Edited by Jack Davis and Kristopher Imbrigotta; HTML, layout and editorial assistance by Karis Chapman, Truman State University.

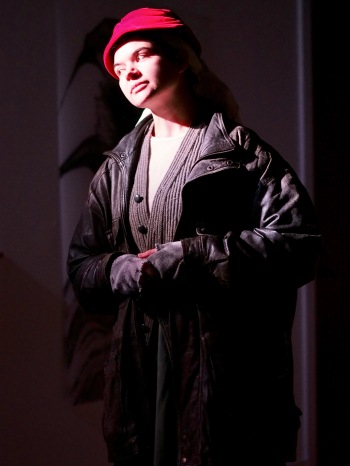

Greer DuBois as Mother Courage in Fermat’s Last Theater’s production of Mother Courage in Madison, Wisconsin [Photo: Hans Adler]

Interviews:

Essays and Reflections:

Urgency and Duration: Brecht’s ‘Unbesiegliche Inschrift’ (Benjamin Robinson)

Bertolt Brecht und die Literaturwissenschaft (Jost Hermand)

Brecht, Moreno and the Role-Playing Game (Evan Torner)

A Review of David Barnett’s Brecht in Practice Website (Bill Gelber)

Fatzer’s Failure: Individuality as Resistance (André Fischer)

Performance Reviews:

Beyond Baden-Baden: Part-Time Performers Explain Themselves – Korean Premier of Brecht’s Badener Lehrstück vom Einverständnis by Ensemble Theaterraum (Jan Creutzenberg)

Agreement and Disagreement: The Decision at Augsburg’s Brecht Festival 2017 (Anja Hartl)

Mother Courage Alone at Fermat’s Last Theater in Madison (Brandy E. Wilcox)

Conference and Workshop Reports:

22nd Annual Focus on German Studies Conference at the University of Cincinnati – “The ‘Epic’ Bertolt Brecht” (Ellen C. Chew and Seth Rodden)

Gisela E. Bahr – The Founding Mother of the International Brecht Society!

From left to right: Gisela Bahr, Helen Fehervary, Walfriede Schmitt (1986)

Marc Silberman and Helen Fehervary

Gisela Elise Bahr was one of the founding forces behind the International Brecht Society, the only woman among the “founding fathers,” and the cement that held the organization together, especially during its first decade. She launched the society’s newsletter “Communications from the International Brecht Society” in December 1971 (vol. 1, no. 1) as “a useful tool for the exchange of ideas and information pertinent to our ‘common cause,’” which she stated in her introductory editorial. She remained the editor, producing three issues each year, until May 1977 (vol. 6, no. 3), when she was elected IBS president and Henry J. Schmidt (Ohio State University) took over as editor. In his first editorial, he thanked Gisela for her “years of hard work devoted to maintaining and expanding the Society’s activities.” As IBS President, Bahr served for five years until 1982. Among her notable achievements were: representing the society at the opening of the Brecht-Zentrum der DDR on the occasion of Brecht’s 80th birthday (Brecht-Dialog 1978); maintaining contact with Gerhard Seidel at the Brecht-Archiv in Berlin; meeting in Summer 1981 with the GDR’s Deputy Minister of Culture, Klaus Höpke, to discuss cooperation with IBS; helping negotiate the new publishing contract with Wayne State University Press for the Brecht Yearbook in the early 1980s after Suhrkamp Verlag cancelled the publication with vol. 10; and initiating the project to obtain non-profit status for the organization. Bahr was at the center of the organization during these years and was largely responsible for the stability of its membership numbers.

Gisela Bahr was born in 1923 in Landsberg an der Warthe, then in Brandenburg and today in Poland, known now as Gorzów Wielkopolski (also the birthplace of Christa Wolf). She completed her PhD at New York University under the supervision of Volkmar Sander in 1966 with a dissertation on Brecht’s Im Dickicht der Städte, which led to her close friendship with Elisabeth Hauptmann while researching the background material at the Brecht-Archiv. This won her first prize for the best NYU dissertation of 1966. After completing her studies, she went on to teach at Rutgers University before joining the faculty in 1972 at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. There she chaired the Department of German, Russian, and East Asian Languages and finished her academic career as emerita professor of German in 1987.

As researcher/writer, Bahr produced important and excellent scholarship on Brecht, including three critical editions of Brecht plays with commentary and background material for Suhrkamp Verlag: Im Dickicht der Städte (1968), Die heilige Johanna der Schlachthöfe (1971), and Die Rundköpfe und die Spitzköpfe (1979). She also was a member of the editorial board of the IBS yearbook from 1972 until 1979 while it was published by Suhrkamp Verlag (vols. 2-9) and was one of the Brecht Yearbook editors under the imprint of Wayne State University Press (vols. 11-13). Here it should be noted that Bahr authored a book review in almost every one of the yearbook volumes, and she was the driving force behind the thematic volume on “Brecht, Women, and Politics” (BY 12/1985). As organizer and activist, she collaborated with her colleagues Claude Hill and Ralph Ley at Rutgers University to “stage” the second IBS congress there in April 1971. Among the featured guests she invited were John Willett from London, Eric Bentley, Erika Munk, Andrzej Wirth, and Carl Weber. And in 1986 at Miami University she hosted Walfriede Schmitt as artist-in-residence, a well-known theater and film actress from East Berlin who both directed and played the lead role in the Miami University theater department production of Brecht’s The Good Woman of Sezuan.

Gisela Bahr’s intellectual curiosity and energy took her beyond Brecht and the International Brecht Society. She was among the founding members of the Women in German organization and was responsible for its third conference in September 1978 at Miami University. She also published articles in the Women in German Yearbook and National Women’s Studies Association Journal. She traveled frequently to the GDR and then to the “Neue Bundesländer” where she cultivated her circle of relatives, friends, and acquaintances. She produced short super-8 films of her experiences, and conducted interviews and wrote about the changes in Germany. In her hometown of Oxford, Ohio, Bahr was a political activist both before and after she retired, involved in grass-roots initiatives focusing on peace and justice and the environment. Today, she still resides in Oxford and continues to enjoy reading the Brecht Yearbook, Communications from the IBS, and Brecht literature.

Interview with Samantha Van Der Merwe: The Caucasian Chalk Circle at the Shaking the Tree Theater in Portland, Oregon (October 6-November 4, 2017)

by Margaret Setje-Eilers

[See below for Margaret Setje-Eilers’ Review of The Caucasian Chalk Circle]

Margaret Setje-Eilers: Thank you for agreeing to meet with me today, Samantha. I’m so glad you produced Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle in Portland. It was tremendous fun and your staging had lots of surprises. How do you feel about this production?

Samantha Van Der Merwe: (laughs) It’s been a wild ride. The play feels like it had three parts that had to come together in the end: the movement, the singing, and the story. It was an interesting process. I followed my intuition about how to piece those three elements together, and I think we went about it in the right way.

MSE: How did you go about it?

SVDM: We focused on the singing first because the singing feels like the glue that holds the whole story together. I felt like I wanted the actors to be really sure about where they were musically, and it was always something that we could build on if we established it first. And also, it’s a large part of the narrative, so it guides you to where you’re going. And then the movement for me was huge. I am a lover of movement in theater, so the fact that we were doing it in a circle felt like we were creating shapes in space with the actors. I wanted the audience to feel that movement around them and in front of them, and then I felt that it was really important for the actors to know where their bodies were in space first, kind of like a dance, like you would learn the steps to a dance.

MSE: I’m glad you said that. My first thoughts were that it was like a ballet with song and text.

SVDM: (laughs) And I think the question was: were we deepening enough into character, were we understanding the scenes as they happened in these little pockets between all the movement? But I think as a natural consequence of repetition and coming back to the scenes each time, the characters settled. The impulse was to go over the top with character, which is always unsettling for actors and directors because you want actors to be truthful, but it seemed like Brecht demanded of us that we push over the top.

MSE: You brought out the extremely comic situations very well. That was fun for everybody.

SVDM: It’s fun for everybody because it is a big story. He’s making you tackle – and I think it can feel overwhelming – he’s making you tackle this epic world event. It feels like a world event, even though it is concentrated down to a certain country or a certain city. He is making us tackle so many ideas politically that if we don’t allow ourselves to enjoy these moments of comedy, I think it would be too overwhelming.

MSE: Certainly then, it would not be easy to sit for three hours without the humor and the playfulness, but as it was, the time went so quickly. I think no one wanted it to end. And anyway, Brecht wanted to entertain the audience and to make people think critically, so he worked in both directions. Congratulations on achieving that combination. How did you get into what I would call a theater aesthetic of dance? I read that you were first a visual artist. How did that happen? How did you get from painting to this extreme sense of motion and space?

