dix as both a witness to history and a prophet of social collapse. His career, as the curator Anna Wagner’s comments trace, spans the brutal lessons of the trenches of World War I, biting social critiques of the 1920s, threats under fascism, and religiously inflected meditations on death and redemption that dominate his late work. Together, the works show an artist whose realism strips away every distraction to jump directly into the heart of the matter.

The First World War was a sort of crucible for Dix. As a volunteer, he endured nearly the entire conflict, fighting on both fronts, an experience that gave rise to his war etchings. In them, he negates any trace of sentimentality, instead showing mud, rats, mutilated bodies, and shattered landscapes. As the exhibition makes clear, Dix’s war art is not only a record of violence but an anatomy of humanity under extreme pressure. Few artists have confronted the dehumanizing horrors of war with such exactness and refusal to console.

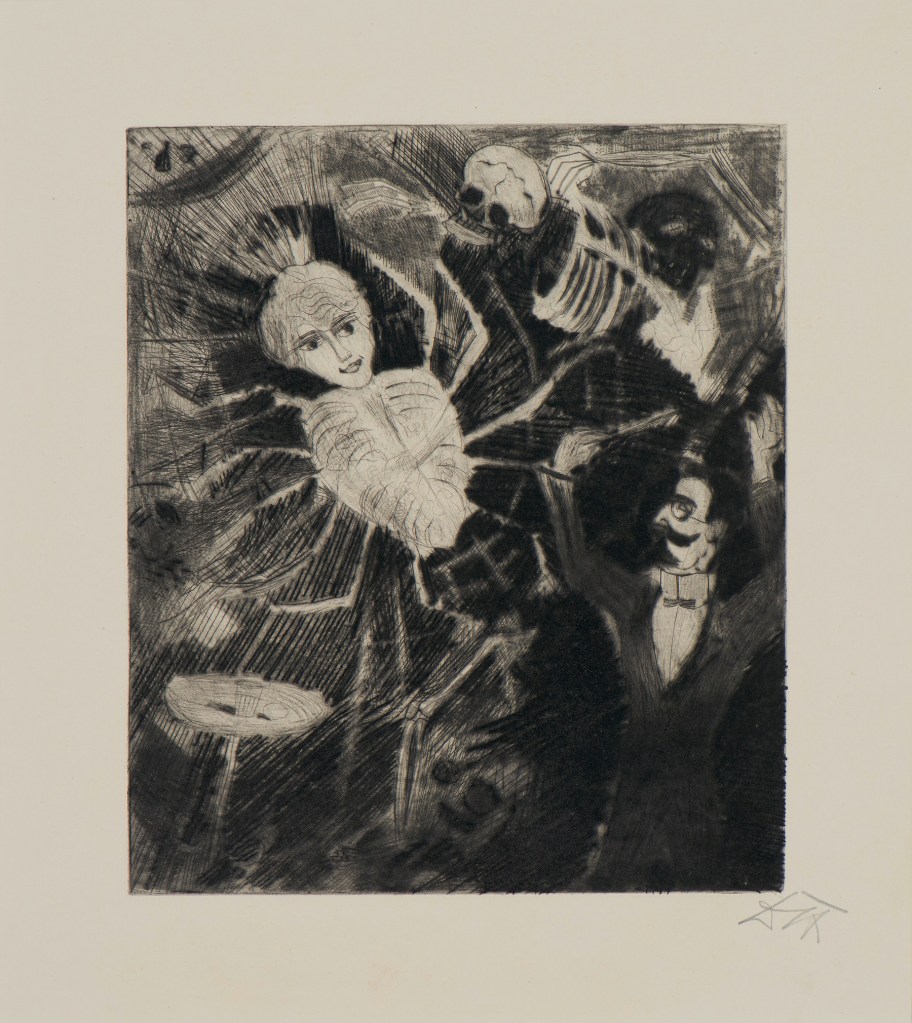

The 1920s in Düsseldorf and Dresden offered a different battlefield for Dix to portray, modern society itself. Dix absorbed the pulse of the cities and turned to its margins: prostitutes, drunken sailors, wounded veterans, criminals. With a caricatural sharpness, he exposed the decay and social wounds of Weimar life, earning recognition as a central figure of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement. Yet even in satire, he never flinched from truth. Works like the painting Vanitas (1932), with its juxtaposition of youthful sensuality and grotesque, shadowy decay, show him engaging in dialogue with the old masters like his compatriot Albrecht Dürer while forcing viewers to confront mortality head-on.

