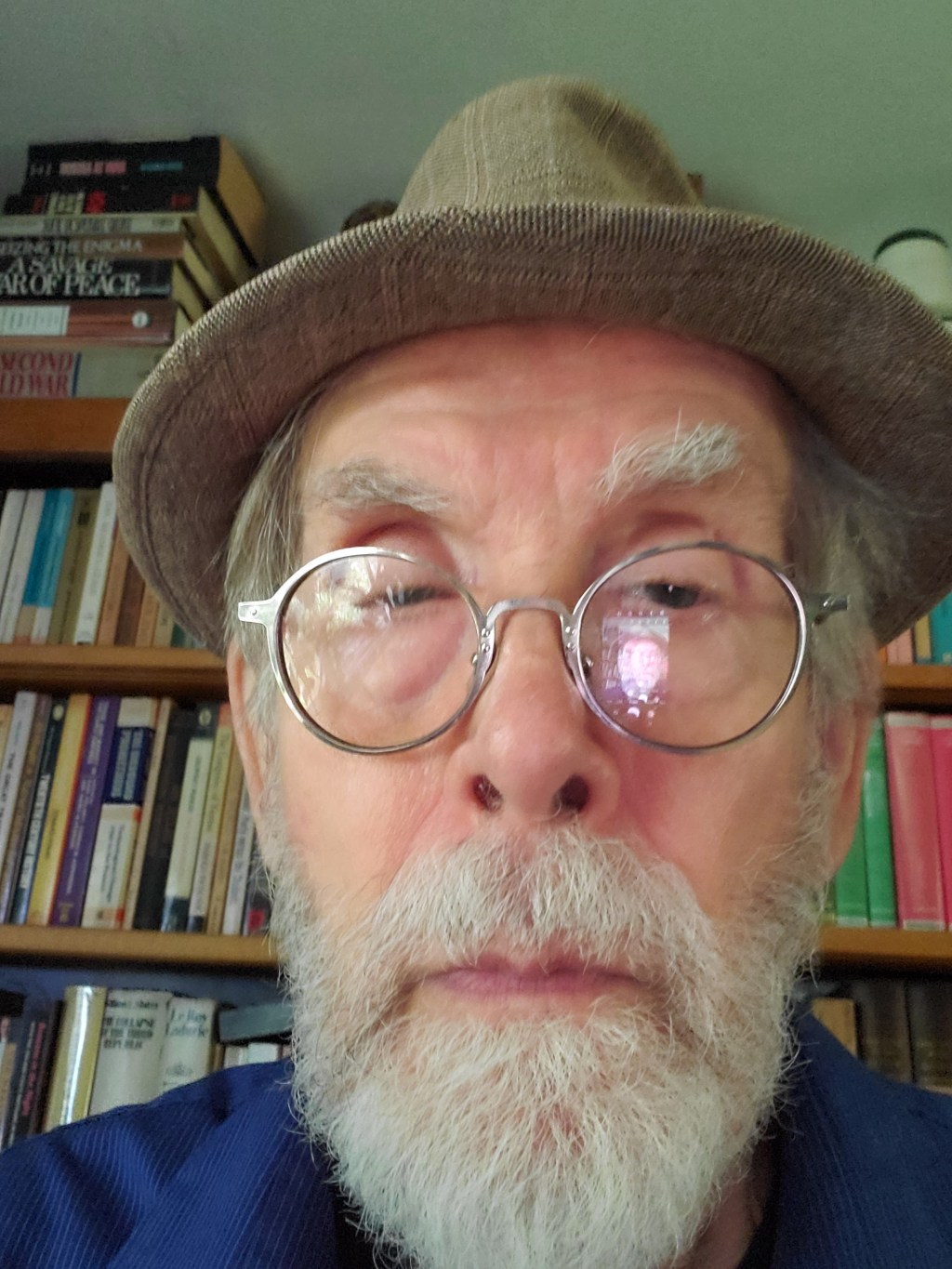

At E-CIBS we are always interested in political and emancipatory theater. That’s why we invited our friend David Simmons to talk with us about some of the interesting things he’s doing in these areas and the present challenges he sees. David is the president, director, producer, and sometimes writer at Fermat’s Last Theater based in Madison, Wisconsin.