SVDM: Well, I think it started in my childhood. My mom had been a ballet dancer and she took me to the ballet all the time. And her mom before her had been a ballet dancer. Actually, my grandmother was from Latvia and had moved to South Africa just before the Iron Curtain came down in Russia. She had wanted my mom to be a professional ballet dancer, and my mom chose to be a graphic designer. So, I think that this tradition of taking ballet classes as a child was kind of instilled into me. I took ballet classes from the age of six to thirteen. When I was thirteen my teacher said to me, I think you should try drama, because I was very dramatic. I always got the character parts. I wasn’t going to be a dancer. I just don’t have a dancer’s body, I’m not skinny and long. That is when I shifted from dance to theater. I think I have always appreciated dance. I actually studied theater all through high school, privately, and I wrote and directed my own plays in high school. So, it was always there. I think that after I left high school is when I felt that I had to make a choice between visual art and theater. For a while I chose visual art, but theater always kept pulling at me.

MSE: The visual art, that was a question I had right away because you just had four chalkboards around the large circle of chairs. There was little visual artwork in the sense of a painted set, other than the titles of the acts the actors wrote on the boards. That made me realize it had the classical five-act dramatic structure. I am not sure I noticed that in the production I saw in Berlin. You didn’t use visual art as painted sets, but you did use a lot of moving visual art.

SVDM: I think that’s it. I think for me usually an idea comes really strong and clear when I read a play. And for this one, it felt like the visual for me was the actors and their bodies, creating worlds in space. I really love the challenge set down, the gauntlet set down by Brecht: Let’s not pretend; let’s not be seduced by the illusion; let’s know that we are in a theater having a story told to us because then it breaks it down into the elemental building blocks of storytelling. It is a huge challenge of how to create a world in space with nothing other than a few sticks.

MSE: And just a couple pieces of fabric, some brown and some bright, to take us into these worlds. I noticed of course right away that there were two actors playing the child – if you count the baby in the basket as an actor.

SVDM: Did you know that the baby was a loaf of bread? In a talk-back with a group of students, the teacher said she loved that the baby was a loaf of bread because of its symbolism as an essence of nourishment, and that bread smells good like a baby does.

MSE: (laughs) A loaf of bread? I couldn’t exactly see into the basket, and I knew it wasn’t a real live baby, but that is most wonderful to hear. Theoretically then, the baby and the boy, that is the situation that Brecht was eager to create, the actor looking at himself playing the part. So, that’s what you did with the baby and this adorable boy who remained quite aloof and objective. Can you tell me more about that?

SVDM: Yes, when I read it, I had known that some companies had used a puppet as the child or I think used a really young child, because he is obviously younger, and I wanted to explore this idea of having the child as witness. Because the question that Brecht lays down to us is so powerful, about the question of possession, ownership. And if we always have a child on the outskirts as witness then we are held even more accountable to be objective in our decision as audience about who should be the rightful owner. Also, just this innocence of a child observing the action, when we talk about the land and the precious world that we fight over so often, he is just so symbolic for me of the future. To have a child in the audience is a very powerful symbol for us, to always know that he is watching and taking very seriously who will be his guardian.

Samie Pfeifer as Grusha, Will Sievertsen as Michael with baby basket, Clifton Holznagel as Singer [Photo: Gary Norman]

SVDM: Yes. And the interesting thing is that it came to me as an impulse, and I wasn’t sure if it was going to work, so I had about a three- or four-hour workshop with the actors. And I said to them, we are going to test out this idea of whether we can use an eleven-year old boy. The minute we started playing in the room and added the child in to the scene – we worked on the scene when Grusha at first found him and decided to come back and look at the child – I knew, just seeing him there and the way it made me feel, I knew that it was going to work. It was quite a delightful discovery.

MSE: He remained so poker-faced and aloof, I think Brecht would have loved to watch that. He was so intensely and objectively watching and observing, and not participating. How did you get that to happen?

SVDM: I’ve worked with Will Sievertsen before, so I know what he is capable of. With this play in general, I feel that a lot of the actors needed a very light touch direction-wise. I really just wanted to bring out the natural qualities of their personalities. It is a very natural state of being for Will. If you think of his experience as a young actor in the room, just watching older actors play like that, it’s probably very true to the experience he is having. And then he is a good representative of the audience. He gets to representat our thoughts and feelings in a way. He joins us in that. Also, this lovely framing device of the family. I really imagined that the goat farmers, the Rosa Luxemburg collective, were a family with the traditional head of household and then the other ones were this younger group, the Galinsk, these young cooperative farmers who wanted to have a commune together. I loved the conflict and the opposite feel of those two groups. So, if you just look at him as the youngest of this very traditional patriarchal family that is going to change, that will not do the same as has been done before him, then he is also a great character. If you just look at his prologue character observing the story and what he will do in the future and how he will change, it’s also a good angle to look at it from.

Will Sievertsen as Michael [Photo: Gary Norman]

SVDM: It is a playground for children, for the future. He says I’ll turn it into a playground and I will call it Azdak’s Garden, which to me feels like two things. It is very like the Garden of Eden, right? He is trying to create this utopia. Brecht is posing the idea of utopia to us at the beginning and how it could be easy enough for two groups to talk thoughtfully about a piece of land, rather than fight over it. And then we obviously see the battle over this child take place, and then we see it come to the utopian ideal of this Garden of Eden idea. It also reminds me a lot of Oscar Wilde’s The Selfish Giant, where he won’t let the children in and then eventually he has this experience where he feels empathy for one child, the Christ Child, which Brecht would have hated – I love how he is always subverting religion – but in the end the selfish giant opens up his garden to the children. It’s got the same sort of quality.

MSE: It comes down to who is beneficial for what, what kind of relationship is good for both sides, how can something be used beneficially. It ends with the land going to the people who want the irrigated fruit trees. That brings me to ask you about the name of your theater, “Shaking the Tree Theater.” Where did that come from? Not from this play, I imagine, but it fits there.

SVDM: (laughs) In my very early days of dreaming about what I would do with my future, I was in my painting phase and I had a flea-market stall. I envisioned a shop that I would possibly call The Bohdi Tree, and it would have a large wooden tree in the center. So, I guess the original vision was a clue of what would come to be, and I guess there is an imaginary tree in the center. I found “Shaking the Tree” from a German fairy tale, Mother Holle. She lives in the underworld and she makes snow when she shakes out her bed. [In the story,] [o]ne of the tasks that the young girl has to do when she falls down the well is to shake the tree with the golden apples, she has to milk the cows, and she has to pull the bread out of the oven. And after doing his work on a daily basis and helping Mother Holle in the world below, she is rewarded with this beautiful golden dress, so the story goes. For me, that work is your deep soul work, your artistic work. If you do it diligently, you are rewarded with these golden apples. I just love that idea that the tree is always laden with fruit. All you have to do is listen to the impulses from your soul, do the work that really matters, and the bounty will follow.

MSE: What a surprising and lovely answer. It also works so well with the prologue, the conflict about the goat herders and the fruit tree farmers.

SVDM: That’s true! (laughs)

MSE: I also thought about the act of shaking something up, in a critical way. A critical stance.

SVDM: It’s a very active word, a very active phrase, to shake something.

MSE: Would you say your theater has a critical objective?

SVDM: Yes, as a woman I am always interested in taking a classical work and putting it out there in my perspective, which is not going to look the same as it has looked before, hopefully. And I am also interested in the work of women playwrights. So, I don’t know if that is very revolutionary, but certainly there is this idea of doing something my way, despite the society I live in, despite the many restrictions that are sometimes put on women, to create my own utopian little corner of the world, where I get to do things the way that feels most right for me and also brings people along for the journey.

MSE: You have so many very young actors. In Brecht’s theater, the Berlin Ensemble, and all over Germany, theater is very heavily subsidized. Most of the actors are under contracts that are renewed if they do good work. Your ensemble for this play is so integrated, in sync, like one body moving with many different appendices on this circular stage. It breaks my heart to think that this group is not going to be together again.

SVDM: (laughs) Well, I’ve pondered this idea a lot. Should I have a permanent ensemble or should I work with a bunch of different people? Each play has its own personality and has its own needs, and for this play in particular, I found a whole group of people that I hadn’t worked with. It just shows you what’s possible when you focus on building an ensemble and what it takes to make them bond with each other. I usually have a six-week rehearsal period with a seventh week for tech. I felt for this show I would have loved an even longer one because, if this is what they accomplished under this time constraint, can you imagine what we could have done with a few more weeks?

MSE: I was happy. I didn’t need a few more weeks, but maybe the director did.

