La influencia de Brecht puede verse en los teatros de todo el mundo, incluida América Latina, una región que no siempre ha recibido la atención que merece en los debates sobre teatro épico y emancipatorio. Para profundizar en este panorama, el coeditor de E-CIBS, Anthony Squiers, realizó una entrevista por correo electrónico con Laura Brauer, una directora, docente e investigadora lúcida y enérgica, cuyo trabajo está profundamente ligado a la transformación social. En este intercambio, Brauer reflexiona sobre el estado actual del teatro épico en América Latina, explora los vínculos entre el teatro brechtiano y el teatro comunitario, y analiza el cruce entre el enfoque dialéctico de Brecht y el Teatro del Oprimido de Augusto Boal. El resultado es una mirada situada y viva sobre el teatro épico en la actualidad.

¿Podrías contarnos brevemente sobre tu trayectoria y cómo llegaste al teatro?

Mi identidad se formó en el cruce entre Alemania y Argentina a partir de la historia de exilio de mi abuelo al sur del mundo y los muchos años que mis padres vivieron en Alemania, impedidos de regresar por el contexto político argentino. Aunque nací en Argentina, la cultura alemana estuvo siempre presente en mi infancia y adolescencia: en mi formación en una escuela bilingüe y en las estancias que pasé en Alemania a los ocho y a los dieciséis años. Desde muy joven afirmaba querer dedicarme al teatro y querer cambiar el mundo. Cuando –años más tarde– en la carrera de actuación y profesorado de teatro en Buenos Aires conocí el teatro de Brecht, sentí una fascinación inmediata. En esta propuesta confluían mis dos grandes sueños. Era desde acá que yo quería realizar mis tentativas de contribuir a la sociedad. Recordé entonces que en mi casa había un volumen en alemán de las obras completas de Brecht que pertenecía a mi abuelo, quien incluso había tenido la oportunidad de ver ese teatro en su época, dado que provenía de Berlín. Empecé a leer las obras y los comentarios en alemán, y descubrí que el acceso que teníamos en Argentina era muy limitado: había pocos materiales en español en comparación con la enorme cantidad de escritos disponibles, y las traducciones existentes no permitían captar lo esencial de su propuesta.

Ahí fue que decidí viajar a Alemania para estudiar teatro épico y traer a Argentina los aspectos menos conocidos de la propuesta brechtiana, con un interés especialmente centrado en la actuación, que era lo que más me apasionaba entonces. Quería entender cómo se actuaba este teatro, cómo funcionaba este método, algo que en Argentina no lograba encontrar, pese a múltiples intentos.

Cuando terminé la carrera en 2005, comencé a buscar oportunidades de beca para estudiar en Berlín. Tuve la oportunidad de acceder a una primera, que me permitió realizar una pasantía en la Hochschule für Schauspielkunst Ernst Busch. A partir de esa experiencia inicial entré en un círculo virtuoso de estipendios —entre ellos, la beca de la Academia de Arte de Berlín y la del Internationales Theater Institut (ITI)— que me permitió estudiar durante muchos meses por años en Alemania (entre 2005 y 2018). Durante ese período asistí intensivamente al Archivo B. Brecht, al Berliner Ensemble y profundicé en esta línea de investigación y práctica teatral junto a personas directamente vinculadas a esta tradición. A su vez, en mi tiempo de investigación allí, conocí la existencia de Augusto Boal y el Teatro del Oprimido y comencé a estudiarlo paralelamente. Por muchos años mi práctica estuvo vinculada casi exclusivamente a estas dos propuestas teatrales.

¿Dónde estás radicada en este momento y cómo influye ese entorno en tu práctica teatral?

Actualmente estoy radicada en Buenos Aires, mi ciudad de origen, después de haber vivido nueve años en San Pablo (Brasil) y de mis experiencias previas en Alemania. La práctica teatral local influye profundamente en mi trabajo, sobre todo porque aquí existe el llamado Teatro Comunitario, un fenómeno local con más de cuarenta años de trayectoria. Fue desarrollado en este formato por el grupo Catalina Sur, dirigido por Adhemar Bianchi, quien junto con Ricardo Talento impulsó la Red de Teatro Comunitario y se dedicó a entusiasmar a personas de distintos barrios a involucrarse en esta forma teatral.

