It is well known that Brecht’s Epic Theatre was especially catered to the working class. As he states, its “representations of human social life are designed for river-dwellers, fruit farmers, builders of vehicles and upturners of society, whom we invite into our theatres and beg not to forget their cheerful occupations while we hand the world over to their minds and hearts for them to change as they think fit.”[1] This desire to mobilise workers was central to his aesthetic social activism and artistic mission; however, his relation to the working class is a deeply complex question.

Brecht was born into a relatively affluent family in Augsburg. Within the social hierarchy, his upbringing, education, and early success, most notably the financial windfall from The Threepenny Opera, clearly positioned him higher than the working class he championed. Furthermore, as a white, male, heterosexual intellectual with petite-bourgeois roots, Brecht occupied multiple layers of social privilege, which inevitably set him apart from many in the working-class audiences he sought to empower. Nevertheless, Brecht took his allyship with the working class so far that he typically wore “the grey work jacket, the collarless shirt without a tie, and the worker’s trousers—the timeless uniform of the proletarian.”[2]

This wardrobe was a deliberate visual signification of his solidarity with the working class and his rejection of bourgeois subcultural norms. Dressing in this way constituted a symbolic practice, a visible performance through which he signalled his values and political allegiance. His clothes indicated he was a fellow traveller, a comrade, and operated, although counterintuitively, as a form of what Bourdieu referred to as ‘objectified cultural capital.’[3] Objectified cultural capital consists of material objects like clothes, books, or works of art which say something about someone and what they know. Normally, objectified cultural capital is seen as enabling upward mobility because it marks having common ground with higher-status groups. Brecht’s case is interesting because on the surface it seems like he flips that logic. It looks like he used his clothing not to climb into the bourgeoisie, but to reposition himself downward to the working class. Yet Brecht didn’t see this in terms of downward mobility at all. On the contrary, he understood his alignment with the working class in terms of opportunity, development, and the advancement of his own class interests as a member of the intelligentsia.

The intelligentsia is a social class whose economic role is to produce, interpret, and circulate ideas. Writers, artists, academics, and cultural critics fall into this class. In an important and revealing fragment written around 1929, in which Brecht discusses the Expressionist poet Gottfried Benn, he offers a concise theorization of the relationship between the intelligentsia and the working class.[4] His argument proceeds on the premise that the intelligentsia is not a neutral group in society but a distinguishable social stratum that is impacted by and has a unique set of material conditions. Even when intellectuals align politically with the working class, this does not dissolve their specific class character.

To illustrate this point, Brecht invokes the First World War as a historical example of conflict between the interests of the working class and those of the intellectual class. At that time, most intellectuals, he argues, placed their ideas at the service of bourgeois interests because doing so promised recognition and remuneration, that is, because they felt it was in their interests to do so. In doing this, they contributed to sending the working class into war and the machines and weapons they designed maimed and killed them. For Brecht, this history demonstrates that the proletariat has good reason to mistrust intellectuals, since they can readily side with ruling-class interests against them. At the same time, it reveals that the ruling class is dangerous to the intelligentsia as well. A Germany figuratively and literally reduced to rubble proved catastrophic for both groups. Workers and intellectuals alike found themselves living amid the same ruins.

In the fragment, Brecht therefore argues that the intelligentsia ought to align with the working class rather than with the ruling class. Yet he does not frame this alignment in romantic, altruistic, or charitable terms. Social movements, he insists, are driven by interests, not sentiment. Brecht is not alone in thinking this; it is a basic assumption of most of the scholarly literature in the social sciences, which examines social movements.[5] For Brecht, intellectuals cannot effectively join the working class struggle out of moral duty; their alignment must be grounded in their own class interests, rooted in their specific economic and productive function. The question then arises: if the workers’ movement is designed to liberate the proletariat, how did Brecht see the intelligentsia advancing its own interests by aligning with it?

To answer this, Brecht first needed to provide an accounting of what was in the intelligentsia’s interests. He argues that the interests lie in the further development of its intellectual and creative capacities. Although Brecht doesn’t specifically make the connection, his line of argumentation is a familiar one in Marxist thought where personal development and self-actualization are seen as grounded in the concept of human productive activity. For Marx, labour is not merely a means of survival but, drawing on Feuerbach’s idea of species-being (Gattungswesen), it is the defining feature of human beings. Through labour, humans externalize their capacities, transform nature, and in doing so, transform themselves. In this way, work has the potential to be a medium of self-realization: it allows individuals to develop their powers, intelligence, imagination, and social bonds. Marx, however, argues that under capitalism, this potential is undercut. In the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, he argues that wage labour becomes alienated labour: workers are separated from the products they create, from the process of production, from their fellow workers, and ultimately from their own human essence. As a result, instead of fostering development, it stunts and fragments the individual.

