IN THIS ISSUE

Statement from the IBS Steering Committee on the Arrest of Members of the Freedom Theatre Jenin

REFLECTIONS FROM OUTGOING IBS OFFICERS

The International Brecht Society—Reflections on a Turbulent Decade (Stephen Brockmann)

A Short Note of Thanks (Kristopher Imbrigotta)

RESOURCES

Website: Brecht in/au Canada (Joerg Esleben)

ESSAYS AND INTERVIEW

IBS in Israel: Mit dem Rücken zur Wand (Torben Ibs)

BB in Brazil: Then and Now (Marc Silberman)

1. Dialectics of Form in Buying Brass (Sérgio de Carvalho)

2. Brecht and the Measure of Distances: An Interview with José Antonio Pasta Jr. (Sérgio de Carvalho and Maria Eduarda Castro)

PERFORMANCE REPORTS

1. BB on Love and War (Tom Kuhn) and Performance Review (Liam Johnston-McCondach)

2. BB in Kolkata

Breaking the Fourth Wall Festival: Rediscovering Brecht’s Timeless Relevance (Abhilash Pillai)

DOCUMENTATION: BRECHT’S HOFMEISTER ON TOUR

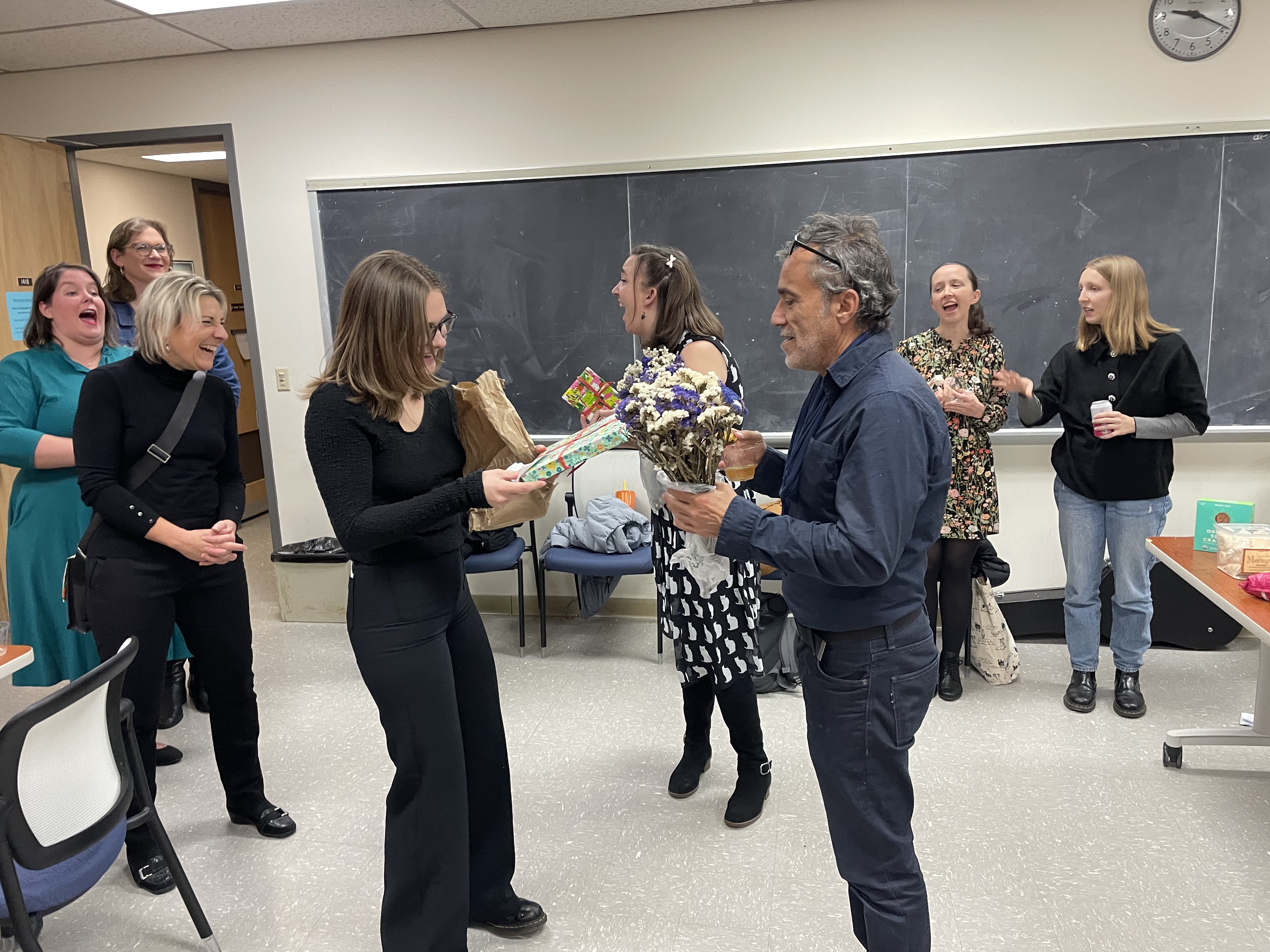

1. Adaptations with Jürgen Kuttner on Tour in the Midwest (Marc Silberman)

2. University of Wisconsin–Madison: Kuttner in Madison (Melissa Sheedy) and Interview with Jürgen Kuttner (Zoe Jaeger, Annika Kline, Collin Queen, and Melissa Sheedy)

3. Indiana University Bloomington: Hands On! Karaoke Theater’s Der Hofmeister (Cynthia Shin)

4. Truman State University: Kuttner in Kirksville (Jack Davis)

Statement from the IBS Steering Committee on the Arrest of Members of the Freedom Theatre Jenin

The Steering Committee of the International Brecht Society was informed about the arrest of the artistic and managing directors of the Freedom Theatre Jenin by Israeli Defense Forces last Thursday, December 14, 2023. Mustafa Sheta and Ahmed Tobasi are well-known artists and have been active in peace work and Palestinian-Israeli understanding for many years. We are glad that Ahmed Tobasi was released the next day, but we strongly recommend the release of Mustafa Sheta as soon as possible, because we are not aware of any connection between him and the terrorist attacks on Israel on October 7, 2023. As much as the IBS continues to support our Israeli colleagues who maintain cultural and social relations with their Palestinian neighbors, we also endorse the efforts of cultural institutions like the Freedom Theatre Jenin to continue the dialogue that is so necessary between both sides – which will be all the more important when the terrorist and military actions are over and a peaceful coexistence of all people in Israel and its neighboring states must become possible.

Stephen Brockmann, President, IBS

Micha Braun, Vice President, IBS

[Back to TABLE OF CONTENTS]

Reflections on a Turbulent Decade

by Stephen Brockmann

Being president of the International Brecht Society for the last ten years has been one of the greatest honors and pleasures of my life. The IBS is a unique organization, unlike any other that I know, partly because Brecht himself is so fascinating and provocative, but also because the people who are attracted to Brecht tend to be dynamic, committed, against-the-grain thinkers who can generally be counted on to bring new perspectives and constructive suggestions to whatever situation they happen to find themselves in.

During my presidency there have been three IBS symposia, each of them, in their own ways, stunning successes. The 2016 Recycling Brecht symposium in Oxford, England was a large, exciting, and intellectually fruitful event that also served as a capstone for the multiyear project of creating a reliable edition of Brecht in English translation (the Methuen-Bloomsbury edition spearheaded by the extraordinary Tom Kuhn). Adding to the drama of the symposium, of course, was the Brexit referendum, which occurred two days before the symposium began. (You really can’t make these things up!) Partly as a result of that, Brecht and political theater seemed even more relevant after June 23, 2016 than they had been before. Who knew at the time that the situation was about to get even worse with Donald Trump’s ascent to the presidency of the United States a few months later? Trump has always seemed to me rather like a figure invented by Brecht himself for a play like Turandot oder der Kongreß der Weißwäscher or, indeed, Der aufhaltsame Aufstieg des Arturo Ui, which suddenly became hugely popular in 2017 and thereafter.

After the excitement of Recycling Brecht I thought that the organizers of the 2019 Leipzig symposium, Brecht unter Fremden/Brecht Among Strangers, would have a difficult time living up to the precedent set in Oxford. This was the first IBS symposium outside of Berlin held in what used to be called the “fünf neue Länder” or the “Beitrittsgebiet,” i.e., in the former German Democratic Republic. Although we didn’t exactly have the political drama of Oxford and Brexit (for which I am very grateful!), the symposium was absolutely packed with exciting panels, keynotes, and performance events, and it featured a close and fruitful cooperation with the Schauspiel Leipzig, which even offered us excellent space to conduct the symposium and also opened their doors and performances for us. As had also been the case in Oxford, many students were among the participants in the symposium.