SVDM: Well, I’m very interested right now in how to build ensembles with strangers, with people who haven’t worked together. I feel like it is the strength of a piece like this. What do I need to do as a director to generate that work between them and to build that trust? Obviously, our process had its ups and downs and it was crazy in all the ways that a process could be.

MSE: I guess this is the right moment to ask what went wrong, if anything did.

SVDM: (laughs) Well, we lost an actor a week before the show opened who couldn’t appreciate my style of directing and didn’t trust that we were doing right by Brecht. It was clear that if we were going to continue to go down that path we were not going to have a successful show. It was something that hasn’t happened to me before as a director and it was very challenging, extremely challenging. And you know what? It was meant to happen. I always say to myself when I am in a production that I would rather go all-out and put on a huge failure than play it safe and put on a mediocre piece of theater. So, I had to reassure the actors that I wasn’t giving up, that I didn’t know what was going to happen in the next twenty-four hours, but that I was going to figure it out and I wanted them to know that I believed in them, and I believed in the piece. Miraculously, we found an actor to take on all his bit parts in the first act: Heath Koerschgen, who was the old man, the Governor. And then Clifton Holznagel, the Singer, took on the role of Azdak. Clifton was meant to be Azdak. Clifton said to me when he sat down that morning to start studying the script, he felt the presence of Brecht really strongly. I did too that day. Oh, we have unlocked a gate here, where Brecht finally approves of the direction we are going in, and he is being benevolent with us. (laughs) And I understood something about what he was trying to say. He did not want Azdak to be what I imagined a judge to be. He wanted him to be the antithesis, the mischievous coyote-like character that Clifton so beautifully portrays. What I needed was Clifton’s willingness just to jump in and fail big.

MSE: That’s just what Beckett says: “Fail better.” But he didn’t fail at all. Clifton was already in the show? He was marvelous as Azdak.

Clifton Holznagel as Azdak [Photo: Gary Norman]

MSE: You mean as the narrator? But he was not the narrator-singer all the time, was he? Some lines that belonged to that role were delivered by other characters.

SVDM: Yes, especially when it came to singing some of the intros to some of the acts. Some actors like Briana Ratterman Trevithick would step in with the accordion. It happened musically, when we realized, oh these voices would be lovely, we added them to help Arkadi tell the story.

MSE: When Samie Pfeifer (Grusha) was leaving the theater, she told me that she and the actors had written the music. What part of the music did she write? It was exquisite and quite varied. The style is not at all like Paul Dessau’s music. How did it come to be?

SVDM: It was the most beautiful, organic process I have ever experienced. I haven’t ever done a musical before and I didn’t want to call this a musical because if I did, I think I wouldn’t have done it.

MSE: You could have called it a musical. Anyway, that’s what some audience members near me were saying.

SVDM: (laughs) We could, yes, absolutely. We took our first five rehearsals – we read through an act per rehearsal – and we sat and we shared the songs. And ahead of time, Clifton had been thinking about the narrator, the Singer’s songs, and Samie had been thinking about Grusha’s songs. Briana had been thinking about a few of the songs with her accordion. It was so wonderful because when we sat down and got to a song, it was very tentative at first, and someone said I’ve prepared something, would you like to hear this? We all said: “Sure!” Then they’d sing it and we would be blown away by it. And someone else would say, I’ve actually been thinking about this one, and then Jess, Jessica Tidd, who was the Corporal, had thought about a few of the songs too. It really was a group effort. Joellen Sweeney, who was our music director, listened to them, brought more voices in, and added harmony. She orchestrated it. It was just a beautiful process of a very cooperative effort.

MSE: That sounds like a thoroughly Brechtian way of working. The structure of his rehearsals was experimental: “Let’s just try it out.” You must have had his spirit floating around, saying, “Yes.”

SVDM: I think so. I was so happy to read that about him when we had our crisis – I am a director who says don’t ask me too much, just let me see it, and I will tell you if it doesn’t work. Let’s just do it. Get your brain out of the way. I know it doesn’t make any sense to be in a rotating house made of sticks. But just do it so I can see.

Rotating Hut [Photo: Gary Norman]

SVDM: Everything is supposed to come to Grusha, right? All these events come to her. If we had had a million-dollar budget, we would have had a rotating stage.

MSE: I don’t think I’ve ever seen that happen, at least in my theater experience in Berlin. If you are sitting behind an actor and you can’t see the action for a while, “tough luck.” You miss it. I guess it was always the element of surprise and ingenuity, which brings me to ask you more about the set. The current production of the play directed by Michael Thalheimer at the Berlin Ensemble has no set, and you practically had no set at all, but you created everything you needed with the bare minimum of bamboo poles, fabric, a couple of tables, a marvelous chair on wheels, and a little table on wheels. You took us to all sorts of places. And the bridge suddenly evolved before our eyes. How did you make that work?

SVDM: I think for me, and this is throughout my work, the audience is a huge partner in the imaginative realm. If I can suggest something and then have your imagination do the rest, it is better than anything I can create because we just know how to go there with our imagination. I don’t know what you are seeing, but it is much richer than any set I could paint. That’s the first thing. The second thing is the bridge. We had played with all sorts of materials in our initial workshop. I brought out sticks, I brought out fabric. I wanted to know what are the building blocks of these worlds that we want to create. The actors grabbed the fabric and we were testing it out in all sorts of ways. I remembered one thing they did from the workshop is that they had hooked the fabric over each other to make a net. When it came to rehearsing the bridge, I said, “Remember what we did with the fabric? I’ve got these pieces, let’s see what happens.” And they started playing with the fabric and they started bouncing off it. One actor would run at it and would bounce back. I basically just said to them, “Find out everything that this fabric can do when you hook it into a net like that. I want to know all its capabilities.” And in the playing and wondering about what its possibilities were, we came up with these wonderful moments and then we started having Samie walk across it and asked what if this happens, what if she falls through it. I wasn’t interested in a realistic interpretation of the bridge. I wanted to capture the essence of what it feels like to be teetering above a chasm. How does the audience come with us in feeling that precariousness?

Bridge with Samie Pfeifer as Grusha [Photo: Gary Norman]

SVDM: I think the bridge’s strength is in the time that the group took to explore it. We did it as a warmup for a whole number of rehearsals, and in the warmup and in their play, they discovered their boundaries within that structure. That’s the beauty of ensemble, getting a group together, not worrying about perfection, not worrying about [whether or not] this [is] a realistic bridge, not thinking ahead to product, just living in the play.

MSE: You know there is a history of critique of Brecht’s so-called “formalism” in the early years of the German Democratic Republic, particularly concerning his opera with Paul Dessau, “The Trial of Lucullus.” He supposedly swayed from the agenda of socialist realism and had moments that were more creative (and subversive) than the Ministry of Culture wanted.

SVDM: We have an inner culture ministry sometimes in the arts, where we believe it’s too silly or too childlike or not real enough. We have all these parameters that we set and I am just not interested in that at all because if we never burst through that thinking, we never realize what is on the other side and we just get to see mediocrity.

MSE: When you talk about going beyond parameters, a special moment comes to mind now with the marvelous actress who played the peasant woman in the trial about the cow and the ham (Luisa Sermol). How did you come up with the dance between Azdak and the peasant woman? Azdak follows the woman in a circle, trying to position his chair on wheels so that she will sit on it. But she leans on her table, wheeling it in the same direction and at the same speed as Azdak moves, so nothing happens. She does not sit down. Then one of the Kulak farmers shouts, “This is a three-hour show, get on with it!”

SVDM: (laughs) That is just a moment of theatrical beauty. In the spirit of clowning, we had to go to the clowning place, especially in act four. It feels to me like a lot of deep clown work. Clifton and Luisa discovered that, obviously, because she moved so slowly. I don’t know how it came up in the room, but it was something that we knew would work immediately, and it has become longer and longer (laughs). Actually, in the performance yesterday it went even longer, and it is just a beautiful moment because we are near to the end of the play, and we acknowledge that it is a long play, but yet we revel in this glorious clowning moment of trying to get Granny to sit.

MSE: You have such a knack for Brecht, [both] the instructional and the entertain[ing] [aspects]. Would you consider doing another of his plays? One that comes to mind with a lot of music and potential for movement and clowning is “The Threepenny Opera.” Your warehouse location would be an ideal setting. You could even do part of it outside as street theater and some inside your theater. And Luisa and Heath would make a great Peachum couple, the capitalist organizers of the beggars in London’s Soho district. It would be a very big challenge. It is really a musical and it would involve getting the rights to the music. Maybe there is a grant for that? You have the singing, acting, and comic material. I would like to see you do more Brecht.