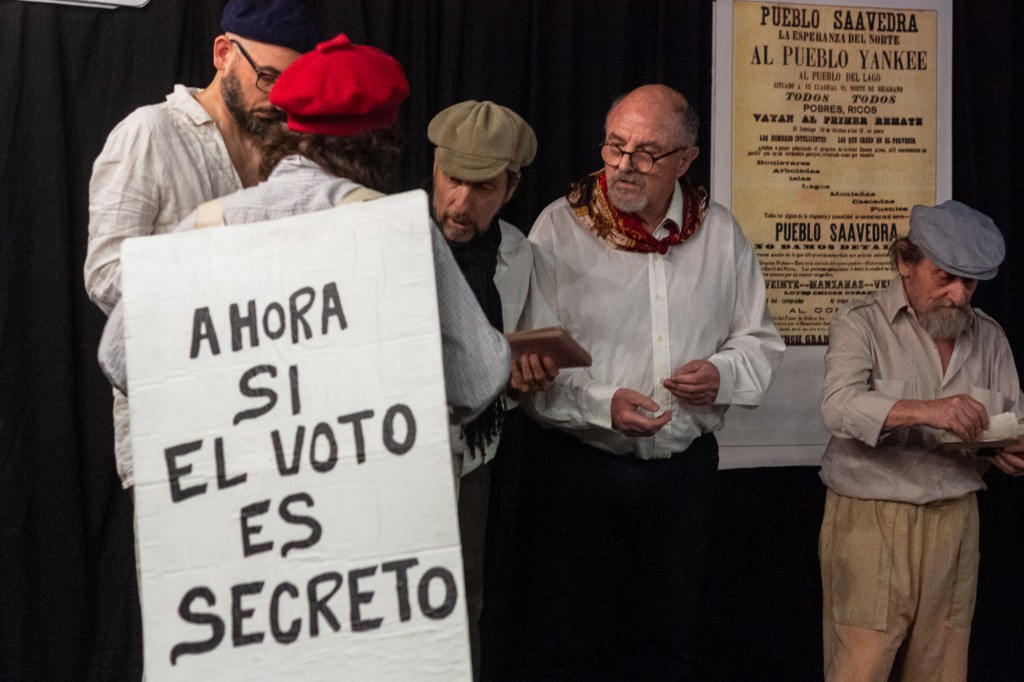

El teatro comunitario consiste, fundamentalmente, en una propuesta vinculada al territorio y a la memoria colectiva. Convoca a vecinas y vecinos —personas sin formación profesional artística— a crear una obra dirigida por profesionales, con un fuerte componente musical y con la intención de narrar la historia del propio barrio. Estos elencos, que se han multiplicado a lo largo de las décadas y que hoy superan los sesenta en todo el país, realizan un teatro vivo, popular y comprometido con los asuntos públicos. No buscan, como el drama tradicional, la verosimilitud, el ilusionismo ni la exposición de historias privadas; más bien proponen un lenguaje escénico abierto, popular, exterior, y realizado con frecuencia en espacios públicos. Se trata además de un movimiento de gran magnitud: los grupos reúnen desde veinticinco hasta doscientos integrantes en escena y emplean técnicas híbridas. Incorporan títeres, muñecos, carteles narrativos y una enorme libertad creativa para representar hechos históricos. El relato se organiza alrededor de un objetivo político-social concreto, siempre desde un marcado énfasis en el sujeto colectivo, por sobre el sujeto individual.

Estoy mencionando tan fuertemente al teatro comunitario, porque lo considero un tipo de teatro perteneciente a la línea histórica en la cual se inscribe también el teatro de Brecht, es decir, como un tipo de teatro épico. Encontré en esta práctica teatral una propuesta que me convocó inmediatamente y que considero mucho más interesante que la puesta en escena que puede haber en esta ciudad de dramaturgias del propio Brecht o cualquier otra manifestación del aparato teatral convencional.

Realizo actualmente una investigación en la que sostengo que el teatro comunitario es un tipo local de teatro épico. En esta investigación procuro ampliar la noción de lo “épico”, para que deje de ser pensada como sinónimo de “brechtiano” y pueda ser utilizada como categoría de análisis, en contraposición con el género lírico y el dramático. Lo específico de la propuesta de Brecht sería la dialéctica, pero lo épico, tal como él mismo afirmaba, excede su propia propuesta.

Desde que volví a Argentina hace tres años, impulsada por Ricardo Talento, dirijo mi propio grupo en el barrio donde vivo actualmente, llamado: Saavedra. Mi práctica teatral principal está totalmente vinculada a la experiencia local. Pertenecemos a una red nacional y nos inscribimos dentro de este tipo de teatro local. Cada grupo mantiene plena autonomía estética, y mi grupo, sin dudas, tiene mucho del tipo de teatro que me interesa y con el que me formé (no sólo en Argentina), pero es muy abierto y se retroalimenta constantemente de las propuestas del equipo de trabajo, de los otros grupos y de los y las participantes.

Has trabajado extensamente con textos de Brecht e impartes clases sobre sus métodos. ¿Podrías delinear cómo ha sido tu recorrido con su obra?

Creo que hay algo muy interesante que nos ocurre a quienes estudiamos insistentemente la propuesta de Brecht y queremos llevarla adelante de forma práctica: el recorrido termina siendo muy artesanal. El inicio —aquellas primeras veces que di clase, al regresar de mi primera experiencia de investigación y de la pasantía en la escuela alemana de teatro— casi no tiene nada que ver con lo que hago actualmente. Al principio hubo mucha búsqueda específica acerca de cómo hacer visibles para un público local, argentino, ciertas referencias que para los alemanes son absolutamente naturales. El teatro alemán, incluso aquel que no está vinculado a Brecht, tiene un abordaje exterior, narrativo, fuertemente épico y las referencias resultan muy evidentes para ellos.