Then, just last year, in December of 2022, the IBS met for its seventeenth symposium in Israel under the all-too-apposite heading Brecht in Dark Times: Racism, Political Oppression, and Dictatorship. I wish this title had not been as relevant as it turned out to be. As we were meeting in Tel Aviv, Haifa, and Jerusalem in the context of the IBS’s first “wandering” symposium, Israel was in a transition from a relatively moderate to a hard-core, right-wing government. Demonstrations and protests were already beginning to occur, and shortly after symposium participants left Israel, protesters went out onto the streets in the largest mass movement for democracy and the rule of law that the country has ever seen. Of course, all of this was still many months before the brutal and murderous conflict that has engulfed Israel and Palestine in the autumn of 2023, starting with the appalling terrorist attack by Hamas on Saturday, October 7. As I watch all of this in horror from Pittsburgh—the site of the worst antisemitic massacre in U.S. history on October 27, 2018, not far from where I live—I can only hope and plead for restraint, dialog, and compassion.

What makes an IBS symposium so radically different from typical academic conferences and symposia? A number of things, I think. First, IBS symposia are never just academic. They always involve performance, music, art, and participatory elements. Sometimes it seems to me that IBS symposia are “learning plays” on a rather massive scale, traveling from country to country—in the last ten years from the United Kingdom through the Federal Republic and on to Israel. And then, in the near future, we will meet in British Columbia on the far western shore of the North American continent, to confront Brecht and the Anthropocene, co-organized by Elena Pnevmonidou and Kristopher Imbrigotta. Second, because IBS symposia tend to have about 90-130 participants, all of them—by definition—intensely devoted to Brecht and political theater, they foster and encourage an esprit de corps that I have never experienced at any other symposia: a kind of summer camp atmosphere for Brecht and theater enthusiasts. Third, IBS symposia bring together multiple generations, from the most experienced and renowned Brecht scholars who have been publishing their work for many decades to younger generations and even students who might not have heard of Brecht just a few weeks before the symposium began. (I remember after the Leipzig symposium one of these young people enthusiastically writing to me and declaring that he was immediately going to become a member of the IBS.) And fourth, IBS symposia tend to bring together scholars of theater and scholars of literature—as well as music and the arts—from all over the world in ways that generally do not occur in other, more traditional, venues. They are genuinely interdisciplinary and international in scope.

Our symposia are vitally important for our mission and for Brecht scholarship. Year in and year out, however, the Brecht Yearbook establishes continuity and sets the tone for scholarship on Brecht. Of course, there are vital synergies between the Yearbook and the symposia. Markus Wessendorf, our current Yearbook editor, was also the primary organizer and host for the thirteenth IBS symposium in 2010, Brecht in/and Asia at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, and he served as guest editor for Yearbook volume 36, which had the same title. As Yearbook editor in 2006, the year of the fiftieth anniversary of Brecht’s death, I myself served as a co-organizer for the symposium Brecht and Death in Augsburg, the city of Brecht’s birth and then a year later as a co-editor of the Yearbook volume Brecht and Death/Brecht und der Tod. Inevitably there are spillover effects from the symposia to the Yearbook, and vice versa. But even in the time between our symposia—which is most of the time—the Yearbook provides continuity and leadership in Brecht scholarship. It establishes precedents, guidelines, and norms, which are vital for any living field of scholarship and endeavor. The Brecht Yearbook also serves as a key publication outlet for reviews of new Brecht scholarship, and, thanks to vital coordination with Erdmut Wizisla and the Brecht Archive in Berlin, it even occasionally publishes previously unpublished work by Brecht himself. I have been extraordinarily fortunate, during my presidency, to have worked with two talented editors of the Brecht Yearbook: Theodore F. Rippey and Markus Wessendorf. Since I worked as editor of the Yearbook myself from 2002-2007, I know how challenging and exciting it can be, and I want to thank both Ted and Markus for their tireless and productive work.

During my presidency our other journal, Communications from the International Brecht Society, shifted from an annual, bound journal to a biannual electronic journal: e-cibs, electronic communications from the international brecht society. The first editor I worked with was Andy Spencer. Since 2016 I have worked with Jack Davis and Kristopher Imbrigotta. I like the electronic format of e-cibs because it allows quick reactions—for instance, reports on our symposia and conference panels, performance reviews, or even, on a more somber note, obituaries. If you really want to know what is happening inside the IBS as an organization, e-cibs is the place to find out. And so to me e-cibs is another vitally important part of what we do as an organization, and I want to thank Jack and Kris, and also Andy, for their amazing dedication to the journal and to the IBS.

Of course, as Brecht himself knew all too well, “Geld ist eine andere Sache.” The person who deals with this “andere Sache” in the IBS is our treasurer, Sylvia Fischer, and before her, Paula Hanssen. Since I myself am not good at dealing with the “andere Sache,” I am immensely grateful to both Paula and Sylvia for taking on this frequently thankless but vitally important task. The IBS could not function without money, and I have to confess that money has been one of the most difficult challenges of my presidency (precisely because I don’t know much about it). Starting with Yearbook 40 (2016) the IBS went from self-publication to contracting with Camden House as our publisher. The result has been a huge improvement for the layout and visual impact of the Yearbook and also an excellent streamlining of our production processes and timelines. However, I did not sufficiently understand the financial implications of the move from self-publishing to engaging a professional publisher: a drain on the IBS budget, initially, of several thousand additional dollars per year. The simple fact of the matter is that self-publishing (using volunteer labor) is considerably cheaper than engaging a professional publisher—even if the professionalism produces better outcomes. As a result, our reserves began dwindling, and we had to take measures to improve our financial outlook. Those included canceling subsidies for future symposia (which we provided up through the Leipzig symposium) and also raising IBS membership fees and the price of the Yearbook (which is our main annual expense). Thanks to Sylvia Fischer’s able and firm guidance, we are now in a much better financial situation than we were three or four years ago. But we have to continue to be vigilant and careful with our money.

[Back to TABLE OF CONTENTS]

A Short Note of Thanks

by Kristopher Imbrigotta

I would also like to take the opportunity to write a few words as I conclude my tenure as co-editor of e-cibs. My current co-editor, Jack Davis, and I began our positions after an IBS meeting in 2016 and subsequent elections with the hope of transporting Communications into the digital age from a yearly paper publication. The reimagined online version of e-cibs that you are reading now is the culmination of all that planning and work! In the online format, we can deliver additional content – not simply texts or images, but also links to other content, videos, and sound files – which we hope has been an added plus for our readers. It has truly been a wonderful experience publishing work from colleagues around the world. However, I feel that after almost 7 years (and 15 issues) it is time to step back in order to focus on other things, perhaps in a different capacity within the IBS, and allow the next editors to continue to take e-cibs in new directions…and, after all, change is a good thing (as BB puts it):

Ein Mann, der Herrn K. lange nicht gesehen hatte, begrüßte ihn mit den Worten: “Sie haben sich gar nicht verändert.” “Oh!” sagte Herr K. und erbleichte.

It is with deep gratitude to the multitude of colleagues for their collaboration over the years and my own excitement for the future of this publication that I wish IBS members and readers of e-cibs all the best for the coming year!

[Back to TABLE OF CONTENTS]

Brecht in/au Canada: A Research Database and Online Resource

by Joerg Esleben

The website Brecht in/au Canada is the result of a large-scale research project on creative uses of Brecht’s works and ideas in Canada. This project, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, seeks to provide the first comprehensive documentation and analysis of the ways in which Brecht’s oeuvre has been used and recontextualized in the country, primarily in theatre, but also in other fields of cultural production. To this end, a team under the leadership of Joerg Esleben has been combing through newspapers, archives, and online sources, and conducting interviews with theatre artists and scholars, in order to unearth as many Canadian Brecht events as we can find. The scope is very broad, ranging from high school theatre to professional productions at the National Arts Centre of Canada. The bilingual website (in English and French) is conceived as a research tool supporting scholars and students investigating Canadian theatre history or global uses – a term we prefer to “reception” or “appropriation” – of Brecht’s work, a teaching resource for educators at the secondary and post-secondary levels, and a reference tool to help theatre artists interested in contextualizing their work on Brecht. The backbone of the resource consists of a database of hundreds of Canadian manifestations of creative uses of Brecht’s work from the 1940s to the present, providing basic information on the content, dates, locations, and creators and contributors of each event. The vast majority of the catalogued items are productions of translations and adaptations of Brecht’s plays throughout Canada, most in English or French, some created by Indigenous artists, some in German or other languages. Other kinds of creative use, such as song and poetry recitals, radio and television broadcasts, visual art works, and literary treatments, have also been included. The database is searchable by numerous parameters (including geographical locations, decades and years, organizations, individual creators, and original German titles of Brecht works). It will be continually expanded and updated. The website also provides space for more detailed documentation and analysis of aspects of Canadian uses of Brecht, e.g. in the form of interviews and exhibits, some of them student-generated. As an additional service to users, the site includes pages with links to online resources related to Brecht and to Canadian theatre. Finally and importantly, it also invites users to contribute information and materials to enhance the resource.