While Marx was primarily interested in the topic from the perspective of the working class, Brecht applies this same logic to make sense of the intelligentsia’s structural position in capitalist society, contending that under capitalism, the intellectual is similarly constrained by what he calls the “commodity character of the intellect.”[6] Intellectuals are workers who produce knowledge, art, and culture. Like the proletariat, they do not own the means of production; they sell their intellectual capacities on the market as labour power and then must surrender the fruits of their labour to others who reap profit from them. Like manual labour, then, intellectual labour is subject to exploitation. It generates value that is appropriated by others. Furthermore, as with manual labour, intellectual workers have little to no control over the products they produce. Their work is constrained by the dictates of profitability, and they are subjected to the whims of those who control capital and distribution. Artists and thinkers are dependent on publishers, producers, or patrons who determine whether their work circulates, in what form, and under what conditions. This dependency curtails the full development of intellectual labour by tethering it to market imperatives. In this respect, the structurally subordinate and dependent position of the intelligentsia within capitalism is analogous to that of the proletariat, whose labour is likewise commodified and subject to the same forces.

In Life of Galileo (1943), Brecht revisits this question of the intelligentsia, the commodity character of the intellect, and class alignment more concretely. Early in the play, Galileo goes along with the commodification of his intellect because he needs money to support his household and his scientific work. He develops and sells a telescope to wealthy patrons, illustrating how intellectual labour functions within market relations. However, when his astronomical discoveries later empirically falsify the Church’s geocentric doctrine, his intellect ceases to be profitable and instead threatens the ideological foundations of the ruling class’s power. At that point, it becomes dangerous to the ruling class and the Inquisition pushes back. Here we see that Galileo’s intellectual development is curtailed. His intellect compels him to the stars, but the ruling-class powers-that-be and the threat of torture prohibit the further development of his intellectual and creative activity. By remaining in alignment with the ruling class, he is unable to continue developing himself through his labour.

However, in an exchange between Galileo and a character known as the Little Monk, Brecht shows that although Galileo’s intellectual pursuit in the heavens has no value for the ruling class, that intellect can still be of use to the subaltern classes, and that by aligning with the subaltern classes he can pursue his intellectual labour toward its greater potential and thus develop himself to his greater potential. Although the Little Monk is convinced by Galileo’s discoveries, he urges Galileo to remain silent for the sake of the peasants, whose endurance in a life of toil and hardship, he argues depends on their religious illusions. Galileo rejects this paternalism, arguing that ideology sustains exploitation and that science can instead expose subjugation and materially improve life. He drives the latter point home by saying, “my new water pumps can work more miracles than your preposterous superhuman toil.”[7]

In the play, Brecht lays out two alternatives for the intelligentsia: alignment with the ruling class, which confines intellectual development to the demands of profitability, or alignment with the oppressed, which enables the fuller development of intellectual labour as a transformative social force. This dilemma is not confined to Galileo’s historical moment, nor that of Brecht. For contemporary intellectuals, the decisive issue remains one of allegiance. We may seek validation within existing hierarchies, converting our intellect into a resource that stabilizes the prevailing order, or we may side with those subjected to exploitation and precarity, recognizing that our own autonomy and creative development ultimately depend on broader social transformation.

For Brecht, the emancipation of the intelligentsia is inseparable from that of the proletariat. Only by binding our fate to the working class can intellectuals secure the conditions under which our creativity, independence, and cultural contributions can flourish. His solidarity with workers was therefore not a matter of sympathy or moral duty but a recognition of shared material interests. For Brecht, the intelligentsia and the proletariat may be distinct classes, but their liberation is bound together in the struggle to abolish capitalist society itself.

Anthony Squiers, PhD, Habil. is a faculty member at AMDA College of the Performing Arts and co-editor of E-CIBS. He is the author of An Introduction to the Social and Political Philosophy of Bertolt Brecht and Bertolt Brecht’s Adaptations and Anti-capitalist Aesthetics Today.

[1] Brecht, Bertolt. Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic. Edited and translated by John Willett, Hill and Wang, 1964, p. 185.

[2] Brecht, Bertolt. »Unsere Hoffnung heute ist die Krise«. Interviews 1926–1956. Edited by Noah Willumsen, Suhrkamp Verlag, 2023, p. 301. My translation.