SVDM: (laughs) You are throwing down the gauntlet? Brecht has been a great teacher for me. I always pick material that frightens me to death, that I am fifty percent sure that I can’t do. Then I do it. And I feel like I learned so much from him. Now that I understand what I am dealing with, it would be really interesting to take on another Brecht piece, knowing what I know and capitalizing on it and seeing how I can listen to his voice and express his thoughts even more. There is a reason why he is one of the greats in theater. He makes us think, he wakes us up, he presents us with raw theatricality. He really brings us down to the essence and the bones of storytelling, and at my heart, no matter how I am going to express myself in my life, I am a storyteller. I get him. I understand him, but I also feel like I am at the very tip of the iceberg. I will be a lifelong student of Brecht.

MSE: Excellent. Do you know the German word “Verfremdung?” “Estrangement,” and the German words “Verfremdung” or “Verfremdungseffekt” are now the accepted terms.

SVDM: Yes, because it is misleading to say alienation.

MSE: [It means ] [m]aking something seem unsettlingly unfamiliar, but taking you into a story that seems like something you don’t know, and bringing you out again into something that is very familiar. We as the audience realize that we can make changes in our familiar world, as unchangeable as it seems to us, just as the unfamiliar situation in the play has been changed, estranged. In your play, the concept of ownership changes into something else, a relationship of nurturing. You bring this across in so many ways in your production. Your actors also constantly break the fourth wall and establish ties with the audience. The groom’s mother (Luisa Sermol) passed a tray with wedding-funeral cakes and admonished the person next to me, “No more cakes for you!” Brecht has influenced so much of how theater is made that it is not immediately evident as Brechtian when a member of the audience becomes involved in some way. And the doubling of the baby and the young boy is a prime instance of estrangement. You are doing this so well.

SVDM: That’s why it felt so great to keep the actors on stage during the whole first act, just to have them retreat to the corners.

MSE: Some of the action also happened in the corners, at the table of the peasant couple. Every inch of space was used. Comments from the cast and music came from the corners and the edges, also the marvelous long bed appears from nowhere. You brought much more comedy into the play than I had expected. The Governor briefly seems to be Trump when he says he is draining the swamp, but you didn’t belabor or dwell on that. What kept you from making your production into an allegory of American politics today?

SVDM: A lot of directors want to set the play in a particular time and really drive home that we are dealing with a historical or current political situation. Certainly, in the prologue they like to tell us exactly where we are in place and time. I felt like I didn’t want to do that. As I told you after the show, Carlos is from Venezuela, and he related to the play because of what is happening in his country right now (Carlos Adrian Manzano as Fat Prince, Peasant Man, Dying Peasant, Lawyer). Many other cast members related in different ways, like Carla Hillier, who played Natella Abashwili, the Governor’s wife. Her family is from Estonia, so, from talking with her older family members, she is very familiar about the troubles that have happened in that small pocket of land. I’m from South Africa. And we are in troubled times right now in the United States. Most of us know what it feels like to have an unstable government. We can understand the universal nature of civil war or strife or corrupt politicians, no matter where we set the play. It feels nice to have a hodge-podge of people. I love that Heath invoked Trump because of course he is the “perfect” Governor, but he could be any governor throughout time. We could have picked from hundreds of different people in history. And as I said, my grandmother was from Latvia. She and my grandfather became atheists right after the Holocaust. So, it’s been our history, it is in our DNA, we understand it. I love that the place that Brecht picked was a real place, but it was also an imaginary place. And that to me – as a storyteller and lover of folk tales and fairy tales – is where he really hooked me.

MSE: I’m just remembering – I think it was the only time – that you invoked three different levels that gave a mountainous feeling. The violin music playing from the top of the wall structure around the stage and Grusha was up on a stand or pedestal before the bridge scene below. Your design situated us easily and abstractly into an imaginary location.

SVDM: And there is always this fear, especially because we are a small company, there is this fear, is it enough? The word “enough” always comes up. Are we doing enough to show place and time? The beautiful thing about Brecht is that he lets you off the hook a little bit because he wants you to embrace the bones of the place that you are in. He wants the audience to see everything. Usually I am trying to hide the stage manager away, so that the audience can’t see. But I loved that you could see the shadow of Natasha Stockem, the Stage Manager, up there working the lights, because I think that that is what he wanted. It is a wonderful invitation to use the space. With other actors in other shows, I am always talking about the warehouse. Let’s just embrace that we are in a warehouse, and the world of the play exists within the outer world of the warehouse. Let’s not try to hide the fact that we are making theater in a warehouse. Brecht really allowed me to do that, without apology. He wanted me to do that.

MSE: Exactly. You also worked with such simple things, like the long piece of blue fabric. First I thought it was a metaphor for the passage of time, or a symbol of time, as the actors carried across the stage in a bold diagonal. And suddenly this expanse of blue became the stream. It was marvelous. Was I wrong?

SVDM: No. It’s three things. It’s the passage of time made by these daily tasks that Grusha has to do in order to stay married to this awful peasant. It is the linen, and it is the stream. It is three things. And they are singing [that] as time went by, he faded. She could not see his image so clearly in the water.

MSE: That is really stunning, to see one piece of cloth serve so many purposes so close together. Right, and then she seemed to be washing the cloth, as the linen. That was remarkable. I think that might be your trademark.

SVDM: (laughs) Yes, I do love that. It’s my jam.

MSE: There was no time for any major costume changes. That was another layer of “Verfremdung” for me, because I had to figure out what role Clifton was playing when he wasn’t Azdak. That transported me to a different context. You used very subdued lighting, practically no make-up, and the costumes were muted browns and black. The few spots of color were all the more memorable because they stood out so intensely. The blue cloth of the stream and also the big blue-green bed. And of course, the bright dresses.

SVDM: That’s where I think my painting, my visual brain comes in, because I love color. And there are only some times in some plays, there are few places where you can make that statement. If you choose wisely, it can really pop and stand out in the audience’s mind. If you have too much of it, if it is everywhere, then that blue stream would have meant nothing to you. Originally, the fabric came out from under the bed (which is a beautiful turquoise color), and I wanted it to match the bed exactly, but once we decided to move the bed, which was a great decision, I realized the fabric had to come from somewhere else. It’s the same thing with the dresses, the scene with the dresses hooked my visual brain and I imagined all this colorful fabric and Natella being in a maze of fabric, and that for me, those little hooks are where I sign on visually, and then I have to get the rest of me on board.

MSE: Even in the dress scene, the women are sitting in a circle. And at other times some of the lines are delivered by actors walking around the circle, when they could have stood in one place or moved back and forth in the middle of the stage. This metaphor of circularity, and I guess inclusion, or even captivity, was so strong in what I have to call your dance, your production as an intricate ballet. Every moment where something could have been static, you had the actors move. Maybe not every moment, but almost always, and that made it a dance.

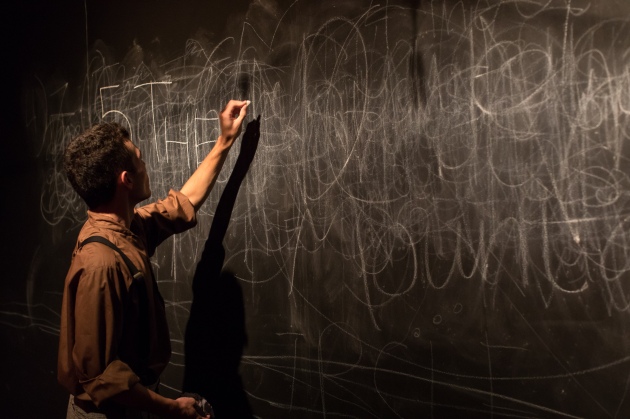

SVDM: That’s lovely. We talked about that idea. You know it’s hard to do theater in the round because someone is always going to get your back, so you have to change your position quite a bit. But also, if you look at the idea of shapes and patterns, making shapes within a circle, to me, this is a lot of what the play is about. Old wars that have come before us, the displacement of people. We are just moving in patterns. What I love about the chalk board is that we’ve written these chapters so many times now, and it feels to me, to see these old markings of the chapters, like it’s happened before and it will happen again, unless we make a conscious decision to be smarter about how we talk about the land and who has rightful ownership to it.

Chalkboard [Photo: Gary Norman]

SVDM: It feels like the inner workings of a clock in a way. Time is always moving. Do we repeat those patterns, or do we change?

MSE: Yes, how do we get out? There are dotted lines on the circle on your program, and the diagonals suggest that there is escape, there are paths out. Not in the circle that we saw drawn on the stage, though. Did you design the geometrical program cover?

SVDM: No, I shared images with the designer and told her what I was thinking and she came up with the image. We are tasked with listening to our intuition as artists. We are presented with an idea and we must intuit how we are going to express it. Everyone brings a piece of that full intuitive vision into life. And it would be different, depending on who the key players are.