[Back to TABLE OF CONTENTS]

IBS in Israel: Mit dem Rücken zur Wand

von Torben Ibs

[Erstveröffentlichung in Theater heute (June 2023); erscheint hier in e-cibs mit freundlicher Genehmigung des Autors]

In Israel befürchten kritische Theatermacher und Intellektuelle einem nationalistischen Sturm. Gleichzeitig blockieren israelisch-palästinensische Theatermacher sich selbst beim Werben um ihre Sache. Eindrücke von der Konferenz der International Brecht Society in Israel.

„Gemeinsam arbeiten konnten wir eigentlich nur in London.“ Einat Weizmann spricht bedrohlich ruhig auf der Bühne des Hebrew-Arabic Theater in Jaffa. Sie blickt zu ihrem arabischen Counterpart Issa Amru, der aber nicht selbst hier stehen kann, sondern durch einen Schauspieler verkörpert werden muss. Der palästinensische Menschenrechtler sitzt an diesem Abend vermutlich in seinem Haus in Hebron. Sie ist Regisseurin, Schauspielerin und Autorin, die sich israelisch-palästinensischen Dokumentartheater verschrieben. Hier im alten historischen Stadtkern zwischen ottomanischen Mauern und dem großen Dauerflohmarkt vor den Toren des von Jahr zu Jahr mehr stahlglasglitzernden Tel Aviv gibt es diese kleine Oase jüdisch-muslimischen Zusammenkommens. Wobei der Name des Theaters genau dieses Label zu vermeiden versucht und die Sprachen, nicht die Kulturen, und schon gar nicht die Religionen in den Fokus stellt. Doch natürlich liegt der politische Anspruch auf der Hand, das Ansinnen nach Dialog, die Hoffnung auf gegenseitige Empathie in einem Konflikt, der in den letzten Jahren mehr und mehr verhärtete Fronten hervorgebracht hat.

Die Wahl der neuen Regierung mit dem von Korruptionsskandalen durchgeschüttelten Benjamin Netanjahu und seiner Koalition mit offen rechtsextremen Parteien, die nicht nur Zugriff auf die israelischen Sicherheitskräfte im Westjordanland beanspruchen, sondern zudem auch die demokratischen Institutionen zu ihren Gunsten schleifen wollen – was im Falle des Verfassungsgericht im ersten Schritt zumindest aufgeschoben ist –, verheißen für die Zukunft des Theaters und der dort agierenden Gruppen nicht unbedingt Gutes. Die anhaltenden Massenproteste wiederum zeigen auch die Kraft von Teilen der israelischen Bevölkerung gegen diese schleichende Entdemokratisierung etwas dagegen zu setzen.

Weizman macht schon seit vielen Jahren Theater als Regisseurin und Autorin und versteht sich als Aktivistin für die Rechte der Palästinenser, was die Förderung ihrer Stücke nicht erleichtert. In dem aktuellen Stück „How to make a revolution“ hat sie Issa Amru zusammengearbeitet. Er lebt in Hebron und betreibt dort ein Zentrum für zivile Friedensarbeit und kennt die Schikanen der Besatzung ebenso wie die Kollaboration der palästinenschen Institutionen der Autonomieregierung mit den Besatzern. Vor einigen Jahren stand er dann, wie so viele vor und nach ihm, vor einem israelischen Militärgericht, weil er vorgeblich einen israelischen Soldaten während einer der zahlreichen, als Schikane empfundenen Ausweiskontrollen beleidigt haben soll. Der Fall bekam aufgrund seiner Prominenz als Menschenrechtsaktivist einiges an Aufmerksamkeit und so beschloss Weizman, daraus ein Theaterstück zu machen, die gleichermaßen aus jüdischen wie arabischen Israelis besteht. Dabei geht es ihr nicht um pures Reenactement der kafkaesken Situation des Militärtribunals, die in kurzen, prägnanten Szenen mit grotesker Komik und viel Akten präsentiert werden, sondern die Produktionsumstände selbst werden Thema. Ihre erste Fahrt nach Hebron, die Situation vor Ort, wo der historische Markt wegen Übergriffe zionistischer Siedler weitgehend geschlossen werden musste und die Spannungen im Westjordanland wie in einem Brennglas gebündelt werden. Die Stadt beherbergt einen religiösen Schrein, der als das Grab Abrahams gilt und auf den Juden wie Muslime gleichermaßen Anspruch erheben. So gibt es an dem Schrein eine Synagoge und eine Moschee, so dass man von zwei verschiedenen Seiten an die Grabstätte herantreten kann. Unter den jüdisch motivierten Siedlern gibt es seit einigen Jahrzehnten die Strategie, solche multireligösen Stätten unter alleinige jüdische Kontrolle zu bringen – also in diesem Fall unter israelische und nicht palästinensische. Sichtbar ist dies vor allem in Ost-Jerusalem, aber eben auch in Hebron. Eben dies bringt Weizman auf die Bühne und sucht dabei konsequent die menschliche Dimension hinter dem Politischen, dem Militärischen, dem Religiösen.

Dabei bedient sie sich trickreich im Werkzeugkasten des postdramatischen Theaters. Da ist etwa die Rolle des Militäranklägers, die kurzerhand einem arabischen Ensemblemitglied über geholfen wird und so dem Spiel eine weitere Ebene verleiht. Auch der Spieler, der Amru verkörpert, wird erst durch ein paar laut gesprochene Regieanweisungen seinen Gestus für die Rolle finden. Zudem ist Weizman nicht nur Spielerin, sondern zugleich Erzählerin und Kommentatorin ihrer Erlebnisse, ihrer theatralen Reise mit dem Menschenrechtsaktivisten, der anfangs nur wenig begeistert von der Idee eines solchen Projektes scheint. Zumal er das Westjordanland nicht verlassen darf, so dass die Regisseurin ihn regelmäßig besuchen muss und die gesamte Recherche in Hebron stattfindet. Schließlich gelingt es beiden mit einem Stipendium des Finborough Theatre Theaters in London sechs Wochen in der britischen Hauptstadt zu arbeiten, wo eine erste Stream-Version des jetzt gezeigten Abends entsteht. Hier war es, wenn auch unter Pandemiebedingungen, endlich möglich, wirklich gemeinsam künstlerisch zu arbeiten. Im Staate Israel gibt es die Freiheit für ein solches Projekt nicht. Die neue Regierung, so befürchten viele, wird die ohnehin engen Spielräume weiter einschränken.

Die besuchte Vorstellung war Teil der Konferenz der International Brecht Society (IBS), die unter dem Motto „Brecht in Dark Times“, als wandernde Konferenz im Dezember an den Universitäten von Tel Aviv, Haifa und Jerusalem stattfand. Alle drei verfügen über Theaterabteilungen die nicht nur Institute für Theaterwissenschaft beherbergen, sondern auch als Ausbildungsstätten für den künstlerischen Nachwuchs dienen. Dass es überhaupt „How to make a revolution“ zu sehen gab, war kein Selbstläufer, sondern brauchte viel Überzeugungsarbeit. Viele Gruppen hatten Anfragen der Universitäten abgesagt, weil sie nicht mit israelischen Institutionen kooperieren wollen. Auch eine geplante Exkursion nach Ramallah musste aus diesem Grund abgesagt werden. Die ganze Absurdität von Boykotthaltungen gegen den israelischen Staat wird hier deutlich, denn die internationalen Gäste hatten so keine Möglichkeit, die existierende Vielfalt an Initiativen und Diskursen außerhalb des Vorträge wahrzunehmen. Doch statt Partner zu suchen, verbarrikadiert sich die israelische-palästinensische Zivilbewegung lieber selbst.

„Brecht in Dark Times“ war das Motto der Konferenz und selbstredend gab es ein buntes Putpourri zum aktuellen Stand der Brecht-Forschung mit der Vorstellung neuer Bücher, studentischen Projekten, Vorträgen, aktuellen Rezeptionen bis hin zu einer Drag-Performance im Lichte Brechts. Die israelischen Gastgeber wollten deutlich politisch Flagge zeigen und bezogen das Motto der „Dark Times“ ganz klar auf die aktuelle Situation in ihrem Land. Hier sehen sich die intellektuellen Kräfte, die sich für Aussöhnung und eine Belebung des Friedensprozess zwischen Israel und Palästina einsetzen, mit dem Rücken zur Wand. Gleich zu Beginn eröffnete der Soziologe und Historiker Moshe Zuckermann mit einer Keynote zu den Gefahren der aktuellen Spielarten des Zionismus, die in letzter ideologischer Konsequenz auf eine vollständige Vertreibung aller Nicht-Juden aus Israel hinausliefe. Dass Israel ein Apartheidstaat sei, das war für ihn (und auch viele andere Israelis auf der Konferenz), keine zu diskutierende Frage, sondern Fakt. „In Deutschland würde ich dafür gesteinigt“, richtete er sich besonders an deutschen Konferenzteilnehmer und warf den Deutschen – auch die IBS ist stark von deutschen Akademikern geprägt – generell eine hohe Naivität im Umgang mit dem Staat Israel. Sonst waren die israelischen Beiträge geprägt vom Vorstellen von Positionen, in denen jüdische und arabische Israelis gemeinsam Kultur als Dialogbrücke einsetzen, betonten aber auch, wie die Spielräume immer kleiner würden, da die Kulturpolitik mehr und mehr auf positive Identifikation mit dem Staat Israel denn auf kritische Auseinandersetzung mit Problemen, besonders dem jüdisch-palästinensischen Verhältnis, setzen würde.