[3] Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice, Harvard University Press, 1984.

[4] Brecht, Bertolt. Brecht on Art and Politics. Edited by Tom Kuhn and Steve Giles, translated by Tom Kuhn, Steve Giles, and Laura Bradley, Bloomsbury, 2003, p. 83.

[5] E.g. Resource Mobilization Theory: John D. McCarthy and Mayer N. Zald, “Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A Partial Theory,” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 82, no. 6, 1977, pp. 1212–1241; Mayer N. Zald and Roberta Ash, “Social Movement Organizations: Growth, Decay and Change,” Social Forces, vol. 44, no. 3, 1966, pp. 327–341. Political Process / Political Opportunity: Doug McAdam, Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930–1970, University of Chicago Press, 1982; Sidney Tarrow, Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics, Cambridge UP, 1994; Doug McAdam, Sidney Tarrow, and Charles Tilly, Dynamics of Contention, Cambridge UP, 2001. Rational Choice / Strategic Approaches: Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups, Harvard UP, 1965; William A. Gamson, The Strategy of Social Protest, Dorsey Press, 1975. Marxist / Class Interest Approaches: Theda Skocpol, States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China, Cambridge UP, 1979; Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward, Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail, Vintage, 1977.

[6] Brecht, Brecht on Art and Politics, p. 83.

[7] Bertolt Brecht, Life of Galileo, trans. Wolfgang Sauerlander and Ralph Manheim, in Brecht: Collected Plays, Vol. 5: Life of Galileo, The Trial of Lucullus, Mother Courage and Her Children, ed. Ralph Manheim and John Willett (New York: Vintage Books, 1972), p. 57.

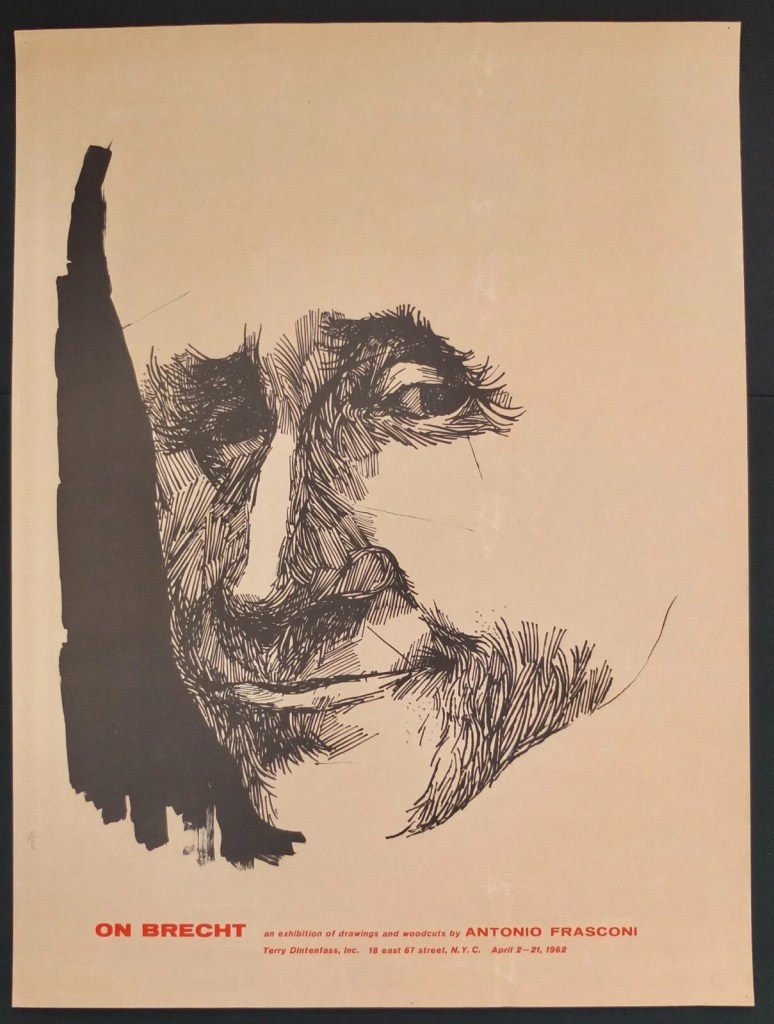

Cover Photo: Bertolt Brecht, c. 1933. Photograph by Grete Stern. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution (NPG.85.94). © Estate of Grete Stern / ARS, NY.