Luego, durante mis años de estadía en Brasil, conocí una forma de aproximación al teatro también muy distinta de la argentina y el diálogo pedagógico varió. Hizo falta trabajar desde otras estrategias. Por eso, mi recorrido desde 2006 hasta hoy ha cambiado mucho, no sólo por la incorporación de nuevos conocimientos, sino también porque el aula fue un espacio de gran experimentación, y en ese proceso fueron cambiando los modos de abordar el trabajo, de comprender lo que era eficaz. En este camino hubo mucha invención de ejercicios y mucho trabajo a partir de los textos, algo que me resultó fundamental conocer del trabajo metodológico en la pasantía en Alemania. También trabajamos intensamente sobre temáticas sociales de interés, siempre a partir de un eje fuerte: para qué lo hacemos y para quién. Esas preguntas son el principio organizador de toda la propuesta escénica.

¿Podrías compartir alguna experiencia significativa de trabajo con alguno de sus textos que haya marcado tu manera de concebir el teatro épico?

Una experiencia muy significativa en mi recorrido fue una puesta en escena que realizamos en la periferia de São Paulo. Trabajo con mucha frecuencia el texto “La excepción y la regla” de Brecht y, en esa ocasión, junto con un grupo de estudiantes, realizamos dos puestas en escena distintas del mismo texto. El objetivo era mostrar cómo, aun trabajando con el mismo propósito político y dirigiéndose al mismo público, es posible representar un mismo material de maneras diferentes. Cada grupo eligió estrategias narrativas propias. Así se volvían evidentes las distintas formas de representación posibles y funcionaba pedagógicamente para verificar cómo dialogaba cada estrategia frente al público.

La experiencia fue especialmente enriquecedora porque se trataba del último año del proceso de formación actoral en la Escola Livre de Teatro de Santo André. Presentamos la obra en el Movimiento Sin Tierra (MST), donde tuvimos luego una conversación especialmente profunda. Más tarde llevamos la propuesta a otro espacio, donde el público estaba compuesto por trabajadores y trabajadoras de una imprenta. Muchos de esos jóvenes nunca habían tenido contacto con una obra de teatro, y eso volvió la experiencia aún más interesante. Lo fundamental fue que, a partir de la representación, reconocieron en la obra aspectos de su propia vida laboral. Las discusiones que surgieron después estaban directamente relacionadas con sus condiciones de trabajo, y ese reconocimiento los llevó incluso a tomar decisiones vinculadas a la organización colectiva frente a sus jefes. Esa experiencia fue una de las más importantes de mi trayectoria, porque permitió confirmar que este tipo de propuesta teatral, realmente consigue traer —de un modo distinto al habitual— temas que forman parte de la vida en sociedad de ese público. Y, lo más relevante, demuestra que puede ser una herramienta útil para hacer avanzar la lucha.

¿Qué aspectos de sus obras y teorías te resultan más fértiles para la escena contemporánea?

Creo que lo más interesante de la propuesta de Brecht es su deseo de transformarlo todo dentro del teatro, para que el teatro mismo pueda cumplir una función social distinta: contribuir a la transformación de la sociedad desde una perspectiva en la que las personas podamos tratarnos como amigas y vernos como iguales. En ese sentido, su dramaturgia, aunque resulta fascinante, está excelentemente escrita y sigue siendo vigente en muchos aspectos, ciertamente también resulta propia de otro tiempo.

El mundo ha cambiado, y esos cambios exigen adaptaciones y actualizaciones para que los textos dialoguen directamente con nuestras problemáticas actuales. Por eso considero que lo más valioso de la propuesta brechtiana tiene dos dimensiones. Por un lado, su impulso transformador del propio teatro, que rompe con convenciones establecidas y obliga a crear nuevas formas de representación. Por otro lado, la idea de que las obras deben estar orientadas a provocar un diálogo profundo con la sociedad, de manera tal que el público pueda reconocerse en el mapa social y descubrir desde qué ángulo actuar para contribuir al cambio y lograr un mundo más justo, igualitario, solidario y, en fin, mejor para todas las personas.

En tu experiencia, ¿cómo se ha reinterpretado el legado de Brecht en América Latina? ¿Qué particularidades adquiere el teatro épico cuando se cruza con las realidades sociales latinoamericanas?

Creo que la realidad en América Latina es muy diversa y cambia mucho según el país. En lugares como Colombia y Brasil existieron personas que fueron al Berliner Ensemble de Brecht y trajeron a sus respectivos países estas referencias a sus contextos locales. A partir de ello se generó una línea de trabajo basada en este teatro, pero apropiada de manera específica, con una profundidad difícil de comparar con la de países donde esa mediación no ocurrió, como Argentina o Uruguay. En estos últimos, Brecht fue interpretado principalmente a partir de sus textos, lo que implicó trabajar con una teoría sin una referencia práctica. Por eso, en esos países suele encontrarse un Brecht más duro, solemne, menos entendido, a pesar de ser un autor de estudio y puesta fundamental.

En São Paulo, en cambio —y esto me lo dijeron incluso en Berlín— parece haberse consolidado una suerte de “capital brechtiana” en el mundo, por la cantidad de grupos que se declaran así y por el vínculo con un tipo de teatro profundamente conectado con los intereses sociales. En esa misma línea se inscribe también la propuesta de Augusto Boal y el Teatro del Oprimido. Encontré en São Paulo una serie de apropiaciones del legado de Brecht muy ricas, muy situadas y profundamente pertinentes para dialogar con esa sociedad.