AS: David, thank you so much for sitting down with us. Can you tell us a little about your background and how you became involved with Fermat’s?

DS: Well, hang on, as this will go off in a couple of directions, which, I hope, will converge and bring us up to the fraught present. I went to college from 1966-70 and those years saw major cultural and political shifts in many parts of our society. I was early on very opposed to the Vietnam war and I wish I could say that I was a leader in organizations trying to stop the war, but I was but a foot solider in the anti-war army. The stupidity of that war is perhaps rivaled only by the US invasion of Iraq in search of non-existent weapons of mass destruction, the echo of which we are seeing today in Gaza and Lebanon.

Like many people radicalized by Vietnam, I looked in the early and mid-1970’s to the labor movement as a possible source of political change. So for about ten years I was the lead organizer of a coalition of unions and medical professionals in Chicago trying to improve health and safety conditions for industrial workers. At some point I realized that if I wanted to really make a difference I needed to work inside the labor movement, and so I got a job at a Westinghouse Electric factory. That plant was organized by the United Electrical Workers (UE), one of the eleven “communist dominated” unions expelled from the CIO in 1949, and the only one to survive the Red Scare of the era. The UE was (and is) a militant and democratic union and I learned a great deal from its members and leaders. The fault in my (and others’) logic of course was that deindustrialization was about to hollow out the manufacturing sector of the US economy, and indeed, Westinghouse announced the closing of the plant and the movement of the work first to North Carolina and later to Mexico. Like many others, we waged, and lost, a bitter plant closing fight. But our union contract had a provision for worker retraining, and so I went to a community college and learned electronics, then got a job in a high tech, non-union factory in the western suburbs of Chicago. The union campaign there never really got going but I learned a set of skills that enabled me to get a job as a computer systems admin. In 1992 we – my wife and two sons – moved to Madison where I got a tech job with the University of Wisconsin. Now, many years later – two generations really – it is gratifying to see the new wave of organizing in all kinds of sectors of the economy.

AS: What can you tell us about Fermat’s mission and its founding?

DS: There is in Madison a youth Shakespeare program (Young Shakespeare Players), and our younger son was very involved with this group and I watched a great deal of Shakespeare from 2003 to 2010 or so. And there was a group of adults who also staged very amateur Shakespeare scenes and later full plays, and I was involved with that group, and played Falstaff in Henry IV Part I, which is more fun than any adult should be allowed to have.

There was a cohort of very talented kids who were a bit older than my son and who had aged out of the program and were in theater programs at various universities but who were home in Madison for the summers.

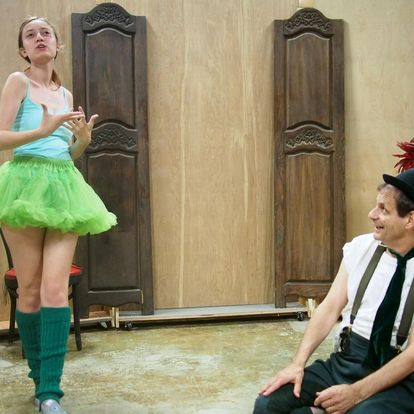

I had always wanted to stage Merchant of Venice and so I gathered this group of college students, and a few adults, and we rehearsed and staged this play in 2013 to very strong reviews. The next summer it was Troilus & Cressida, and again it was a big success. Both of course deal with contentious issues – antisemitism for MoV and gender politics with T&C. Year three saw Miss Julie and year four our original adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial.

AS: E-CIBS published a review of your production of Mother Courage Alone, in 2018 and you have also worked on something you called “The Brecht Project.” Please, tell us more about these.

DS: Our first two directors and lead actress had moved to Chicago by the end of year three. And while The Trial was popular, I had hired a director I had not worked with before and who I felt cheapened the message and darkness of the play and diverged widely from what I believe was a very strong script.