MSE: Everything worked together, the circle of being trapped and the challenge to break out. Of course, someone eventually did pull the child out of the circle, but it was the unsuitable person, the biological mother. I want to ask just a couple more questions about the ensemble. Did your actors know about Brecht? How did you present him and what questions did they have?

SVDM: We had a lot of questions. A lot of people had learned about Brecht in college or have seen a production or been part of a production of Brecht when they were in college, so it is a distant memory and understanding. There are certain Brechtian ideas in the theater that we know about, but in a very general sense.

MSE: What, for example?

SVDM: Well, they knew about the alienation effect, which now has a new name, estrangement, about deconstructing everything, about breaking the fourth wall. There are a few basic ideas that people had. And probably, I am questioning, now looking back, I should have had a dramaturge. Sometimes I do and sometimes I don’t. When I want to learn a lot about it myself I do the dramaturgical work. I put pertinent information on a google document, and I shared it with the actors. It included important ideas about his background, and about the way Brecht wanted to make theater. We talked about the setting. I also would bring in material to read to them, when I felt like we had hit a block and we didn’t quite understand what we were dealing with, especially in acts four and five. It became very political with Azdak and we needed to understand the context of what was happening and what world events Brecht might have been referring to. Because he was a Marxist, I wondered if he was talking about the Russian Revolution. A lot of it was guesswork and some of it was, “Oh my gosh, I found this piece; here’s what I think he is talking about.” I feel like we were at a cursory level of understanding Brecht, doing our best to pull these very large political ideas into our story and understand the world we were working in. I hope that I gave the actors enough grounding. I hope I gave them enough understanding because the thing about The Caucasian Chalk Circle for me is that it’s a very simple story. On one hand you’ve got this lovely, simple folk tale, and so that part of my brain says, “Oh, I’ve got this.” I know how folk tales work. I read fairy tales all the time, I teach them, I know how this works. And then on the other hand, you have political corruption that feels more historically “real.” I am not a predominantly political person. My politics are personal politics. I hope we did it enough justice in our understanding of the world of the play.

MSE: It is a curious idea and a wonderful irony that Azdak, as the epitome of corruption in the court system, is actually on the side of the peasants and the poor, so that ends up being called the golden age of something almost like justice.

SVDM: I loved reading about Brecht, that he was anti-religion, that Azdak was his subversion of Christ. Brecht is always subverting things for us. To understand those layers, we had to dig deeper, and it happened quite late in the process for us, too. It didn’t all come at the beginning. We didn’t say, “Let’s learn everything we need to know at the start,” because it is such a huge endeavor. We had to tackle the play in layers. We had to work on the songs and the movement and then try to infuse knowledge into our brains so that we could deal with the scenes as honestly as possible.

MSE: You included practically every word. Here, in the program I just gave you of the production at the Berlin Ensemble directed by Manfred Karge, you can see that he did not do all the scenes. That makes your accomplishment even more remarkable. Your production is very true to the text. You know, you chose one of the very big Brechtian plays. He wrote many that are more compact.

SVDM: I know, I don’t know what I was thinking. I think I got hooked by Grusha’s story, and then I realized how much I had taken on after that.

MSE: I think it is possibly the only Brecht play with a happy ending. It’s dangerous to generalize, of course. Maybe that can be challenged, depending on what you call a happy ending. His plays usually don’t end that way, or they are cautiously optimistic.

SVDM: Yes, I have read that.

MSE: The main figure – often a woman – is often criticized for not “getting it,” but the audience is supposed to. Mother Courage, Saint Joan of the Stockyards, Arturo Ui. It is win-win for Grusha.

SVDM: And she is a sucker. She is the one who would normally be taken advantage of.

MSE: So, you chose an unusual play by Brecht. If I may, I also want to ask you who influenced you along the way. Which visual artists and people in theater would you not want to miss?

SVDM: Oh, now I am going to have to plumb my brain. I am trying to think of who I loved first and then go from there, as a young artist. Tennessee Williams was one of my first loves, and Sam Shepard. I love Frida Kahlo with all my heart. I love Caryl Churchill. Naomi Wallace, I discovered, is a very political writer. I must be more political than I let on. Who else? I love any abstract artist, like Picasso, just looking at Picasso and his journey. And Matisse. I have always loved Matisse. And then I love any great classic writers in literature, like Lewis Carroll. I love children’s stories. I love Clarissa Pinkola Estes who wrote Women Who Run with the Wolves. She’s a Jungian therapist who writes about myth and fairy tale from a very deep place. And Jung. I’m very influenced by Jung. And then theater-wise, it always has to be a strong story for me. Athol Fugard, a great South African playwright. William Kentridge – he is an amazing South African artist. He is one of the great theatrical/visual artists of our time.

MSE: What about what I call your “theater of choreography?” You have a style I haven’t seen before.

SVDM: I love Dario Fo; I love his work. It’s a very physical theater. I don’t follow dance groups as much as I could. I look at lots of images of dancers. I don’t know Martha Graham’s work enough to say that she is a person who influences me, but I admire her philosophy.

MSE: Your truly unusual style seems to come from your personal background with ballet and art. I would dare to say there were no pauses in the production. There were no breaks where we could have been sitting and waiting for something to happen. The action, the songs, and all the transitions and entrances worked. It was magical.

SVDM: The more I do it, the more I realize that I love to work with actors who can move well. I like to choreograph. I think I am choreographing.

MSE: Oh, you definitely are.

SVDM: Physicality is a very important piece of storytelling for me. But I think I am still on a journey of discovery about it. I know I ask a lot of the actors. It is a marathon every time they perform. They are constantly moving. It’s not for the faint of heart. The actors must be strong. But the presence of physicality throughout the story adds a life to the piece that I don’t think you can achieve otherwise. Without it, you would have what Peter Brook would call “deadly theater.” He is another huge influence. A master storyteller!

MSE: What you have achieved it is new for me and astounding. What would your dream be? How do you want to develop?

SVDM: I am in a phase of reimagining myself and what I want to do. I have always thought of the warehouse as my space, as a vehicle to do the plays that I want, in the way that I want to do them, with the people that I want to do them with. It affords me a great luxury of deciding what those things will be, rather than waiting for someone to hire me at a specific theater. I think my goal is to keep doing work that scares me, to keep working with material by great artists because they teach me so much about how to make theater. It is something that I could not learn in a lecture. I have to learn by doing. I have always learned by doing. And to just keep pushing what those boundaries of theater are, because I think we keep having to learn how to tell stories. You know we have this traditional theater model that we are trying to break all the time. We will always have it. I mean we will always have a proscenium stage. We will always have the actors on one side and the audience on the other. But for me, I want it to feel like an event. When I go to see a play, I want to be surrounded by it and immersed in it. I want it to harness my imagination and I want to feel something. Because it really is the soul of our society to be able to share stories and thoughts with each other, artistically. I don’t know if I want more than that. I would love to work all over the place, in different countries, but right now Portland is a fertile place to be working.

MSE: Or as a resident guest director at a university? Could you envision that? Although I wouldn’t want you to leave.

SVDM: That would be wonderful.

MSE: I want to mention that blocking in German is often called “Choreografie” and “Arrangement.” That fits well with your aesthetic, finding the essence of movement on stage.

SVDM: Well, I think some people are very auditory learners. They can hear words and it can invoke a whole bunch of images and thoughts within them. But I am not like that. For me, the picture that is made when two characters are speaking to each other is so important, where someone is in that dynamic says so much about the power structure between the two of them. It says so much about what is truly going on. And it supports the words so much. So, it has to be thought about, and once you have said it, it does become like the steps of a dance that need to be repeated because it is a big part of the storytelling. I might have just gone around in circles there (laughs).

MSE: Not at all. You are all about getting out of the comfort zone.

SVDM: It is scary doing pieces that have been done before and that people know because they always have something to compare it to, or they have an idea in their head of how it should be. So, there is always this fear that you will put it out there, and it will be wrong. I think we’ve got to let go of this idea of “wrong” because I don’t think there are rules in artmaking. And when we try to stick to rules, we get ourselves into trouble, in my mind.

MSE: Then the circle would have no dotted lines. Thank you so much and all the best for your next work, “Macbeth,” which I will be sure to see (February 16-March 17, 2018).

Urgency and Duration: Brecht’s ‘Unbesiegliche Inschrift’

by Benjamin Robinson, Indiana University

[Presented on the panel “Turning Points and Their Axes: Change and Resistance in Brecht and Company,” sponsored by the International Brecht Society at the 41st Annual Conference of the German Studies Association in Atlanta, Georgia, October 2017.]