A diferencia de lo que pude observar en Alemania, creo que en América Latina se sostiene aún un enfoque ligado al punto de vista ideológico en torno a Brecht. En Alemania, en cambio, encontré una posición muy asociada a la idea de que vivimos en un momento donde la perspectiva brechtiana sobre el mundo sería algo pasado, y donde lo contemporáneo ya no podría pensarse en términos ideológicos como en la época en que Brecht escribió. Ese desplazamiento hace que su legado se concentre allí principalmente en aspectos formales: la fragmentación narrativa, la dramaturgia episódica.

En cambio, en América Latina —hasta donde entiendo— se mantiene un interés fuerte en Brecht ligado a su mirada crítica del mundo, a su invitación a reflexionar sobre las condiciones sociales y a su deseo de transformación. Esa es, quizá, la diferencia más significativa.

¿Consideras que hay hoy en el continente una nueva generación de creadores que retoma o transforma la herencia brechtiana?

Como decía anteriormente, existen propuestas teatrales que podríamos llamar modalidades de teatro épico, aunque no sean estrictamente brechtianas porque no conservan la dialéctica como eje central. Sin embargo, se inscriben en la misma tradición histórica a la que perteneció el teatro de Brecht: una tradición que busca intervenir en la sociedad y contribuir a su transformación. En Brasil, por ejemplo, encontramos una referencia fundamental en el Teatro del Oprimido, que puede pensarse como una forma local de teatro épico. En Argentina, del mismo modo, el teatro comunitario utiliza dispositivos escénicos donde lo colectivo y lo social se convierten en materia teatral y entran en esta tradición.

En cambio, si tengo que pensar estrictamente en el material textual de Brecht, las puestas en escena de obras de él realizadas en teatros tradicionales dentro del aparato teatral, me resultan muy poco vinculadas al interés original. Muchas de ellas parecen hechas por personas que no son especialistas en el tema o que desconocen realmente de qué se trata el teatro brechtiano. Como consecuencia, suelen repetir un estilo cercano al que se difundió en los últimos años de vida de Brecht y sus puestas del Berliner Ensemble, usando técnicas y formas como fórmulas desligadas de su sentido, lo que —a mi entender— no es lo más interesante ni lo más fértil de su legado para nuestra realidad.

Estudiaste directamente con Boal en Brasil. ¿Qué te dejó esa experiencia en términos metodológicos y humanos?

La experiencia de estudio con Augusto Boal fue un verdadero divisor de aguas, un antes y un después en mi vida. Fue una enorme fortuna haber podido conocer a ese gran maestro que, más allá de lo técnico y lo metodológico, enseñaba cómo enseñar y, en definitiva, cómo estar en el mundo. Era una persona de una generosidad y una humildad extraordinarias, profundamente accesible.

Aprendí muchísimo porque el seminario estaba dirigido a multiplicadores, es decir, a personas que ya veníamos con ciertas experiencias prácticas, aunque muchas veces desarrolladas intuitivamente, a partir de lecturas, de referencias y de lo que habíamos visto en otras partes, principalmente en Europa. Poder realizar prácticas guiadas por el propio creador del método, al mismo tiempo que formular preguntas directamente relacionadas con nuestras experiencias concretas, fue algo inmensamente enriquecedor. Esa instancia transformó de manera radical la forma en que encaramos el trabajo a partir de entonces.

En ese momento yo coordinaba un grupo, llamado Actuarnos Otros y ya hacíamos Teatro del Oprimido desde hacía un tiempo. Sin embargo, la experiencia con Boal permitió un cambio profundo en la construcción del material posterior. En lo personal, me brindó un entendimiento mucho más nítido y contundente de lo que realmente significa esta práctica.

¿Cómo dialogan, en tu práctica, las ideas de Boal con las de Brecht? ¿Encuentras tensiones o complementariedades entre ambas poéticas?

Creo que se trata de dos propuestas muy diferentes. La propuesta de Brecht posee un grado de sofisticación mucho mayor, según la entiendo. La propuesta de Augusto Boal, al ser más sencilla en su estructura, es también más fácil de llevar a la práctica, y por ese motivo funciona, tal como él decía, como una verdadera caja de herramientas adaptable a cualquier contexto. La propuesta brechtiana, en cambio, no funciona así. Es mucho más difícil de condensar y exige un estudio permanente. Requiere comprender el funcionamiento de la dialéctica, algo que no es sencillo. Quienes estudiamos el teatro de Brecht sabemos que es un estudio que no acaba. El Teatro del Oprimido, por otro lado, tiene las limitaciones propias de todo aquello que busca ser accesible y aplicable de forma inmediata. Y es fundamental que existan propuestas de este tipo. Justamente porque quiere ser una herramienta, pierde ciertas capas de complejidad que sí están presentes en Brecht. Por eso, ambos caminos son muy distintos, aunque compartan un interés común: contribuir a la transformación social mediante el lenguaje teatral.