Auch der künstlerische Beitrag zur Eröffnung der Konferenz arbeitet offensiv Überlagerungen von palästinensischen und israelischen Erfahrungen. Die Theaterkünstlerin Ruth Kanner präsentierte Szenen aus „Dionysus at the Dizengof Center“. Das Center ist eine der üblichen gesichtslosen Malls, die Einkaufen zum Spektakel machen. Kanner und ihre Gruppe rekonstruieren in zahlreichen, bisweilen choreografischen Bildern die reale Vertreibungsgeschichte dieses Ortes: von den palästinensischen Bauern, über die jüdischen Siedler nach 1948 bis hin zu den kapitalistischen Investoren, die 1972 mit dem Bau des Konsumtempels begannen. Dokumentarisches und Spielerisches verschwimmen und werden eins und schaffen so einen dunkel raunende Gegenraum zu den geradlinigen Fortschrittserzählungen. Gleichzeitig rühren sie an dem unrühmlichen Startpunkt der Massenvertreibungen der Palästinenser 1948 und arbeiten die menschlichen Schicksale, der Opfer von damals wie auch die der Vertreibungen vor dem Bau heraus. Die aktuelle Situation beschreibt sie in Hinblick auf die neue Regierung als schrecklich, sieht aber auch positives: „Der öffentliche Raum wird gerade zu einer Art Bühne, wo widerstreitende Wahrnehmungen von Wirklichkeit aufeindertreffen. Das ist wirklich inspirierend.“ Allerdings, so betont sie, betreffen diese Auseinandersetzungen im Grunde nur innenpolitische Konflikte, die Palästinenserfrage bleibt bei alledem größtenteils ausgeklammert. Allerdings habe sie auch Plakate gesehen, auf denen stand: „Wir schwiegen zu Besetzung [der palästinensischen Gebiete] – also haben wir jetzt eine Diktatur bekommen.“ Kanner widmet sich in ihren Theaterarbeiten aber nicht nur den brodelnden inner-israelischen Konflikten. Mit ähnlicher Empathie erzählt sie in „Cases of Murder“, basierend auf dem Buch „Mordverläufe“ von Manfred Franke, die Geschehnisse der so genannten Reichskristallnacht aus der Sicht eines kleinen Jungen. Auch hier sind es kurze, genau gebaute Schlaglichter, die weniger auf die Handlung als auf die emotionale Betroffenheit des erzählenden Kindes abzielen. Aktuell arbeitet sie an einem neuen Stück „Aside – Residual Scapes in Israel“ über die Routen von Müll in Israel und was die Deponien überdecken.

Auch jenseits der Nische des politischen Theaters gibt es Kindersorgen zu betrachten. Nicht nur die innerjüdischen Konflikte bieten da genug Stoff (siehe Theater heute 01/23), sondern auch die Weltliteratur. Etwa im Hamlet, den das Habima-Theater auf eine seiner kleinen Bühnen gewuchtet hat. Das Nationaltheater hält sich in seinem Programm von den zeitgenössischen Konflikten eher fern und bietet eine Mischung aus Unterhaltung und Klassikerpflege, wobei letztere, wie der Hamlet zeigt, an zeitgenössische Diskurse ästhetisch wie inhaltlich voll anschlussfährig ist. Regisseur Maor Zaguri kommt eigentlich vom Film und will hier „A new Version“ der alten Helsingör-Story erzählen und tatsächlich ist es eine Inszenierung mit Überraschungseffekt. Hamlet, ausladend gespielt von Ben Yosipovich, ist ein dekadenter Königssohn hat in seinem langweiligen Partyleben eigentlich gar nichts auszustehen. Seine Grübeleien sind hier nicht anderes als eine psychische Störung, Stimmen von außen, tanzend dargestellt durch fünf Tänzerinnen eines ansonsten rein männlichen Ensembles. Alles ist queer angehaucht, es gibt bunte Tanznummern und besonders König Gunther (Asaf Peri) ist immer für einen Scherz zu haben, um seinen Stiefsohn ein wenig aufzuheitern und auch Mutter Gertrud mit Alex Krul als formidablem Crossdresser in feiner Spitze ist kein Kind von Traurigkeit. Kein Staat ist hier aus den Fugen und irgendwas, man merkt es bald, geht in diesem sehr bunten Reigen nicht auf.

Hamlets aufkommende Verbohrtheit, seine immer stärkere Abhängigkeit der ihn buchstäblich umtanzenden Stimmen, die dabei auch seine düsteren Textpassagen sprechen, stören die Tagesabläufe. Die Spielfläche ist von drei Seiten von Sitzreihen umschlossen, immer wieder nutzt Zaguri den ganzen Theaterraum, lässt Spieleri durch die Eingangstüren auf- oder abtreten und schafft zudem mit Miri Lazar veritable Tanznummern, die aber bisweilen bewusst als Parodie daher kommen. Popkulturelle Zitate werden kombiniert mit Mut zum bunten Bild und lassen Hamlet umso stärker dagegen als schwarzen Berg erscheinen. Bis zum bitteren Ende kommt es aber nicht, denn auf dem Friedhof ist Schluß und die Zeit wird rückwärts gedreht (und entsprechend gespielt), denn die Zeit ist aus den Fugen und Claudius war hier gar nicht der Königsmörder. Alle Widersprüchlichkeiten ergeben nun Sinn und unterlaufen doch das Drama vollends. Maor Zaguri ist hier eine rasante und sehenswerte Hamlet-Adaption gelungen, ohne Tragik, aber mit Effekt.

Das Zurückdrehen der Zeit ist im echten Leben allerdings unmöglich, auch wenn sicher viele Aktivisten, dies gerne hätten. Die Zukunft wird zeigen, ob Israel vor einer Tragödie der Demokratie steht oder das ganze als Farce endet. Dramatisch ist es auf jeden Fall.

[Back to TABLE OF CONTENTS]

Brecht in Brazil

by Marc Silberman

The following two articles focus on Brecht in Brazil. Maria Eduarda Castro and Sérgio de Carvalho edited a special section on the topic in the theater journal Moringa: Artes do Espetáculo (Vol. 14, no. 1 / 2023), published at the Universidade Federal da Paraiba in Brazil.

Included among the articles was an interview with Marc Silberman (“Brecht, o Experimentador”), translated by the two editors into Portuguese. This led to the suggestion that we should translate two of the articles into English, to offer Anglophone readers insight into past and current controversies about Brecht’s relevance in Brazil’s theater life. Silberman, who does not speak Portuguese, produced an initial translation using a machine translation tool, modifying many of the mistaken or misleading “choices” suggested by the software based on his knowledge of Brecht and English syntax. Then Maria Eduarda Castro worked with José Antonio Pasta, Jr. and Sérgio de Carvalho in identifying references and challenging words, phrases, and concepts, yielding no fewer than four versions / revisions of the texts. It should be noted that these two English versions are not identical to the Portuguese texts in Moringa. The authors have modified and extended some comments and deleted others that would have needed extended clarification for those unfamiliar with the Brazilian dictatorship in the 1960s/1970s and its aftermath. In the best Brechtian sense, this has been a truly collaborative project.

Sérgio de Carvalho is a playwright and theater director for the Companhia do Latão group in São Paulo, Brazil, and a professor at the University of São Paulo.

Maria Eduarda Castro holds a Ph.D. in philosophy from Pontifícia Universidade Católica in Rio de Janeiro, and is currently a postdoctoral researcher in the School of Communication and Arts at the University of São Paulo.

José Antonio Pasta, Jr. is a senior professor of Brazilian Literature in the Faculty of Philosophy, Letters, and Human Sciences at the University of São Paulo.

Marc Silberman is emeritus professor of German at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

**********************************

Dialectics of Form in Buying Brass

by Sérgio de Carvalho

Brecht gathered and adapted his reflections on theatrical theory in a project called Buying Brass (in German Der Messingkauf). The dialogical form was inspired by Galileo’s scientific writings, which in turn referred to the classical tradition of philosophical dialogues. Brecht worked on the project for more or less 16 years in various phases between 1939 and 1955: a first, intense one between 1939 and 1941, then less regularly between 1942 and 1943, and he returned to the plan in 1945, 1948, and 1955. In the same period, he wrote the Short Organon for the Theatre, imitating the style of Francis Bacon and comprising a topical summary of his thoughts about the theatre organized into paragraphs, which present various internal contradictions. While the Short Organon seeks a synthetic form, Buying Brass expands at all levels the method of contradictions in a more radical way. It is an unfinished work, one of programmatic incompleteness. As a result, it is difficult to say in what ways these discursive and scenic materials could project some “contradictory unity.” Beyond a theorizing poetics about the dialectics of theatre, Brecht imagined a theory in dialectical form, in a scenic sense.