How do singular statements about events negotiate the problem of time? Consider the sentence, “wow, look at that”—whatever it might do, it hardly qualifies as interesting. For it to give you information besides that of its formal semantics, you’d need to be in some perceptual relationship with its circumstance of initial utterance. There is nothing in its “that” which you could look up at your leisure—rather, you need to be right there, in proximity to the exclamation in order to perceive what it intends. And the whole problem with unique contexts is that the event that would give “that” meaning is an evanescent moment, a surprise, something unintelligible in light of normal expectations—in short, the context that would make the singular expression meaningful is itself lost to any perceptual fixation.

On the face of it, then, a lonely snowflake falling in summer, and the helpless cry pointing to it, would just as soon disappear from our minds as contribute to our meaning-making. Why not leave it at that? The answer is that we need the singular to survive—as much as I may know in general about traffic rules, I have to be able to respond to a unique car moving where it is not supposed to be, even if my response is only a context-dependent cry, “watch out!” Whether the event at stake is one of unique delicacy like the summer snow flake or mortal danger like the careening auto, I can’t do without attention to the singular event.

So, let me come back to my opening question: how does a cry like “wow!” negotiate the problem of time? Is it only an expedient cry, a singularity that becomes worthless the moment it extends along the arrow of time? Is there any place in art for trying to preserve such vulnerable singular statements? Brecht makes an especially interesting case since he is known for uniting his art with punctual intervention into the politics of his times. But his times aren’t ours. For the politics that his art engaged in to remain relevant, either his interventions would have to have been non-singular—i.e., to have been general, doctrinal—or his singular interventions would have to have been lent enduring expression. I think that we can agree that both are the case, but what strikes me is not the historical ascription of general political meaning to his themes and person—i.e., what is most interesting is not the description of the historical facts of his politics—but how his work still produces singular effects. This question, the one I find interesting, is an old one, and surprisingly hard to get a hold on. In book X of the Republic, Plato imagines asking Homer, “if you are not […] merely that creator of phantoms whom we defined as the imitator, but […] were capable of knowing what pursuits make men better or worse in private or public life, tell us what city was better governed owing to you?”[1] The force of his question is to doubt whether a mimetic art, like poetry or drama, is capable of having the effects that philosophical truth might have on our actions. Art, by contrast, has ahistorical formal merits, or it has fleeting merits, but to the skeptical mind it has no enduring civic value.

Such philosophical curiosity can tempt one “großes Geheimnis zu wittern / Tiefe Metaphysik zu entwickeln,” so let me turn to a brief poem by Brecht, “Die unbesiegliche Inschrift,” to make things more concrete.

Die unbesiegliche Inschrift

2 Zur Zeit des Weltkriegs

3 In einer Zelle des italienischen Gefängnisses San Carlo

4 Voll von verhafteten Soldaten, Betrunkenen und Dieben

5 Kratzte ein sozialistischer Soldat mit Kopierstift in die Wand:

6 Hoch Lenin!

7 Ganz oben, in der halbdunklen Zelle, kaum sichtbar, aber

8 Mit ungeheuren Buchstaben geschrieben.

9 Als die Wärter es sahen, schickten sie einen Maler mit einem Eimer Kalk

10 Und mit einem langstieligen Pinsel übertünchte er die drohende Inschrift.

11 Da er aber mit seinem Kalk nur die Schriftzüge nachfuhr

12 Stand oben in der Zelle nun in Kalk:

13 Hoch Lenin!

14 Erst ein zweiter Maler überstrich das Ganze mit breitem Pinsel

15 So daß es für Stunden weg war, aber gegen Morgen

16 Als der Kalk trocknete, trat darunter die Inschrift wieder hervor:

17 Hoch Lenin!

18 Da schickten die Wärter einen Maurer mit einem Messer gegen die Inschrift vor

19 Und er kratzte Buchstabe für Buchstabe aus, eine Stunde lang

20 Und als er fertig war, stand oben in der Zelle, nun farblos

21 Aber tief in die Mauer geritzt die unbesiegliche Inschrift:

22 Hoch Lenin!

23 Jetzt entfernt die Mauer! sagte der Soldat.

The puzzle of Brecht’s poem lies in what it shares with its unpuzzling hero, the graffiti, “Hoch Lenin!” The phrase in question “Hoch Lenin!” hardly qualifies as a work of art. Like my example of a singular expression, “wow, look at that,” the inscription the poem glorifies seems at first glance to be exhausted by its time-and-place-bound function to exhort. So, the poem’s puzzle might also be put this way: what did Brecht do here to give that undistinguished and obsolete slogan durability and continuing relevance for us? In manuscript draft, Brecht entitled the poem “Propaganda,” and that alternative pair, “Propaganda” and “Invincible Inscription,” only heightens our question about the relationship between momentary urgency and enduring invincibility.

I propose to get at this question by regarding the interpolation of the graffiti into its lyrical context as analogous to the way Brecht sees his actors participating in the epic dramatic context. Essential to Brecht’s conception of epic drama is the disjunction between the time of the play’s setting (with all the urgency of its narrative events) and the time of the play’s performance (with a distinct urgency of contemporaneous events that the production is addressing). The gap, however, allows for something less urgent: a deliberative stance. As Brecht urges “those born later”: “gedenkt unsrer/mit Nachsicht,”[2] where forebearance marks the empirical opposite of an agent-actor’s boldness, which “is ill in counsel, good in execution; so that the right use of bold persons is, that they never command in chief, but be seconds, and under the direction of others” (Francis Bacon).[3] In the Kleines Organon, whose title, as is well known, apostrophizes Bacon’s Novum Organon Scientiarum, Brecht uses the 1947 Charles Laughton version of the Life of Galileo to illustrate his dramatic instrument. It is important that “der zeigende Laughton nicht verschwindet in dem gezeigten Galilei […] dass der wirkliche, der profane Vorgang nicht mehr verschleiert wird” (538). An actor shouldn’t pretend to be immersed in the distant singularity of egos and events, producing the fiction that they are happening again just as they once did, but should open up the distance of time by simultaneously assuming the role of agent and observer of the events. “Steht doch auf der Bühne tatsächlich Laughton und zeigt, wie er sich den Galilei denkt […], das »Jetzt« wie das »Hier« nicht als eine Fiktion […] setzend, sondern es trennend vom Gestern und dem andern Ort” (538-9).

I want to emphasize how this focus on the actor’s schizophrenic displacement of his “jetzt” and his “hier” can be transposed into the lyrical context. In the poem, it is not an actor who splits into the double role of evental agent and critical observer, but the readers of the ringing line, “Hoch Lenin!” The key is to grasp the graffiti as simultaneously a proposition (a bold meaning) and an inscription (a cool token). The meaning, then, can be seen to change with each token of its inscription. But how? How is that difference between a ‘now’ and a ‘yesterday,’ a ‘here’ and an ‘other place,’ brought to bear in a text that isn’t performed? To answer that, we need to posit a reception aesthetics. We can identify a poem whose unity is given by its text, but whose interpretation depends on token acts of reading that fill in what Ingarden called its “Unbestimmtheitstellen.” At these unsaturated spots, the reader is called upon to investigate the relevant predications, or as Brecht says in the Organon, to make “die Verknüpfung der Begebnisse sichtbar” (539). We are the split subjects, receiving the invincible inscription in its objectivity, but instead of submitting to its propaganda, we assume a Baconian spirit and subject its bold meaning to our pragmatic direction. “So gebaut sein muß/Das Werk für die Dauer wie/Die Maschine voll der Mängel.”[4]

If we want to make the flawed inscription “Hoch Lenin” speak to our current affairs, we don’t have complete license. After all, the unity of the poetic text is well stewarded in text-critical editions. So how do we procede? The process is, in fact, the topic of the poem itself. Let’s see how it works by following the graffiti step-by-step, turning to the strange story of its inscription before we turn again to its changing meanings. The soldier first scrawls the lines high up in his dark cell where they can hardly be seen. When the defacement is nonetheless spotted, the guards call a painter to cover it. A process then begins whereby instead of erasing the lines, they are highlighted in a progressively more enduring fashion, from pencil script to painted white wash, to letters carved in the wall. Each repetition is thus an intensification, ending in a quite literal engraving in stone. As Brecht comments elsewhere about monumental writing, “das in den Stein getriebene Wort muß sorgfältig gewählt sein, es wird lange gelesen werden und immer von vielen zugliech” (GBA 22: 141, cited in Thielking, 59).[5] The process by which the offending letters have been reproduced can be seen not only as an intensification, but a depersonalization and dissemination. From the soldier’s colored copy-editor pencil, they now stand there “farblos” but “tief geritzt,” no longer speaking with the subjectivity of his hand, but the objectivity of “das in den Stein getrieben Wort.” Now comes the strangest part. As the pencil-scrawl graduates in the penipenultimate line to “unbesiegliche Inschrift,” the poem’s closing line, a direct quotation of the soldier, demands that the inscribed wall come down. What are we to make of this unexpected end proposed for the inscription?