En tus trabajos con comunidades y en contextos no convencionales —como cárceles o escuelas—, ¿cómo se integran estas influencias?

Colectivo Saavedrepico en parque Saavedra 2025.

En contextos no convencionales he trabajado bastante combinando ambas propuestas. Suelo empezar con el Teatro del Oprimido, porque tiene ejercicios y juegos muy dinámicos, accesibles y pensados para personas sin experiencia teatral. Después de trabajar específicamente con la técnica del teatro-imagen, analizando situaciones y discutiendo lo que aparece conceptualmente, paso a una segunda etapa en la que introduzco la lectura de una obra o un poema de Brecht. A partir de ese material, trabajamos libremente cómo ponerlo en escena. No seguimos el texto al pie de la letra, pero sí respetamos las contradicciones que presenta. Esta forma de trabajo siempre funcionó bien: se llegaron a propuestas escénicas relevantes para las personas participantes, partiendo de un texto brechtiano como disparador. La combinación resulta eficaz, porque permite primero aproximarse de manera sencilla y colectiva a temas complejos, y después, a través de la lectura de Brecht, abrir otra camada de lectura, en la cual surgen nuevas preguntas e ideas.

Tu nuevo libro, Brecht en la práctica—“una exploración clara, práctica y dialéctica del teatro brechtiano, enfocada en analizar, crear y transformar la realidad mediante la escena”—, ¿qué puedes decirnos sobre él? ¿De qué trata y qué intentas lograr con esta publicación? ¿Y por qué sentiste que ahora era el momento adecuado para publicarlo? ¿Qué necesidad viste en el campo teatral, pedagógico o en el ámbito social que te impulsó a escribirlo?

Es un libro que intenta acercar las ideas de Brecht a la práctica y desmitificar algunos falsos conceptos. Es muy concreto, breve, pensado para ser útil a quien quiere aproximarse a esta propuesta. Fue escrito en muy poco tiempo. La motivación principal vino de la observación de una necesidad: en el último año y medio o dos, muchas personas que no me conocían, me contactaron, porque encontraban materiales míos en internet en la búsqueda de comprender las ideas de Brecht y mis charlas les resultaban accesibles. Les revelaban un aspecto poco conocido de este método. Entonces se comunicaban conmigo para pedirme materiales o para invitarme a dar clases. En la última invitación que recibí, de una universidad, tomé la decisión de escribir algo porque noté la gran diferencia que podía hacer una intervención pequeña, de dos o tres horas, en la comprensión que los estudiantes tenían sobre el teatro brechtiano. Esa fue la motivación central del libro: generar un recurso práctico que ayudara a acercar el pensamiento de Brecht a quienes querían trabajarlo más allá de la teoría. Como una primera instancia de aproximación.

¿Qué te gustaría que el público o tus estudiantes se lleven de tu trabajo con Brecht y Boal?

Siempre mi mayor interés es que a la gente le sirva lo que hacemos, que le sirva en el sentido de encontrar herramientas prácticas, métodos y estrategias para hacer un teatro que dialogue con su público. A su vez, me resulta importante que, a partir de nuestra experiencia en común, las personas que participan puedan pensar sobre el teatro y la sociedad de una forma más compleja. Creo que lo que más me interesa que le suceda al público y a los estudiantes es que aprendan sobre teatro y sobre la sociedad. Los espacios pedagógicos son también espacios de politización: quienes no tienen ningún tipo de experiencia descubren que el teatro es un espacio público, que entretiene y comunica. En ese sentido, hay una responsabilidad política, que cuando no se hace de forma consciente acaba reproduciendo intereses de la lógica dominante. Lo que veo es que a mucha gente le resulta revelador el curso o las instancias de aprendizaje justamente por comprender que ningún dispositivo de entretenimiento puede ser neutral. Eso es un descubrimiento importante y sorprendente que no sea evidente. Una vez que ocurre como primera instancia, viene lo interesante, todo lo que significa tomar decisiones sobre qué se quiere decir y para quién, y sobre todo que eso sea dicho de una forma que nos permita comprender mejor y no que se imponga como un discurso externo.

¿A qué te dedicas creativamente hoy en día y cuáles son tus planes a futuro?

Como comenté, actualmente estoy dirigiendo un grupo de teatro comunitario, una experiencia que superó mis expectativas y que permite una experimentación muy enriquecedora en la forma teatral, donde también confluyen mis experiencias anteriores con mucha alegría. Por otro lado, estoy realizando un doctorado sobre teatro épico en Argentina, donde tengo el interés de expandir el concepto de teatro épico para que pueda ser usado como categoría de análisis, y también en afirmar que el teatro comunitario es un tipo de teatro épico local. Busco inscribir al teatro comunitario en la historia del teatro épico occidental, que muchas veces académicamente o en ámbitos de formación práctica se entiende como propio de otro universo. El hecho de que no se asocie el teatro de Brecht al amateurismo, impide abrir la imaginación en torno de las formas de representación y sobre todo en torno de su propósito político principal. Poca gente tiene en cuenta la verdadera función y propósito de las Lehrstücke. Creo que es muy útil pensar que la propuesta de Brecht – así como otras modalidades del teatro épico como el Teatro de Agitación y Propaganda, el teatro de Piscator y otras experiencias – estuvo muy ligada al teatro no profesional también. Esto tiene un aporte importante: todo el teatro considerado “al margen” también transforma al teatro insertado en el aparato, y hay una convivencia y enriquecimiento mutuo entre un teatro amateur y otro más profesional. El teatro hecho por no profesionales aborda generalmente asuntos de interés público. Desde mi perspectiva y mi entendimiento, en la búsqueda de Brecht, esto es fundamental que ocurra.