After the author’s death, his collaborator Werner Hecht published an abbreviated edition in which he consolidated various parts in order to yield a sort of narrative logic associated with the “four nights” during which the dialogues would take place. This version makes it easier to follow the relative evolution of the discussions, according to Brecht’s plan to be distributed over the four evenings. In the complete editions, however, Buying Brass is an open-ended, loosely bundled corpus of writings: dialogues, notes, poems, exercises for actors, sketches for future scenes.

The presumed fictional situation is that of a theatre company following a performance of a Shakespeare play, possibly King Lear. Brecht wrote several comments about Hamlet as well, a reference that was retained in the Berliner Ensemble’s staging of a text-version in 1963. After the curtain comes down and the set is being dismantled, the philosopher enters the stage, introduced by the house dramaturg. A circle of chairs is set up. Soon, part of the cast of actors joins them for a conversation about art and other issues. They are accompanied from a distance by the stagehands, who continue with their manual activities and occasionally take part in the debate, which is resumed on the following three evenings. I reproduce one of the descriptions of the characters:

The Philosopher wants to use the theatre ruthlessly for his own ends. It must provide accurate depictions of incidents between people, and facilitate a response from the spectator.

The Actor wants to express himself. He wants to be admired. Plot and characters serve his purpose.

The Actress wants a theatre with an educational social function. She is politically engaged.

The Dramaturg puts himself at the Philosopher’s disposal, and promises to apply his knowledge and abilities to the conversion of the theatre into the thaëter envisaged by the Philosopher. He hopes for a new lease of life for the theatre.

The Lighting Technician represents the new audience. He is a worker and dissatisfied with the world. (Brecht 1965, p. 10)

The formal scheme planned by Brecht engages the difference in perspective between the philosopher and the group of artists, distanced by the work of the “lighting technician” and other stagehands. The contradictory relationship develops not only in conversations and discussions, but also in exercises that can be practiced, insofar as everyone is on stage. Brecht thus was thinking of a theory that becomes practice, to be experimented with, accompanied by observations, models, and workable suggestions that only the poetic activity of staging can facilitate.

In a Journal entry of 12 February 1939 Brecht summarizes the project’s initial intentions:

A lot of theory in dialogue form The MEssingkauf Dialogues (spurred to use this form by Galileo’s Dialogues). Four nights. The philosopher insists on the P-type (planetarium-type, instead of the C-type, carousel-type) theatre purely for didactic purposes, movements of people (also shifts of the emotions) organized as simple models for study purposes, to show how social relations function, in order that society can intervene. His wishes turn into theatre, since they can be implemented in the theatre. From the critique of theatre a new theatre emerges. The whole thing so conceived that it can be performed, with experiments and exercises. Centering on the V-effect. (Brecht 1996, pp. 20-21, trans. modified by Silberman)

The “dramaturgical” plan, in other words, presupposed the initial tension between the philosopher’s artistic vision and that of the artists based on opposing conceptions of the function of art. And the conflict erupts already on the First Night.

Among the many notes for that night’s dialogues two themes stand out. One relates to the philosopher’s own visit and is linked to his instrumental interest in art, understood as a means of scientific knowledge. There is a whole scene about this in the sketches made between 1942 and 1943, which reads at the beginning as follows:

Dramaturg: . . . why not begin by asking our friend the philosopher what interests him about theatre in the first place?

Philosopher: What interests me about your theatre is the fact that you apply your art and your whole apparatus to imitating incidents that occur between people, making your spectators feel as though they’re watching real life. Because I’m interested in the way people live together, I’m interested in your imitations of it too. (Brecht 2014, p. 13)

The artists’ discomfort with the purpose of “imitation” – oriented towards a critical understanding of social life – escalates from there. Despite the intermediate positions, at a certain point the actor ends up explaining the difference in visions. He considers this scientific interest applied to the theatre to be cold, rationalist, and anti-aesthetic. It seems to him, without the phrase being uttered, to be the expression of a vulgar sociology. As the tension rises, a dialectical interaction between the issue and the form of the debate appears on stage when the philosopher, who at first embodies the distanced point of view, seems to get emotional. Confronted with the unease that has arisen, he argues that he is not opposed to “emotions,” to the play of artistic affections. He informs us, however, that his personal pleasure at getting to know society perhaps puts him in a strange place in relation to art:

Philosopher: Oh, I’ve got nothing against emotions. . . I’d like to stress once more that I feel like an intruder. . . The special nature of this interest cannot be emphasized enough, and it strikes me so powerfully that I can only compare myself to a man who, let’s say, deals in scrap metal, and goes to see a brass band wanting to buy not a trumpet or any other instrument, but simply brass. The trumpeter’s trumpet is made of brass, but he is hardly going to want to sell it as brass, according to its value as brass, as so-and-so many pounds of brass. But that is exactly how I am approaching you in my search for incidents between people. . .

Dramaturg: So, your purposes are scientific ones! That’s got nothing to do with art, you know. (Brecht 2014, p. 17-18)

The philosopher’s materialist declaration, which defines the entire corpus of writings and was made in the heat of the debate, is in turn part of the interest in an experimental, scientific, and educational attitude developed by socialist-inspired theatre at the end of the nineteenth century.

As a consequence, a debate on Naturalism appears in several of Brecht’s notes and was possibly scheduled to take place on the First Night. The philosopher’s insistence on paying attention to incidents between people emphasizes his commitment to an objective understanding of social relations. Through theatre he is interested in analyzing “the way people treat each other,” how they deceive each other, how they exploit each other, how they judge each other, but also how they “observe the movement of the planets.” The scientific interest is guided by an ethics of shared knowledge: “Because I wonder about how I myself should behave if I want to succeed and be as happy as possible, and of course this depends on how other people behave, which makes me very interested in that too – and especially in the possibility of influencing them” (Brecht 2014, p. 19).

The production of images must be socially interested. Brecht’s reflections on the legacy of Naturalism were perhaps intended to expose some of the contradictions of this artistic project, which was still relevant for left-wing art. Several texts comment on Stanislavsky’s work. At the same time as the research attitude of that literary movement looked to the future, Brecht sought to demarcate the limits of a fictional imaginary fixed on the depiction of milieu. The dramaturg, who leads the debate on Naturalism, seems to echo a Lukácsian position when he laments how Naturalist plays strip away action and poetry in comparison with the epic scenes from the past:

Dramaturg: The subject matter of the various plays was quickly exhausted. . . And the theatre had sacrificed so much. All of its poetry, and much of its ease. Its characters were as flat as its action was banal. . . they did not depict a single great character or a single plot worthy of comparison with those of the old plays. (Brecht 2014, p. 30)

The presence of this theme in Buying Brass is due to its importance for twentieth-century socialist theatre within the broader aesthetic-literary debate about realism that was rekindled by Lukács’s disciples in the polemics around the status of Expressionism. Brecht, who did not align himself with the generic criticism of the merely descriptive character of Naturalist literature and even less with the unfair attribution of the label “formalist” to any anti-Naturalist, avant-garde experiment, understood that an effective, dialectical Marxist aesthetic would need to be measured by its concrete usefulness, beyond stylistic reductions of a scholastic type, which create – indeed these very – formalist labels against experimental art practices. The great bourgeois novel was complex from the standpoint of the interaction between the individual and the totality because its social material was from a different era. For Brecht, the dehumanization of form in Naturalism originated from a dialogue with social forces that were being observed for the first time. Any political theatre can learn from the limits of that scenic experimentation if it doesn’t disregard the motivational impetus of its didactic attitude.

On the other hand, presenting an external image of reality on stage when the critical perspective is not part of the form is insufficient and can reinforce hegemonic points of view. Not to take sides in art is to take the dominant side, Brecht writes in the Short Organon. The philosopher’s position in Buying Brass is similar: an image of the world should be a workable image, mobilizing, and therefore, to some extent, negative. It should offer itself as a model for studying society, a laboratory for imaginary experiments. This is what the philosopher means when he states: “People can’t demonstrate the law of gravity by dropping a stone, nor by merely giving an exact description of its fall” (Brecht 2014, p. 29-30). It’s not the fall of an individual character that matters, but their contradictory relationship to collective patterns. Similarly, a ball in a game cannot assume the existence of laws of movement, just as a character in the midst of social processes can hardly understand the causality of certain movements in the world of commodity exchange.

The philosopher’s use of metaphors from the natural sciences in this debate is not without contradiction. He seems to insist on the P-type theatre (Planetarium type, rather than the C-type or Carousel type). Some editions leave out the notes on the difference between these models, perhaps imagining that they need no explanation in the discussions of the four evenings because the characters’ visions presuppose them. They allude, however, to Goethe’s and Schiller’s observations on the difference between the dramatic and the epic, already incorporated into Brecht’s early theoretical schemes. In Carousel-type dramaturgy spectators revolve around a fixed axis, with the sensation that they are riding a horse. The horse imitates jumps, makes an emotional circuit, but its dramatic turn takes place in relation to an immobile center. In P-type dramaturgy the spectators are, in contrast, stationary, looking up at the moving stars. By observing the stars’ trajectories, they are encouraged to glimpse the patterns of movement.