We had made the decision to become a free theater with Miss Julie, while the expenses of the summer shows were growing ever larger. The next play I wanted to do was Mother Courage and Her Children, a play that has twenty-six named characters and runs well over three hours. So, I decided to do a radical adaption of the play – one actress, one narrator, one musician, and it would be called Mother Courage Alone. The play of course is under copyright and Marc Silberman, the UW Professor of German and Brecht scholar, put me in touch with the US lawyer who represents the Brecht estate in this country. Not surprisingly he found this proposal ‘highly unusual’ or words to that effect. After a slow motion exchange of emails and phone calls to his office, he sent me a five page contract (in triplicate) which I signed and returned. To this day I have no idea what it meant, other than granting us no license to do anything other than this adaptation. I had already set about writing a script and often despaired as I tried to remove large chunks of the text from each scene and keep one or two of the verses of the many songs. So, I began again and tried to find the core of each scene and then add back in just enough dialogue for it to make sense and be true to the original. It ran just about an hour and we staged it (I did build a wagon!) in an art gallery space and then on the UW-Madison campus. We did the show as a reading this past spring. The Brecht Project followed that first Mother Courage Alone with two workshops that were a mélange of scenes, poems and songs, one called Singing in the Dark Times and A Voice for the Voiceless. I still have plans for others – one around the idea of struggle, to be called Into the Ring: Twelve Rounds with Bertolt Brecht, and to set it in a boxing ring. Other things (including the pandemic) have delayed that, but it is still on my bucket list. We did work parts of Brecht’s famous essay Five Difficulties in Writing the Truth into our documentary show about the White Rose Group, and it is really a foundational document for me.

(Click the photos above for slideshow.)

AS: Prior to these projects, what experiences did you have with Brecht? Do you recall when you were first introduced to his works and the impressions you had?

DS: In college there was a week-long series of lectures, concerts and theater about the culture and politics of Weimar Germany, culminating in a performance of Mother Courage and Her Children (why this and not Threepenny Opera I don’t know). But the lecture on Brecht’s life and the performance really stuck with me. A few years later I read The Threepenny Novel and was always recommending Brecht’s poem “Questions from a Worker who Reads” to friends. The use of art as a political weapon appealed to me very much.

Understand that I do not have much in the way of formal theater training. There are bad things about that and maybe some good. I certainly view theater through a different lens than most directors/producers. I am not satisfied to just get a script from Samuel French and stage it.

AS: I see that you’re attracted to documentary theater and working with historical material. What are some of your productions that fall into this category and why is documentary theater so central to what you do?

DS: Faulkner’s maxim that the past isn’t over, it isn’t even past, resonates strongly with me. Our next work, No Regrets! Albert Camus and Edith Piaf in the French Resistance (October 26 & 27) asks what choices people made in German occupied France and why, and what were the consequences of those choices. Some say fascism is on the ballot in the US in November and I would not disagree.

There is an astonishing chamber opera, My Lai with the Kronos Quartet, a baritone, and a Vietnamese musician Van-Ahn Vanessa Vo. A film about the opera and the massacre were screened at the Wisconsin Historical Society this past spring and people are working to restage the opera itself on campus next year, the 50th anniversary of the end of the war. I was speaking with a history professor who teaches the war, and he told me that to this generation of students, Vietnam is as distant to them as the so-called Great War was for us. That is mind blowing! When Biden expressed shock at the collapse of Kabul to the Taliban and said, “Everyone thought the Afghan army would hold out for six months” I was waving my hand at the computer saying “Not me!” – I’ve seen this movie before – Saigon in May of 1975. You want soldiers to risk their lives every day for six months so rich people can get themselves and their money out of the country? Not going to happen. People really don’t know the history that shapes their lives, and documentary theater is a way to get that conversation started. And Brecht’s theater demands that people think as well as feel.

AS: Fermat’s is a free theater. Why is it free and how do you keep it going financially?

DS: Being a political theater, in my mind, mandates that we be a free theater. A lot of our work is about people who have had no money. Our Joe Hill – Alive as You and Me – has been performed seven times around the country and we have more bookings in the works. Framed on a phony murder charge, Joe wrote his will in pencil on a piece of scrap paper (and of course in verse), and it begins, “My will is easy to decide/for there is nothing to divide …” He was penniless and had only the clothes on this back. Truly, Joe ain’t never died, as the song goes – and I don’t want him to show up at a performance about his life and not have the price of admission.

We did a dramatic reading of the letters of Vincent van Gogh to his brother Theo. Each letter begins with thanks for the money Theo sent him (he had no income of his own and never sold a painting) and ends with an appeal for more. A couple of years ago van Gogh’s painting, Cypresses with Olive Grove, sold at auction for $117 million dollars. Am I the only one to see a problem with this?