Laura Brauer es profesora de actuación, actriz, directora e investigadora teatral argentina. Se especializa en poéticas políticas, con formación en Teatro del Oprimido con Augusto Boal y en la metodología de Bertolt Brecht en Berlín. Ha trabajado en Europa y América Latina, fue becaria de instituciones culturales alemanas y argentinas, y dirige el grupo de Teatro Comunitario de Saavedra, Buenos Aires.

Epic Theater in Latin America: A Conversation with Laura Brauer

The influence of Bertolt Brecht can be seen in theatres around the world, including Latin America, a region that has not always received the attention it deserves in debates on epic and emancipatory theatre. To explore this landscape further, E-CIBS co-editor Anthony Squiers conducted an email interview with Laura Brauer, a lucid and energetic director, teacher, and researcher whose work is deeply connected to social transformation. In this exchange, Brauer reflects on the current state of epic theatre in Latin America, explores the links between Brechtian theatre and community theatre, and examines the intersection between Brecht’s dialectical approach and the Theatre of the Oppressed developed by Augusto Boal. The result is a situated and vivid perspective on epic theatre today.

Could you briefly tell us about your background and how you found your way to the theater?

My identity was shaped at the intersection of Germany and Argentina, rooted in my grandfather’s exile to the far reaches of the earth and the many years my parents spent in Germany, prevented from returning because of Argentina’s political situation. Although I was born in Argentina, German culture was always present throughout my childhood and teenage years, through my education in a bilingual school and the stays I spent in Germany at age eight and sixteen. From a very young age, I insisted that I wanted to dedicate myself to theater and changing the world. When—years later—in my acting and theater education in Buenos Aires I discovered Brecht’s theater, I was immediately fascinated. His work brought together my two biggest dreams. This was the place from which I wanted to attempt contributing to society. I remembered then that at home we had a German volume of Brecht’s collected works that had belonged to my grandfather, who had even had the chance to see this theater in his time, since he was originally from Berlin. I began reading the plays and the commentaries in German, and I discovered that access in Argentina was extremely limited: there were few materials in Spanish compared to the enormous amount available, and the translations that did exist did not capture the essence of his approach.

That was when I decided to travel to Germany to study epic theater and bring back to Argentina the lesser-known aspects of the Brechtian approach, with a particular focus on acting—which was what most excited me at the time. I wanted to understand how this theater was acted, how this method worked, something I couldn’t find in Argentina despite many attempts.

When I finished my degree in 2005, I began looking for scholarship opportunities to study in Berlin. I was fortunate to access one, which allowed me to complete an internship at the Hochschule für Schauspielkunst Ernst Busch. That initial experience placed me into a virtuous cycle of grants—including from the Berlin Academy of Arts scholarship and the International Theatre Institute (ITI)—that allowed me to spend many months over many years studying in Germany (between 2005 and 2018). During that period, I spent long stretches at the Brecht Archive and the Berliner Ensemble, deepening my research and theatrical practice alongside people directly linked to this tradition. At the same time, during my research period there, I discovered Augusto Boal and the Theater of the Oppressed and parallelly began studying it. For many years, my practice was tied almost exclusively to these two theatrical approaches.

Where are you currently based, and how does that environment influence your theatrical practice?

I am currently based in Buenos Aires, my hometown, after having lived nine years in São Paulo (Brazil) and after previous experiences in Germany. The local theatrical practice influences my work profoundly, above all because here we have what is known as Community Theater, a local phenomenon with more than forty years of history. It was developed in this format by the Catalina Sur group, directed by Adhemar Bianchi, who—along with Ricardo Talento—launched the Community Theater Network and inspired people from different neighborhoods to get involved in this theatrical form.

Community theater is fundamentally a practice tied to place and collective memory. It gathers neighbors—people without formal artistic training—to create a play directed by professionals, with a strong musical component and with the intention of telling the story of their own neighborhood. These troupes, which have multiplied over the decades and now number more than sixty across the country, produce a living, popular theater committed to public issues. They do not seek verisimilitude, illusionism, or the depiction of private stories as traditional drama does; rather, they propose an open, popular, external theatrical language, often performed in public spaces. It is also a large-scale movement: groups range from twenty-five to two hundred participants onstage and use hybrid techniques. They incorporate puppets, dolls, narrative posters, and an enormous creative liberty to represent historical events. The narrative is organized around a concrete political-social objective, always with a strong emphasis on the collective subject over the individual.

I emphasize community theater so strongly because I consider it part of the same historical line in which Brecht’s theater is situated—in other words, a kind of epic theater. I encountered in this theatrical practice something that immediately called to me and something that I consider much more interesting than the stagings of Brecht’s plays or any other expression of the conventional theatrical apparatus in this city.