For Brecht, however, this dualistic opposition between contemplative and active, so dear to classical, bourgeois thought, is always relative, as the P and C types themselves suggest. And although epic theatre is apparently closer to P-type dramaturgy, this configuration can come close to the “carousel” form when practiced with themes that require displacement. Brecht’s plays, for example, are not just “planetary.” Although they try to discuss causalities of behavior, the characters’ movements are never strictly typical, even much less abstract.

When the philosopher radicalizes his point of view on art’s sociological usefulness, the opposite aestheticism speaks up and claims its place, thus announcing a dimension of autonomy that is necessary for art to be realized. A discontinuous movement of dialectical interactions is therefore projected in the interplay of the fragments. The method of contradictions is not just a theme to be debated but structures, organizes, and sometimes disorganizes Buying Brass’s form. As is the case in the author’s plays, its theorizing sense goes beyond the level of consciousness of those involved, thereby adding irony to the very attempt of philosophical debate, which will have to be interrupted at the end for a bathroom break!

Materials for the Stage and Scenic Materiality

It is an impractical task to try to reconstruct the details of such a complex and incomplete work. Brecht suggested various arrangements for sequencing his themes each night. It is possible, however, to speculate and imagine some avenues for the dialogues. The fundamental idea of Buying Brass is that theatrical theory comprises shifts between the theatrical work, the stage, and the world. It is only in the transitions that the dialectic of an anti-ideological theatre becomes concrete, and this can be observed only in the suspensions produced at different times, with some of these “gestures” – images that concretize social interactions – corresponding to the critical encounter of different dramatic actions. And they may even be ideological in themselves.

Similarly, the estrangement effect (Verfremdungseffekt) cannot be considered only in its technical-formal dimension because historicization can occur in many ways in order to confront the hegemony of dramatic expectation. The recurring demand in Buying Brass to overcome the performance of individualizing identification points to the need to overcome the abstract emotions of dramatic empathy (originating from the concentration of the dramatic structure around the difficulties of the self-reflective protagonists). The “dismantling” of the drama’s ideological core does not imply the absence of divergent dramatic lines arranged in a contradictory relationship.

These transitions, however, depend on a complex dramaturgical construction on the stage, even if it is based on dual schemes. Therefore, it is likely that on the Second Night of Buying Brass the group will begin to discuss the need to “dialecticize” the opposition between individual and class, at the same time as the characters’ dramatic movements become permeable to opposing views. At the level of the dialogic form of Buying Brass the critique of drama gradually becomes “anti-Aristotelian” through the disjunction between the characters (initially shown as typical) and their “thinking.” On the other hand, there seems to be a connection between the poetic search for scenic materiality and the critique of rational or explanatory representation.

Thus, that “the opposition between sobriety and intoxication are both present in artistic enjoyment” is a theme that appears in the fragments (Brecht 2014, p. 44). The metaphor takes shape in the wine glasses that appear in the hands of the team. The wine participates in the process of Buying Brass, and the philosopher will interpret the offer of the drink. It is a symbol of possible interaction, of necessary metamorphoses. On the Second Night the satire about a certain cult of the irrational and the mystery of art, a human activity so often celebrated in terms of an archaic fetishism, perhaps also appears by way of contradiction. The consumption of spectacles is compared to that of intoxicated evenings, because theatre can also be used as a drug for everyday pain and the imagination, and put at the service of the capitalist entertainment market. This observation clashes with the philosopher’s melancholy realization that “at night I’m a mess, just like the city I live in” (Brecht 2014, p. 44).

Surprisingly, the philosopher then promotes a critique of the limits of a certain vulgar application of Marxism. He argues that the classical heritage of dialectical thinking, conceived as a Great Method, is linked to the search for understanding and collective practice. Therefore, it is necessary to be wary of easy generalizations when it comes to interactions between concrete individuals:

Philosopher: I must point out one limitation. . . The laws [Marxist theory] postulated apply to the movement of large units of people, and although it has much to say about the position of the individual within these large units, even this is usually only in reference to the individual’s relationship to these masses. But in our demonstrations we’d be more concerned with the way individuals behave towards one another. (Brecht 2014, p. 40)

In other words, to confirm that life intersects with class struggle and the abstract dynamics of commodification does not mean that a general perspective should be applied to the examination of inter-individual relationships, even though in a theatre interested in this critical type of “demonstrations,” subjectivity should be examined in its relationship with social and economic processes.

The diffuse feeling that “[i]t’s all interconnected in some way, we can feel it, but we don’t know how” (Brecht 2014, p. 36) cannot be challenged by generic refusals to “the system” nor by reductive, fictional mechanisms without risking that the stage becomes a framework of explanatory and comforting abstractions. Hence the philosopher’s foolproof advice to the actors, which already indicates a shift in his thinking, a contradictory view on the applicability of Marxism in the theatre:

Philosopher: If, for instance, you think that a peasant will act in a particular way in a given set of circumstances, then use a specific peasant who has not simply been selected or fabricated for his propensity to act in precisely that way. . . The concept of ‘class’, for example, is a concept which embraces a great many individuals and thereby deprives them of their individuality. There are certain laws that apply to class. They apply to individuals only in so far as those individuals coincide with their class, i.e. not absolutely. . . You are not portraying principles but human beings. (Brecht 2014, p. 76)

The call for a dialectic of the living brings the philosopher’s positions closer to those of the artists. The debates suggest the importance of a crucial connection between intelligibility and the poetic confrontation with the less comprehensible side of life. There are things that cannot be understood, but theatre does not need to praise confusion or difficulty, nor should it fall into metaphysical magic or enlightened self-complacency.

As Mário de Andrade would say, “confusionism” must be rejected, but on the other hand, it’s not possible to represent things clearly that aren’t clear.[1] And there are relationships that, even if they are “not in our control” cannot be excluded from a work of art that aims at the truth. As modern physics claims, scientists influence the imprecise movement of electrons by the very fact of observing them through their microscopes. Brecht, in his Journals, quotes passages by Max Planck on the same subject: statistics fail “when it is a question of the behaviour of isolated electrons” (Brecht 1996, p. 213). Hence the search for a dramaturgy in which atypical behaviors emerge from the movement of typical behaviors with which they interact.

Representation, like the microscope, is not outside the problems it treats because it influences the materials observed. And the appeal of art is not fully conscious insofar as not everything can be understood. The philosopher concludes: “We have to present the clearly defined, controllable elements in relation to those that are unclear and beyond our control, so that these too have a place in our thaëter” (Brecht 2014, p. 54).

Brecht’s thaëter reverses the conventional dramatic scene because it aims to demolish dominant idealisms. At different ideological moments, however, the focus of this dialectical method can vary. Shakespeare’s work appears in Buying Brass because it represents a material, self-critical, historical, and poetic model of classicism, born out of collective effort. Yet his plays already outline a technical operation that was later amplified in the world of drama: producing empathy through the relative structural concentration on the subjective struggle grounded in the protagonist’s moral choices. In Shakespeare, however, individuation is complicated. It has not yet been converted into a generic positivity. The entire structure is not reduced to the protagonist’s movement. Individuation appears distanced by other collective demands and is set against the play as a whole. Shakespeare wrote his plays at a time when emerging capitalism formulates an ideal of the subject’s freedom in the field of political philosophy. His work, however, still contains values inherited from the feudal past.

What Brecht advocates by including one of Shakespeare’s plays as a reference for the project of Buying Brass is the importance of not reading the classic work under the sign of a generalization about the human condition. The representation of Lear’s pain will be falsified if it is unable to show it as the pain of a social group that has lost power and if it is unable to project other collective pains and possible joy. A tragedy of the feudal world’s end, King Lear’s material and gestural aspects need to be brought to life by experimentation in order to dismantle the tendency to reduce emotions to bourgeois individualism.

Brecht devised various exercises for actors. These are practice pieces designed for rehearsals, instruments for “dialecticizing” Shakespearean classics. More important than criticizing a residual ideology is to suggest topical forms of practice. This dimension of “realization” is structural to the project, imagined as an experiment in dialectical performance based on material that calls for intervention. As an example of this task, the Shakespearean intercalary scenes function as a device to prevent the reading of the classic as a stable subjective formation. They are instruments that show what could have happened to the characters before the events shown in Shakespeare’s play, possible dialogues that reveal a world of specific social formations. The same actor who will produce Lear’s wailing lament must therefore ask himself about the relationship between this tragic cry and the suppressed history of the beating of his daughter’s servants, explored in the exercise. Brecht appreciated the impurity and unpredictability of Shakespeare’s theatre. Written in an anti-idealistic way that sought to bring poetry and realism closer together and that fashioned words from action, his plays have a direct link with the production method of Elizabethan theatre. Whoever he was, Shakespeare was the lead playwright in a team of collaborators, writing at the foot of the stage, incorporating the voice of the streets.