Although the two words, “hoch Lenin!” seem to do quite well on their own, we need to consider what they might mean. If we were to hear the slogan in some context other than that of the poem, how would we respond? First of all, the slogan follows a formula—a directional adverb plus a noun, like “Vorwärts ___!” “Nieder mit ___!” “Auf, auf___!” or even “Heim ins___!” Because it is an elliptical construction, we can only divine its verbal quality, for example, whether it is an imperative, or, since the missing verb might be “leben” as in “hoch lebe,” a subjunctive. We are told that the date is around the Russian Revolution, so we must read it in context as a wish with an anticipatory aspect, “may the cause of Lenin come to prevail!” At the same time, it is hard to imagine it persuading anyone, as we would assume it was supposed to do if it were meant as a political slogan, since it is barely visible in the cell. Which leads one to think that it is meant more in the way the WWII GI graffiti “Kilroy was here” was intended. As Charles Panati observed about Kilroy, “the outrageousness of the graffiti was not so much what it said, but where it turned up.”[6] It is less to realize a particular aim, than defiantly to assert an objective presence over and against one’s enemies. I remember visiting the old jail in Park City, Utah with chiseled Wobbly slogans still recording defiance after one hundred years. Such graffiti asserts in equal parts the resistant objectivity of the physical mark (which endures even in Kilroy’s past tense, “was here”), and the persistent, anticipatory subjectivity of defiance (“I’m here, unbroken, still hoping for Lenin’s triumph”). Whether one understands it with emphasis on the objective mark or the subjective act, the issue, as we have seen, is settled with its subsequent reinscriptions by the painters and the mason. The physically objective “here”—the San Carlo Prison in Turin—has been emphatically picked out by the increasingly visible inscription. And, with that prominence, what began as only ironically “drohende” pencil scrawling has been transformed into a collective Schlachtruf, an index that serves to orient a battalion of soldiers in the space and time of their charge. In one and the same graffiti, a local “was here” in a San Carlos prison confronts a collective “we” everywhere thronging to the battle cry. That double indexicality sets up the final Witz of the poem.

Brecht’s last line fits more nearly Freud’s Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious than Lenin’s “All Power to the Soviets!” In a joke, accumulated psychic tension is released by exchanging a distressing symbolic meaning for a surface token. So, for example, in the joke, “What comes between fear and sex?—Fünf!” the effect results from the discrepancy between deep symbolic meaning in English and its perfectly banal German phonic equalivents (“vier” and “sechs”), the superficial “fünf” discharging the tension of whatever terrible associations are triggered by fear and sex. Here, the threatening words “hoch Lenin!” can be seen on the surface just to instantiate what they declare: “Lenin” is written “ganz oben,” so, in point of fact, Lenin is “hoch.” The poem’s joke, “now remove the wall!” relieves us suddenly of the ideological burden of that terrible anticipation in the apocalyptic year 1917 when the Russian Revolution might have signaled a new world. The soldier’s quoted “now,” indexes the punchline to the soldier’s diegetic context, rather than our reader-context. Rather than the vague subjunctive call to world revolution, “Hoch Lenin!” we have a precise imperative: not the invincible inscription, which like all stone in Brecht’s oeuvre sucumbs inevitably to time. Rather, what resounds is the punctual command to destroy the inscription along with its imprisoning wall. A gesture of revolt, not revolution.

It is a consummately Brechtian move in two respects. Brecht’s Baconian spirit of induction made him attentive to the singular detail and practical experiment. “Es ist nur nötig,” Brecht writes in the Organon, “—dies aber unbedingt—, daß im großen und ganzen so etwas wie Experimentierbedingungen geschaffen werden, d. h. daß jeweils ein Gegenexperiment denkbar ist.” As Max Weber knew, such a Baconian ideal demands a stiff upper lip in regard to the lifespan of one’s work. “Jeder von uns […] in der Wissenschaft weiß, daß das, was er gearbeitet hat, in 10, 20, 50 Jahren veraltet ist. […] Wissenschaftlich aber überholt zu werden, ist […] nicht nur unser aller Schicksal, sondern unser aller Zweck.”[7] Brecht’s sentiment that “der Wunsch, Werke von langer Dauer zu machen Ist nicht immer zu begrüßen,” was expressed repeatedly in his own work.[8] In “Der Schuh von Empedocles,” his philosopher, rather than being apotheosized in divine nature, as in Hölderlin’s drama, leaves behind his shoe, so that his students, “beschäftigt, großes Geheimnis zu wittern,” suddenly find themselves holding “den Schuh des Lehrers in Händen, den greifbaren/Abgetragenen, den aus Leder, den irdischen.” The thrust of both Weber’s and Brecht’s reflections on the modern condition opposes the prophetic certainty of revelation; what the times demand is essentially tactical, attentive to the inevitable tensions of singular historical experience.

Which takes me to the other respect in which the contradictory wit of the poem’s dialectic of invincibility and immediacy announces its consummately Brechtian attitude. At the end of the Fluchtlingsgespräche, the exiled proletarian Kalle defines socialism in terms that recall the instant after a joke, when all the tension—or contradiction—of revolutionary engagement is fleetingly aufgehoben. Socialism, he says to the cramped intellectual Ziffel, is “wo ein solcher Zustand herrscht, daß solche anstrengenden Tugenden wie Vaterlandsliebe, Freiheitsdurst, Güte, Selbstlosigkeit so wenig nötig sind wie ein Scheißen auf die Heimat, Knechtseligkeit, Roheit und Egoismus.”[9] And that is the key to “Die unbesiegliche Inschrift”: 100 years after “hoch Lenin” was engraved on the wall in San Carlo prison, 100 years after the Russian Revolution, 28 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, we get the joke—it is the List der Vernunft! We saw it before, in 1794, in Büchner’s Dantons Tod, as Desmoulins is guillotined by the Committee of Public Safety, his wife Lucile cries out to the Jacobins: “long live the king!” “Es ist das Gegenwort, es ist das Wort, das dem ‘Draht’ zerreißt,” observes Paul Celan flabbergasted by what the slogan could possibly mean.[10] And there, too, for the length of a “now,” our failed connections are visible—and what’s so funny is “die Gegenwart des Menschlichen zeugenden Majestät des Absurden” (Celan): “als mache sie, was sie macht, als ein Experiment” (Brecht, see above).

Notes:

[1] Plato, 599d, Book 10, Republic. Web. 13 October 2017: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0168%3Abook%3D10%3Asection%3D599d

[2] “An die Nachgeborenen” Gedichte 1, vol. 3, Ausgewählte Werke in sechs Bänden (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1997): 349-351.

[3] See, Francis Bacon, “On Boldness,” The Essays. Web. 13 October 2017: http://www.authorama.com/essays-of-francis-bacon-13.html “This is well to be weighed; that boldness is ever blind; for it seeth not danger, and inconveniences. Therefore it is ill in counsel, good in execution; so that the right use of bold persons is, that they never command in chief, but be seconds, and under the direction of others. For in counsel, it is good to see dangers; and in execution, not to see them, except they be very great.”

[4] Brecht, “Über die Bauart langdauernder Werke,” Gedichte 2, vol. 4, Ausgewählte Werke in sechs Bänden (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1997): 151-153, 152.

[5] Thielking, Sigrid, “L’homme statue”?: Brechts Inschriften im Kontext von Denkmalsdiskurs und Erinnerungspolitik, in Brecht 100 2000, ed. Maarten van Dijk (1999): 53-67.

[6] Wikipedia contributors. “Kilroy was here.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 1 Sep. 2017. Web. 30 Sep. 2017

[7] Max Weber, “Wissenschaft als Beruf.” Web. 13 October 2017: https://de.wikisource.org/wiki/Wissenschaft_als_Beruf

[8] See Jochen Vogt, “Damnatio memorieae und ‘Werke von langer Daer’, Zwei ästhetische Gernzewerte in Brechts Exillyrik,” in Ästhetiken des Exils, ed. Helga Schreckenberger (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2003), 301-318, 305-6.

[9] Brecht, “Flüchtlingsgespräche,” Prosa, vol. 5, Ausgewählte Werke in sechs Bänden (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1997): 9-117, 116.

[10] Paul Celan, “Der Meridian,” Der Meridian und andere Prosa (Frankfurt a. Main: Suhrkamkp, 1983) 40-62, 43.