I am currently conducting research in which I argue that community theater is a local form of epic theater. In this research, I seek to expand the notion of the “epic,” so that it stops being understood as a synonym for “Brechtian” and can instead be used as an analytical category, in contrast to the lyrical and dramatic genres. The specific element of Brecht’s approach would be dialectics; but the epic, as he himself stated, exceeds his own approach.

Since returning to Argentina three years ago, encouraged by Ricardo Talento, I have been directing my own group in the neighborhood where I currently live, called Saavedra. My main theatrical practice is entirely linked to the local experience. We belong to a national network and are part of this local theatrical form. Each group maintains aesthetic autonomy, and my group undoubtedly has much of the type of theater that interests me and with which I trained (not only in Argentina), but it is very open and constantly nourished by the proposals of the working team, other groups, and participants.

You’ve worked extensively with Brecht’s texts and you teach his methods. Could you outline your journey with his work?

I think something very interesting happens to those of us who study Brecht’s ideas intensely and aim to carry them out in practical work: the path becomes very artisan. The beginning—the first times I taught after returning from my first research period and internship in the German theater school—has almost nothing to do with what I do now. At first there was a lot of searching for how to make certain references visible to a local Argentine audience that are completely natural to Germans. German theater, including what isn’t linked to Brecht—has an external, narrative approach that is strongly epic, and the references are very evident to them.

Later, during the years I spent in Brazil, I encountered an approach to theater that was also very different from Argentina’s, and the pedagogical dialogue differed. It was necessary to work with different strategies. For this reason, my path from 2006 to today has changed a great deal, not only because of the incorporation of new knowledge, but also because the classroom was a space of great experimentation, and in that process the ways of tackling the work and understanding what was effective began to shift. Along the way, there was a lot of creativity in devising exercises and a lot of work based on the texts, something that I found essential to learn about in my methodological work during the internship in Germany. We also worked extensively on social themes, always starting from a strong core: What are we doing this for, and for whom? These questions are the organizing principle of the entire scenic approach.

Could you share a significant experience working with any of his texts that shaped how you conceive of epic theater?

A very significant experience in my journey was a staging we carried out in the outskirts of São Paulo. I often work with Brecht’s The Exception and the Rule, and on that occasion, together with a group of students, we staged two different versions of the same text. The objective was to show how—even when working toward the same political purpose and addressing the same audience—it is possible to represent the same material in different ways. Each group chose its own narrative strategies. This made the multiple possible forms of representation evident and worked pedagogically to see how each strategy dialoged with the audience.

The experience was especially enriching because it was the final year of actor training at the Escola Livre de Teatro de Santo André. We presented the play to the Landless Workers’ Movement (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra) (MST), where we later had an especially deep conversation. Later we brought the production to another space, where the audience consisted of workers from a print shop. Many of these young people had never had contact with a play, which made the experience even more interesting. What mattered most was that, from the representation, they recognized aspects of their own work lives in the piece. The discussions that followed were directly related to their working conditions, and that recognition even led some of them to make decisions connected to collective organizing in response to their bosses.

What aspects of Brecht’s works and theories do you find most fruitful for contemporary theater?

I think the most interesting aspect of Brecht’s proposal is his desire to transform everything within theater so that theater itself can fulfill a different social function: contributing to the transformation of society from a perspective in which people can treat each other as friends and see one another as equals. In this sense, his dramaturgy—although fascinating, excellently written, and continues being valid in many respects, also certainly belongs to another time.

The world has changed, and these changes require adaptations and updates so that the texts can speak directly to the problems we face today. For this reason, I consider the most valuable aspects of Brecht’s approach to have two dimensions. On the one hand, his transformative impulse within theater itself, which breaks established conventions and obliges us to create new forms of representation. On the other hand, the idea that plays must be oriented toward provoking a deep dialogue with society, in a way that allows audiences to recognize themselves within the social landscape and understand from which angle they might act to contribute to change and achieve a world that is more just, egalitarian, and mutually supportive.

From your experience, how has Brecht’s legacy been reinterpreted in Latin America?

I believe that the reality in Latin America is very diverse, and the situation changes greatly from country to country. In places like Colombia and Brazil, there were people who went to Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble and brought those references back to their local contexts. This generated a line of work based on this theater but suitable in a specific way, with a depth difficult to compare to countries where this mediation did not occur, such as Argentina or Uruguay.

In these latter countries, Brecht was interpreted mainly through his texts, which meant working with theory without a practical reference point. For that reason, in those countries, one usually encounters a harder, solemn, and less understood Brecht, despite him being fundamentally an author for study and staging.

In São Paulo, by contrast, a kind of “Brechtian capital” seems to have taken shape, given the number of groups that identify as such and their connection to a form of theater deeply linked to social interests. Along the same lines, the work of Augusto Boal and the Theater of the Oppressed can also be included.