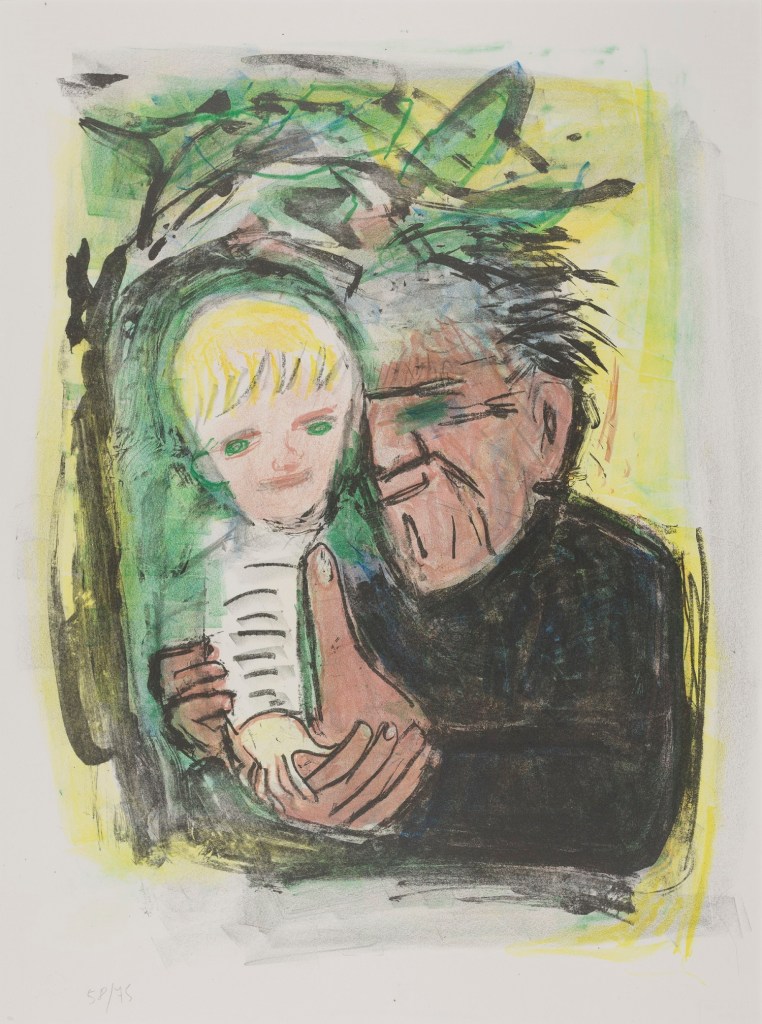

The Nazi seizure of power in 1933 marked a rupture for the artist. Stripped of his Dresden professorship and branded a creator of “degenerate art,” Dix retreated with his family to Lake Constance. In his own words, he “was banished into the landscape,” and there, painted landscapes. This testifies to both resignation and endurance. Yet even during the Nazi threat, allegories surfaced. Dix’s The Jewish Cemetery at Randegg (1935), for example, carried symbolic resonance as persecution intensified. His intimate portraits from this period, such as those of his mother and his wife, reveal another side: the Dix who could look at family life with as much intensity and insight as he once turned on the battlefield. The tender image of his baby daughter Nelly, for example, stands as counterweight to the brutality of his earlier subjects.

After the Second World War, death and redemption took center stage. Works from the late 1940s and 1950s, filled with biblical themes and images of Christ, show Dix wrestling with devastation, guilt, and the possibility of renewal. Yet, as the exhibition rightly suggests, redemption remains fragile. There is no easy grace here. Instead, the religious imagery intensifies his long-standing concern with mortality. Alongside this, children reappear in abundance, their presence signaling both the vulnerability and persistence of life. So, too, do farm animals: roosters, cows, and barnyard cats rendered with his characteristic acuity. These works suggest that Dix found resilience in the stubborn mundanity of day-to-day life.