Bertolt Brecht und die Literaturwissenschaft

by Jost Hermand

[Presented on the panel “The Brechtian Turn” sponsored by the International Brecht Society at the 40th Annual Conference of the German Studies Association in San Diego, California, October 2016.]

Vorwort

I

Angesichts der inzwischen ins Uferlose angeschwollenen Brecht Literatur etwas Sinnvolles zum Thema „Brecht und die Literaturwissenschaft“ zu sagen ist ein geradezu herkulisches Unterfangen. Um mich dabei nicht auf das rein Aufzählende zu beschränken, was die Kenner notwendig langweilen und die mit diesen Schriften weniger Vertrauten eher abschrecken würde, verfahre ich deshalb im Folgenden – im Hinblick auf die verschiedenen Phasen dieser Forschungsrichtung – lieber argumentativ, indem ich sie vorwiegend auf ihren ideologischen Stellenwert befrage. Ja, nicht nur das: um dem Ganzen einen gesellschaftspolitischen Fokus zu geben, fasse ich dabei – wohl oder übel – lediglich die innerdeutsche Entwicklung dieser Forschungsrichtung ins Auge und gehe auf die außerdeutsche Brecht-Literatur nur dann ein, wo sie auf die Brecht-Forschung oder den Streit um Brecht in der DDR, der ehemaligen BRD und der heutigen sogenannten Berliner Republik eingewirkt hat. Und selbst dabei übergehe ich die geradezu unübersehbare Fülle an journalistischen Beiträgen und Theaterkritiken und erwähne nur das, worin die wichtigsten Literatur- und Theaterwissenschaftler dieser drei Staaten die Bedeutsamkeit von Brecht gesehen haben. Doch im Rahmen eines abrissartigen Vorworts wird selbst das etwas kursorisch ausfallen.

II

Eine spezifisch literaturwissenschaftliche Auseinandersetzung mit Brechts Oeuvre und seinen darin vertretenen gesellschaftspolitischen Anschauungen begann – nach 15 Jahren einer relativen Nichtbeachtung im skandinavischen und US-amerikanischen Exil – erst, als Brecht in der Anfangsphase des Kalten Krieges 1948 im sowjetzonalen Ostberlin Fuß zu fassen versuchte. Wie sehr man dort diese Entscheidung begrüßte, beweist schon ein im Jahr 1949 von Peter Huchel herausgegebenes Sonderheft von Sinn und Form, das ausschließlich seinem Werk gewidmet war. Allerdings verhinderte die zum gleichen Zeitpunkt in der SBZ einsetzende Formalismus-Debatte (in der, wie wir wissen, einige einflussreiche SED-Kulturfunktionäre Brecht Verstöße gegen die alleingültige Doktrin der Sozialistischen Realismus vorwarfen) erst einmal ein genaueres Eingehen auf die Grundprinzipien seiner literarischen Schreibweise.

Erst nach dem zwischen 1952 und 1954 einsetzenden Ruhm seines Berliner Ensembles setzte daher in der inzwischen gegründeten DDR eine parteipolitische und literaturwissenschaftliche Würdigung seiner Werke ein. Dafür sprechen nicht nur die Gedenkreden, die Walter Ulbricht, Johannes R. Becher, Paul Wandel und Georg Lukács nach seinem Tod im August 1956 unter dem Motto „Du verließest uns viel zu früh“ an seinem Grabe oder im Berliner Ensemble hielten, sondern auch die ersten über ihn erscheinenden literaturwissenschaftlichen Studien, allen voran Ernst Schumacher mit seinem Buch Die dramatischen Versuche Bertolt Brechts 1918-1933 (1955), mit dem er kurz zuvor bei Hans Mayer in Leipzig promoviert hatte. Darauf erschienen in der DDR in schneller Folge weitere Brecht-Studien von Hans Joachim Bunge, Käthe Rülicke-Weiler, Gerhard Zwerenz, sowie das 2. Brecht-Sonderheft von Sinn und Form, in denen es vor allem darum ging, die Entwicklung Brechts von seiner anarchistischen Jugendphase zu seinen späteren marxistisch orientierten Positionen herauszustellen. Damit waren die wichtigsten Voraussetzungen geschaffen, auf denen sich in den frühen sechziger Jahren eine breitgefächerte Brecht-Forschung in der DDR entfalten konnte, zu deren Hauptvertretern zwischen 1960 und 1965 vor allem Werner Hecht, Hans Kaufmann, Klaus Schuhmann und besonders Werner Mittenzwei gehörten, die sich inzwischen weitgehend aus den Fesseln der Formalismus-Debatte gelöst hatten und neben Brechts marxistischer Grundhaltung auch die Bedeutung seiner Verfremdungstechnik sowie seiner Materialwerttheorie akzentuierten, statt ihm weiterhin auf erpenbeckmesser’sche Weise den Vorwurf zu machen, sich nicht an die maßstabsetzenden Lehren Konstantin Stanislawskis gehalten zu haben.

III

Wie zu erwarten, vollzog sich in der BRD die politische und literaturwissenschaftliche Auseinandersetzung mit Brecht während der fünfziger und frühen sechziger Jahre unter völlig anderen ideologischen Vorbedingungen. Hier schwieg man sich, ob nun auf konservativer oder neoliberaler Ebene – aufgrund der herrschenden antikommunistischen Propagandawellen – über ihn, wie auch über andere links orientierte Exilautoren, entweder aus, oder man trat jenen Theaterregisseuren, die es dennoch wagten, einige seiner Stücke zu inszenieren, vor allem in den spannungsreichen Jahren 1953 (17. Juni), 1956 (Ungarnaufstand) und 1961 (Mauerbau), mit massiven Boykottdrohungen entgegen. Und auch die mit der Adenauersehen Restaurationspolitik konformgehende bundesrepublikanische Germanistik, die sich fast ausschließlich mit goethezeitlichen oder romantischen Dichtungen beziehungsweise der biedermeierlichen Literatur der Metternichschen Restaurationsperiode beschäftigte, ging – wegen der faschistischen Vergangenheit vieler ihrer maßgeblichen Vertreter – aus begreiflicher Berührungsangst aller als „politisch“ geltender Literatur von vornherein aus dem Wege. Dafür nur ein Beispiel. Als ich 1957, nach einem längeren Aufenthalt in Ostberlin, vor Marburger Studenten einen Vortrag über „Brecht und das Berliner Ensemble“ hielt, sagte einer der führenden westdeutschen Neugermanisten dieser Jahre, bei dem ich 1955 – auf sein Drängen hin – mit einer Dissertation über „Die literarische Formenwelt des Biedermeier“ promoviert hatte, anschließend ironisch lächelnd zu mir: „Ja, aber wer ist denn dieser Herr Brecht?“

Was damals in der westdeutschen Germanistik – unter völliger Nichtbeachtung irgendwelcher gesellschaftskritischen Aspekte – als positiv galt, waren lediglich die sogenannten literarischen Bauformen, aber nicht der ideologische Aussagewert von Dichtungen. Wer sich deshalb in diesem Staat überhaupt literaturwissenschaftlich mit Brecht beschäftigte, stellte daher, wie Franz Herbert Crumbach, Otto Mann oder Jürgen Rühle, Brechts Weltanschauung von vornherein als „verfehlt“ hin oder bezichtigte ihn im Jargon des Kalten Kriegs, lediglich ein literarischer Handlanger jenes „Schinderregimes“ jenseits des Eisernen Vorhangs gewesen zu sein, in dem man jede freiheitlichindividuelle Regung rücksichtslos unterdrückt habe.

Die ersten, welche dieser Haltung in der frühen BRD auf germanistischer Seite widersprachen, waren zwischen 1957 und 1959 Reinhold Grimm, Walter Hinck, Marianne Kesting, Volker Klotz und Klaus Völker, die sich in Anlehnung an Peter Szondis Theorien über offene und geschlossene Bauformen des Dramas, wenn auch unter Weglassung aller von Brecht geforderten Grundprinzipien des dialektischen Materialismus marxistischer Prägung, vornehmlich mit der Herausstellung bestimmter dramaturgischer Techniken, durch Komik erzielter Verfremdungseffekte sowie ähnlich gearteter Themenstellungen beschäftigten, sich also bei ihren Rechtfertigungsstrategien vor allem auf formale Kriterien stützten. Falls dabei überhaupt ideologische Aspekte ins Spiel kamen, wichen sie wie Marianne Kesting zumeist ins Journalistisch-Unverbindliche aus, indem sie Brecht als eine „geheimnisvolle Widerstandsfigur“ charakterisierten, der es vornehmlich um die Durchsetzung seiner Form des Theaters, aber nicht um irgendwelche gesellschaftskritische oder gar weltverändernde Absichten gegangen sei.

IV