Unlike what I was able to observe in Germany, I believe that in Latin America there is still an approach tied to the ideological perspective on Brecht. In Germany, by contrast, I encountered a stance closely associated with the idea that we live in a moment in which the Brechtian perspective on the world would be considered something of the past, and where the contemporary can no longer be thought of in ideological terms as it was when Brecht wrote. That shift means that his legacy there tends to focus mainly on formal aspects: narrative fragmentation, episodic dramaturgy.

Whereas, in Latin America—as far as I understand it—there remains a strong interest in Brecht tied to his critical view of the world, to his invitation to reflect on social conditions, and to his desire for transformation. That is perhaps the most significant difference.

Do you think there is a new generation of creators on the continent who are taking up or transforming the Brechtian legacy, today?

As mentioned earlier, there are theatrical approaches we could call modalities of epic theater, even if they are not strictly Brechtian because they do not preserve dialectics as a central mechanism. Still, they belong to the same historical tradition that Brecht’s theater belonged to: a tradition that seeks to intervene in society and contribute to its transformation.

In Brazil, for example, we encounter a fundamental relation in the Theater of the Oppressed, which can be thought of as a local form of epic theater. In Argentina, in the same way, community theater uses staging devices where the collective and the social are converted into theatrical material and enter this tradition.

However, if I have to think strictly in terms of Brecht’s textual material, the productions of his plays staged in traditional theaters seem hardly connected to the original intent. Many of them seem to be done by people who are not specialists in the field or who are not really familiar with Brechtian theater.

How do Boal’s ideas and Brecht’s ideas dialogue in your practice? Do you find tensions or complementary aspects between the two?

I believe they are two very different approaches. Brecht’s approach processes, as I understand it, a much greater degree of sophistication. Augusto Boal’s approach, being simpler in its structure, is also easier to put into practice, and for that reason it functions—just as he said—as a true toolbox adaptable to any context.

The Brechtian approach, by contrast, does not work this way. It is much harder to condense and requires continuous study. It requires an understanding of how dialectics work, which is not easy. Those of us who study Brecht’s theater know it is a study that never ends.

The Theater of the Oppressed, on the other hand, has the limitations inherent to anything that aims to be accessible and immediately applicable. And it is essential that approaches of this kind exist. Precisely because it aims to be a tool, it loses certain layers of complexity that are present in Brecht.

For this reason, both paths are very different, even though they share a common interest: to contribute to social transformation through the language of theater.

In your work with communities and in nontraditional contexts—such as prisons or schools—how do these influences come together?

In nontraditional contexts, I have worked quite a bit by combining both approaches. I usually begin with Theater of the Oppressed because it has very dynamic, accessible games and exercises intended for people without theatrical experience. After working specifically with image theater, analyzing situations, and discussing what emerges conceptually, I move to a second stage in which I introduce the reading of a Brecht play or poem.

From that material, we work freely on how to stage it. We do not adhere rigidly to the text, but we do respect the contradictions it presents. This method of working has always functioned well: theatrical approaches that are relevant for the participants are arrived at, using a Brechtian text as the trigger.

Your new book, Brecht en la práctica (Brecht in Practice)— “a clear, practical, dialectical exploration of Brechtian theater focused on analyzing, creating, and transforming reality through the stage”—what can you tell us about it? What is it about, and what are you trying to achieve with this publication? And why did you feel now was the right time to publish it? What need did you perceive in the theatrical, pedagogical, or social fields that motivated you to write it?

It is a book that seeks to bring Brecht’s ideas closer to practice and to demystify some false concepts. It is very concrete, brief, and designed to be useful for anyone who wants to get closer to this approach. It was written in a very short period of time. The main motivation came from noticing a need: over the last year and a half or two, many people who did not know me reached out because they found my materials online while searching for ways to understand Brecht’s ideas, and my talks felt accessible to them.

They revealed a little-known aspect of this method. So, people wrote to me asking for materials or inviting me to give classes. In the last invitation I received—from a university—I decided to write something because I noticed the big difference a small session, two or three hours long, could make in how students understood Brechtian theater. That was the central motivation behind the book: to create a practical resource that would help bring Brecht’s thinking closer to those who wanted to work with it beyond theory, as an initial stage of engagement.

What would you like audiences or your students to take away from your work with Brecht and Boal?

My greatest interest is always that what we do is useful to people—useful in the sense of discovering practical tools, methods, and strategies to create theater that genuinely dialogues with its audience. In turn, it is also important to me that, from our shared experience, those who participate can think about theater and society in more complex ways.

I believe what most interests me is that audiences and students learn about theater and about society. Pedagogical spaces are also spaces of politicization: people with no prior experience discover that theater is a public space that entertains and communicates. In that sense, there is a political responsibility, and when this is not done consciously, it ends up reproducing the interests of the dominant logic.

Laura Brauer is an Argentine acting teacher, actress, director, and theatre researcher. She specializes in political theatre practice, with training in Theatre of the Oppressed with Augusto Boal and in the methodology of Bertolt Brecht in Berlin. She has worked in Europe and Latin America, was a fellow of German and Argentine cultural institutions, and directs the Teatro Comunitario de Saavedra group in Buenos Aires.

Cover photo: Colectivo Saavedrépico en Hurlingham. 2025. Photo: courtesy of Joaquin Penna.