The theoretical fragments and debates on “The Street Scene” as a model for epic theatre (Brecht 2015, pp. 176-183), another important theme in Buying Brass, also resemble the collectivized classicity demonstrated by Shakespeare. The Brechtian poetic hypothesis is that the ordinary report about a street accident contains the fundamental principles of epic theatre. No one narrates a lived experience without having a point to put across. It is the critical and interested intent that affects the formulation. Objectification comes from the urgency to expose contradictions and substantiate judgment. That’s why the narrator-imitator doesn’t spend too much time to understand the rivals’ motivations and reasons and “never loses himself in his imitation” because he has a point to make, as evoked in the beautiful poem “On everyday theatre” (translated by Edith Anderson, Brecht 1976, pp. 176-179). “The Street Scene” can inspire a politicized artist if it can dialogue with the world of work and engages a material attitude, as Shakespeare’s theatre did. The synthesis between imaginative stylization and concretizing action neutralizes the formal expectation of conventional drama, based on emotional and confirming abstractions, and it offers a frame for an imagined and vital collaboration with the spectator.

Workers’ Theatre

It is possible to imagine that Brecht planned to describe in the Third Night examples of effective works of theatrical dialectics. In order to stimulate experimental practice, he seems to feel the need to describe model artistic attitudes. Buying Brass is one of the rare texts in which Brecht names his elective affinities, the dramaturgical influences of his youth, the people he admired. He refers to himself as the Augsburger (the city where Brecht himself grew up), the poet who learned theatre by admiring the work of artists such as Büchner, Wedekind, and the clown Karl Valentin, a comedian, musician, and playwright with whom he collaborated. Among the artists mentioned (especially in the dramaturg’s commentaries) is the German director Erwin Piscator. Brecht describes some of his remarkable shows from the 1920s and considers him the “only epic playwright of his time” (apart, of course, from the Augsburger). Dialectical dramaturgy depended on a new type of artistic collaboration, linked to a revolutionary attitude. The theorizing vision makes sense as an egalitarian practice: born of an awareness of limits, it is reformulated by common experience. Buying Brass only discusses dramaturgy, acting, or staging when linking them to how the artistic work functions as a whole. Hence the importance of historical references to people who fought for practical transformations.

Some of the most beautiful passages among the texts are about Chaplin, Piscator, and in particular his companion in art and life, the actress Helene Weigel. In a marvelous text entitled “Weigel’s Descent into Fame,” Brecht describes her inverted “ascent”: celebrated as a great actress in the context of bourgeois culture of the 1920s, Weigel found a new way of acting by taking part in the class struggle. She approached the workers’ world at the same time as she distanced herself from bourgeois cultural standards by which her talent had been acknowledged. She found her style by losing interest in the performer’s personality:

Having expended so much effort in learning how to direct the spectators’ interest towards major themes, namely the struggles of the oppressed against their oppressors, it was not without difficulty that she learned to accept the transferral of this interest from herself – the performer – to what was being performed – the subject matter. Yet it was this that represented her greatest achievement. (Brecht 2014, p. 73)

That’s how the praises of art connoisseurs abandoned her, and she became pursued as a militant. The politicization of her art turned her into a case for the Nazi police:

She continued to perfect her art, and she took ever more significant art to ever deeper depths. And so, once she had completely surrendered and lost her former fame, her second period of fame began: a lowly one, existing in the minds of a few persecuted people, at a time when many people were being persecuted. She was quite content, because it was her goal to be famous among the less fortunate – among as many of them as possible, but even among just these few, if nothing else was possible. (Brecht 2014, p. 74)

Brecht’s poems about theatre, many dedicated to their scene partners, say a lot about his dialectical vision. In general, it is in these poems that his most beautiful formulations on the art of acting emerge. In a writing about an actress (Ruth Berlau) who was working on a character in Nordahl Grieg’s play Nederlaget (1938, Copenhagen, the inspiration for Brecht’s later play Days of the Commune), the actress says: “. . . I / Shall walk on stage as a beautiful woman now wasted / With yellow skin, once soft, now ruined / Desired once, now loathsome / So that everyone asks: who / Did this?” (Brecht 2019, p. 647). The image of lost beauty sums up the duration of time. And the actress speaks the woman’s lines as if they were an accusation. The great artist imprinted on the image the possibility of an unsuccessful revolution and the promise of free action.

The Sixth Sense for History

There are numerous materials from the Fourth Night in which Brecht may have wanted to establish contradictory unities from the materials of Buying Brass. At some point, however, the movement of his theoretical materials reached a limit that demanded a leap to practical implementation beyond the text. Even though it is unrealistic to predict whether the formal movement would turn towards partial syntheses before that point, there is no doubt that he planned at least one central “dialectical twist,” as we read in a Journal note from 25 February 1941: “[T]his is the dialectical twist in the fourth night of the MESSINGKAUF. Here the philosopher’s plan to use art for didactic purposes merges with the artists’ plan to invest their knowledge, experience and social curiosity in art” (Brecht 1996, p. 135).

The combination of skill and liveliness, collective and individual gestures, clarity and confusion, classicity and work, culminates in a reflection on a new concept of beauty. A dialectical theatre cannot give up the right to beauty or lightness, even when confronted with horror. For this to happen, its concept of beauty will have to be of a productive order, inspired by Marxist “classicity” (Pasta 2010). “What makes artificial things beautiful is the fact that they have been skilfully made. . . Beauty in nature is a quality that gives the human senses the opportunity to be skilful” (Brecht 2014, p. 83). The bourgeois opposition between enjoyment and action is “dialecticized” once again: “The eye produces itself” (Brecht 2014, p. 83). The productivity of the senses turns to the superfluous and depends on free time. Beauty resolves difficulties. Thus, collectivized and socialized, beauty offers itself as a political symbol of social justice. The fragments’ movements construct the critical-poetic perspective. Dialectical theory takes place in transit, just as a dialectical theatre must act out contradictions on several levels simultaneously.

Thaëter aims for an emancipatory attitude that feeds on the lived experience of the streets, knowledge of the past, and revolutionary action. It will be experimental as it fights against the forces of death, as it confronts a fascism that is always resurrected when protecting the rate of profit can no longer depend on the mask of democracy. Brecht writes that “it is high time people began to derive dialectics from reality, instead of deriving it from the history of ideas. . .,” because it is not a formal method (Brecht 1996, p. 47). From the perspective of how the materials in Buying Brass evolve, dialectics is the possibility of distinguishing processes in things, in flux, and of making social and artistic use of these processes. Theory emerges as an elaboration of failure, as preparation for future action. And it is realized as practice, hence the founding and organizing aspect of the formal project of this work: all the material is conceived “so that it can be performed” with experiments and exercises.

It is almost certain that these dialogues with tradition and the future, mapped out in the worst years of exile during the Second World War, could only exist in the unresolved form in which we encounter them today. Buying Brass breathes the enjoyment that comes from absence, because “to observe you have to compare, but to compare you have to have already observed.” It is a proposal for action inside and outside of time, a stimulus for visions to become plans, a utopian counterpoint to the brutal and paralyzing dynamics imposed by new cycles of capital.

An example of this activating beauty can be seen in the following fragment, which reflects Brecht’s artistic stance as an artist in those years, when he realized that for existing capitalism nothing more needed to be unmasked because there were no more veils to be removed:

Philosopher: The classic attitude I saw was that of an old worker from a textile factory, who saw a very ancient knife lying on my desk, a rustic table-knife I used to cut pages with. He picked up this lovely object in his great wrinkled hands, half shut his eyes to look at its small silver-chased hardwood handle and narrow blade, and said: “Fancy them making a thing like that in the days when they still believed in witches. . . They make better steel now, but look how beautifully it balances. Nowadays they make knives just like hammers; nobody’d think of weighing the handle against the blade. Of course, someone probably spent several days tinkering about with that. It’d take half a second nowadays, but the job’s not so good.”

Actor: He saw everything that was beautiful about it?

Philosopher: Everything. He had that kind of sixth sense for history. (Brecht 1965, p. 58)

[1] Mário de Andrade (1893–1945) was a central figure of Brazilian modernism. Poet, novelist, short story writer, critic, musicologist, he strongly influenced the transformations of Brazilian art in the twentieth century. Author of an immense number of works, his novel Macunaíma about a mythical, “characterless hero” was his best-known book. Among his final works is the libretto for a collectivist and anti-capitalist opera called Café (Coffee).

Bibliography

Brecht, Bertolt (1965). The Messingkauf Dialogues. Translated by John Willett. London: Methuen

Brecht, Bertolt (1976). Poems 1913–1956. Edited by John Willett and Ralph Manheim. New York: Methuen.

Brecht, Bertolt (1996). Journals 1934–1955. Translated by Hugh Rorrison, edited by John Willett. New York: Routledge.

Brecht, Bertolt (2014). Brecht on Performance: Messingkauf and Modelbooks. Translated and edited by Tom Kuhn, Steve Giles and Marc Silberman. London: Bloomsbury Methuen.