The exhibition is rounded out with his late portraits and self-portraits, where continuity and change wrestle in every piece. Works like Ecce Homo (1968) and Self as Skull confront the reality of death directly. In the latter, Dix places himself under the same relentless gaze he had once turned on society, peeling back even his own features to the bone in search of the essence.

What emerges across these rooms is not a linear career but a set of variations on a single theme: how to look at the harsh realities of life without turning away. From visceral war etchings to intimate family portraits, from landscapes painted in forced retreat to the biblical allegories of his later years, Dix’s work insists on facing crisis as the defining condition of modernity. His roosters and children of the 1950s, no less than the corpses of the 1920s, belong to the same continuum: the persistence of life against catastrophe. This exhibition shows Dix at once at his most human and his most unsettling. His art refuses comfort, offering instead a kind of realism that confronts viewers with the truth of collapse while pointing, however faintly, to the endurance that survives it.

Anthony Squiers, PhD, Habil. is a faculty member at AMDA College of the Performing Arts and co-editor of E-CIBS. He is the author of An Introduction to the Social and Political Philosophy of Bertolt Brecht and Bertolt Brecht’s Adaptations and Anti-capitalist Aesthetics Today.

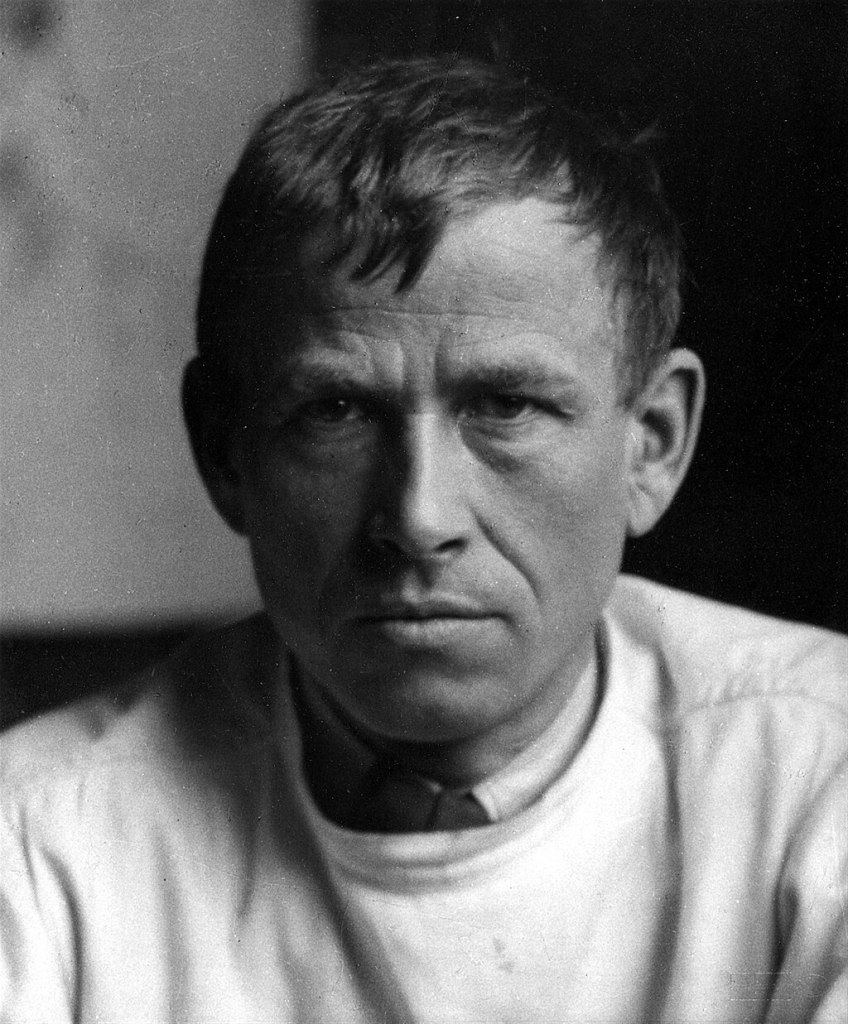

Cover photo: Otto Dix, Selbstporträt IV, Lithografie, 1957, Sammlung der Kulturstiftung der ZF Passau GmbH © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025.