Secondly, a lot of the music (jazz/classical/opera) that I want to see is beyond my means – $20 I can handle, $30 is a real stretch, and more than that is not possible. And ticket prices for theater for equity shows range from about $40 to $100. We don’t want to price people, especially young people, out of seeing our work.

Finally, and most importantly, we don’t want to ever make the calculation about what we stage to be based on how many tickets we think we might sell. Two summers ago we did an evening of Kafka’s parables – strange and puzzling they are. I was hoping for 25 people, we got 55 and the audience did have a kind of Goth element to it, but I’m fine with that. I suspect those people are not regular theater goers. All the better.

How do we make it work? With great difficulty! We do have a core of patrons who contribute generously and we get small grants from public arts programs. Fun fact – Wisconsin is always 49th or 50th in the amount it spends per capita on the arts. I think it’s about 34 cents per person. Minnesota spends more than $7 per capita because they have a provision in state law that sets aside 1% of revenue for the arts. We do also ask for free will donations after the show and tell people that they are not paying for the show they just saw but helping to fund the next one. And we do pay our performers (modest amounts) and have all the expenses any organization has – venue rental, printing, graphic designers to pay, etc. And there is a Donate button on our website.

AS: On your website, it says that Fermat’s is dedicated to radical truths and (in the Brechtian spirit) it presents itself in many ways as a socially transformative theater. What do you see as the major challenges for such a theater today and what are some of the things you’re doing to try to overcome them?

DS: I think it means really digging deep into history and not letting ideology get in the way of what really happened and why. I’m talking here about documentary theater. I have gotten some grief from friends about featuring Albert Camus (and Edith Piaf) in our upcoming show, because Camus was (later) “wrong” about Algeria (and Vietnam for that matter). Camus tried to find a middle path on the Algerian civil war and found himself all alone there. He had broken with Sartre over this and his book The Rebel. He had no illusions about Stalin when much of the left in France (and elsewhere) were saying nothing about what we now call the Gulag. Many on the left said that criticism of the USSR was providing aid and comfort to the imperialism of the US. Stale, old, boring history, except that what is happening in Gaza/Palestine/Israel/Lebanon is fraught with complicated, dangerous questions – why and when do universities send in the cops? Is that the way to engage with those whom are you supposed to be educating? Did the university presidents visit the encampments?

The work of theater is to make truth anew. I think the most radical play I have read in the last year is Prometheus Bound, written in fifth century BCE Athens. Old can mean new! If I can paraphrase a character from Shakespeare, “There is nothing good or bad but staging makes it so”

The challenge for theater is to find an audience, a serious audience, and get them out of their comfort zone. We are competing with social media, television, streaming video and film. All of those can discomfort an audience, but that’s the hard path and not often taken.

AS: What’s up next for you and for Fermat’s?

DS: We have the Camus/Piaf show on October 26/27 and it’s been great fun, and the cast are all amazing. I think it is going to be a stunning performance. We are still taking the Joe Hill show on the road, and Tom Kastle, the singer/storyteller who is the show (along with lots of projected images) will be in New Jersey in October. We are planning a similar kind of performance focused on the life and times (and execution) of the Irish revolutionary James Connolly. I am interested in staging some of the early Brecht agit-prop plays like The Mother, but have not figured out a way into them or know if I can find or train actors to make works immediate.

AS: David, thank you again for your time. Is there anything else you’d like the readers to know before we end?

DS: I am curious how many people get the joke in our name. Being in a university town it’s maybe more than a quarter. And all the stuff we do is very dark. If we were to choose a different name, it would have to be The Existential Dread Theater Company. Doing all this reading about the horrors of German occupied France, or the Soviet Union in the 1930’s, or Munich in 1943 takes its toll on me, and there is so much reading I want to do and never get to because I’m always researching for the next script. Note that I do not believe in metaphysical or disembodied evil – no, all the evil that is done in the world is done by people and we have to confront that. But if, at the end of one of our performances, you have the feeling that someone just kicked you in the stomach, or say to yourself, “I never thought of it that way,” we’ve done our job.

Thank you.