Brecht, Bertolt (2015). Brecht on Theatre. 3rd edition. Edited by Marc Silberman, Steve Giles and Tom Kuhn. London: Bloomsbury Methuen.

Brecht, Bertolt (2019). The Collected Poems. Translated and edited by Tom Kuhn and David Constantine. New York: Norton.

Pasta Jr., José Antonio (2010). Trabalho de Brecht: breve introdução ao estudo de uma classicidade contemporânea. 2a ed. São Paulo: Duas Cidades; Editora 34.

[Appears in the Portuguese original in: Moringa Artes do Espetáculo, 14.1 (Jan-June 2023): 226-248]

[Back to TABLE OF CONTENTS]

*********************************

Brecht and the Measure of Distances: An Interview with José Antonio Pasta Jr.

by Sérgio de Carvalho and Maria Eduarda Castro

This interview with José Antonio Pasta Jr. reevaluates his book Trabalho de Brecht (Brecht’s Work), one of the most important reflections on Brecht’s work ever written in Brazil. Based on his Master’s thesis, it was first published in 1986 and reissued in 2010. It is an unusual book, even when compared to the contemporary international bibliography of Brecht scholarship, and it is certainly the most important written in Portuguese about Brecht, comparable only to Anatol Rosenfeld’s essays. Its original approach is that of “classicity,” an aspect that has only been hinted at or sketched by the likes of Walter Benjamin, Jean-Paul Sartre, Hans Mayer, and Anatol Rosenfeld. According to Pasta, Brechtian classicity is not produced as an aesthetic value referenced in the past, but rather as a construction that reinvents tradition to push toward the future. Thus, the book takes up and broadens the Brechtian concept of theatrical work in order to use it as a reference for the possibilities of critical art in a peripheral country like Brazil.

Below we ask José Antonio Pasta Jr. to comment on some of the central themes of his remarkable book. Our interest was in the current state of affairs, not only that of Brecht today, but also that of Pasta’s critical methods in relation to the recent acceleration of the processes of cultural commodification under the conditions of Brazilian neo-fascism. The interview also produced an unprecedented observation about the style of another author, the critic Roberto Schwarz, with whom the work of José Antonio Pasta Jr. dialogues. Since in Brazil today both Pasta and Schwarz are the most inventive and acute readers of nineteenth-century writer Machado de Assis, it is no coincidence that they refer precisely to his dialectical form, to that of the greatest of Brazilian classics, which seems to be imprinted on the thinking and literary attitude of our interviewee.

Before we begin, we offer some biographical notes on important Brazilian scholars referred to in the course of the interview:

Anatol Rosenfeld (1912–1973) was a German-born critic and essayist who became an expert of theater aesthetics in Brazil. He studied philosophy in Berlin but with the rise of Nazism he had to leave the city before completing his Ph.D. in German Literature. He arrived in Brazil in 1937, where he initially worked as a farmer and traveling salesman, and later pursued a career as journalist and essayist. In the early 1960s he became a theater professor and had a significant influence on theater productions in the city of São Paulo. His book Brecht and the Epic Theater (1965) was a milestone in promoting Brecht’s theories and the study of literary genre theory.

Alfredo Bosi (1936–2021) was born in São Paulo, where he was a professor of Brazilian and Italian literature at the Universidade de São Paulo (USP). He distinguished himself as a historian and essayist and was one of those responsible for introducing and disseminating the Antonio Gramsci’s writings in Brazil. He took part in militant Catholic groups in Osasco and São Paulo, working as a professor and activist alongside Catholic pastoral workers. Finally, he became a member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters.

Antonio Candido (1918–2017) was one of the most influential literary critics in Brazil during the twentieth century. Born in Rio de Janeiro, he taught social sciences and Brazilian literature at the Universidade de São Paulo (USP) until 1978. Between 1964 and 1966, he also taught Brazilian Literature at the University of Paris. In 1968, he was a visiting professor of Comparative Literature at Yale University. His book Formação da literatura brasileira (Formation of Brazilian Literature) became one of the most important references for studying the relationship between art and society. In 1980 he participated in the founding of the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT or Workers’ Party).

Roberto Schwarz is one of the most inventive literary critics and theorists in Brazil. Many also consider him to be the most important Marxist practitioner in the tradition of the Frankfurt School writing anywhere in the world today. He was born in Vienna in 1938 and emigrated with his family to Brazil in 1939. He studied social sciences at the Universidade de São Paulo (USP), obtained an MA from Yale University, and completed his Ph.D. at the University of Paris III, Sorbonne. He taught literary theory at USP and Unicamp. He is also an emeritus professor at the University of Liverpool (UK). He devoted a large part of his studies to the work of Machado de Assis. His books To the Victor the Potatoes! (Brill, 2019), Two Girls and Other Essays (Verso, 2012), A Master on the Periphery of Capitalism: Machado de Assis (Duke UP, 2001) can be found in English, and the last has also been translated into German.

Maria Eduarda Castro and Sérgio de Carvalho: In your book Trabalho de Brecht you analyze a classical attitude in Brecht’s work. This classicizing project is linked to the collective perspective of a work that “is not complete in itself – in its vision of the world” (p. 26) and seeks to survive its transformations. Could you tell us a bit about the dimensions of Brecht’s classicity that operates as political action from a socialist perspective? Also explain, if possible, why you chose such an unusual analytical angle at the historical moment in which you produced your work.

José Antonio Pasta Jr.: In Trabalho de Brecht the words “classic” and “classicity” (to which I have added “contemporary”) bring together a whole bundle of aspects of Brecht’s production, aspects for which they constitute a kind of common denominator. Thus, they are more than metaphors because they have (or I hope they have) descriptive value in relation to the work’s configurations, its genesis, its values, its reception, etc. In your question, you already associate Brecht’s “classicizing project with the collective perspective” of his work, which is right, insofar as the collective dimension, as well as other dimensions, does indeed take on a classical character. Like the “classics” of antiquity and even those that came later (think of Racine, for example), Brecht has a collective “ideology,” as well as a method and a social and political plan that is collectively determined. In a way, he “leaps” over the individualism of the nineteenth century, toward these classical or classicist matrices, which function by displaying the (collective) conventions with which they operate and put into play a “truth” of the polis, that is, politics, in the first sense. So, is Brecht identical to the classics? Of course not, because each of those “classical” traits I mentioned is present in him, but distanced: the collective is not only the presupposition of the play, but also becomes its mode of production and staging. The “truth” of the polis is also there, but it is not given, it is not based on religion or myth, it is at stake in the clashes of class struggle. That is the context in which it will have to be produced – collectively, let’s say, in the relationship between the stage and the audience, which is called upon to collaborate. The conventions that the plays display anti-naturalistically are both inherited and created ad hoc, and in both cases distanced, exposed as such, and so on. Hence, “contemporary classicity,” “fighting classicism,” non-traditionalist uses of tradition. If you don’t want to believe me, you don’t have to, but at least believe Sartre, whose words on the relationship between the collective and classicity in Brecht I’ve essentially reproduced here, without warning. By the way, when I wrote Trabalho de Brecht, I didn’t know this text by Sartre, “Brecht and the Classics” (Sartre 1999). In fact, hardly anyone knew it because it was lost, so to speak, if I’m not mistaken in the playbill of a play by Brecht performed in Paris by the Berliner Ensemble, in their celebrated performances in that city in the mid-1950s.

The same goes for the unity of the play, the economy of means, the containment of emotions (not the elimination of them), the model dimension, the sense of duration – all these “classic” traits are present in Brecht and distanced in him. Explaining them one by one would be tantamount to reproducing the work here, which wouldn’t be a bad thing, because I could take the opportunity to add what was missing, fix what was amiss, eliminate what is wrong, etc. Be that as it may, these are all eminently classical traits subjected in Brecht to the “re-functionalization” (Umfunktionieren) established by Benjamin as the key to Brecht’s relationship with tradition and the status quo in general.

You’ve noticed, of course, that I’ve been insisting on the idea of distancing, but it’s not for nothing. It is, at the same time, a central aspect of Brecht’s classicity and the device that allows him to approach the classics while distancing himself from them. Everyone remembers the classicist commandment of distancing (éloignement). It’s no coincidence that Benjamin went straight to the idea of distance when he first saw Brecht’s “classical” dimension. Commenting on Brecht’s 1934 satirical Threepenny Novel, Benjamin wrote at the end of his review: “It was this distance that posterity always appropriated when it declared a writer a classic” (Benjamin 2002, p. 448-49).

Now, approaching and simultaneously distancing oneself from something, which is what distancing does in Brecht, is more than just opening up space for contemplation and reflection (which is what he also wants), it is above all subjecting every piece of information to the regime of contradiction, in other words, to the possibility of it being transformed. In Brecht, distancing is nothing other than contradiction in action, which has enormous scope, runs through his entire oeuvre, and therefore lends itself poorly to the reductions to which it is often subjected.