Table of Contents

125 JAHRE BRECHT / BRECHT AT 125:

Brechts Gespenst: Zur Veröffentlichung der gesammelten Interviews von Bertolt Brecht an seinem 125. Geburtstag (Noah Willumsen)

„Ändere die Welt, sie braucht es“ Brecht heute in Berlin– nach 125 Jahren (Florian Vaßen)

Introduction to The Threepenny Opera (Steve Giles)

GSA PANEL 2022:

- A Lehrstück on the Stage of the Berliner Ensemble? Alexander Eisenach’s Die Vielleichtsager (2022-2023) (Francesco Sani)

- Ernst Bloch’s The Principle of Hope, Anna Seghers, and Sigmar Polke (Caroline Rupprecht)

- Twin Branches of the Epic Tree: Bertolt Brecht, Erwin Piscator and Interventionist Aesthetics in the Post-War Germanies (Mark W. Clark)

MLA PANEL 2023:

- Herr Keuner and the Foundations of Incorruptible Democracy (Luke Beller)

- Brecht and Democracy (Marc Silberman)

PERFORMANCE REVIEW:

Bertolt Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle at St. Norbert College (Ellen C. Kirkendall)

INTERVIEWS

Interviews with Carl Weber: Working with Brecht (Branislav Jakovljević)

Brechts Gespenst: Zur Veröffentlichung der gesammelten Interviews von Bertolt Brecht an seinem 125. Geburtstag

Noah Willumsen

Am 9. Februar 2023 wurde Brechts 125. Geburtstag in der Akademie der Künste feierlich begangen. Nach einer Begrüßung von Akademie-Vizepräsidentin Kathrin Röggla und der Festrede von Kulturministerin Claudia Roth wurden von Dr. Fabian Leber, dem Sprecher des Finanzministers Christian Lindner, ein neues Postwertzeichen und eine 20-Euro-Sammler-Münze präsentiert. Briefmarke und Geldstück ziert nicht nur Brechts Porträt, sondern auch ein denkwürdiges Brecht-Wort: „Ändere die Welt, sie braucht es.“

In der hier nachgedruckten Rede, die Noah Willumsen im Anschluss hielt, stellt er den von ihm herausgegebenen Band Bertolt Brecht: „Unsere Hoffnung heute ist die Krise.“ Interviews 1926–1956, vor und reflektiert über die politischen und medialen Bedingungen, unter denen wir Brecht 2023 gedenken. Auszüge aus den Interviews wurden danach von zwei Schauspielern des Berliner Ensembles, Maximilian Diehle und Paul Herwig, vorgelesen.

Am 16. Mai 1955 sah sich die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung zu folgender Richtigstellung gezwungen:

Die Aeußerungen des Intendanten Heinz Hilpert […] in Göttingen sind durch Hör- und Druckfehler leider entstellt wiedergegeben worden. So hat Hilpert Bert Brecht nicht als „Toren,“ sondern als „Autoren“ bezeichnet.“[1]

Auch für Schriftsteller:innen ist der Umgang mit den Medien schwer. Gezwungen, wie Brecht schreibt, „durch immer dichtere Medien zu sprechen,“ ist die Gefahr von Missverständnissen groß, Wohlwollen nicht immer vorauszusetzen. „Merkwürdig,“ konstatiert Brecht, selbst Leser der FAZ, „was man da so alles über sich erfährt.“[2] Auf diese neuen Arbeitsmittel einfach zu verzichten, hieße jedoch an der Welt, die von ihnen konstruiert wird, nicht mehr teilzunehmen.[3]

Brechts Versuche, durch Massenmedien öffentlich zu intervenieren – seine Interviews – sind aber nach seinem Tod 1956 aus dem Gedächtnis der Literatur verschwunden. Lange galt, dass der medienscheue Brecht diese Art von Publicity strikt gemieden hätte.[4] Journalist:innen habe er, in den Worten eines Freundes, „oft gründlich verulkt,“ und schon zu seinen Lebzeiten berichteten Gutgläubige, er würde alle, die ihn interviewen wollen, mit dem Ruf „Ich hasse Sie!“ hinausschmeißen.[5] Im Laufe der letzten fünf Jahre habe ich trotzdem nach solchen Gesprächen gesucht, sie gesammelt, ediert und übersetzen lassen, und kann Ihnen heute 91 Interviews mit Brecht präsentieren, fast alle bisher unbekannt und unvermutet, die in 15 Ländern und in 11 Sprachen erschienen. Bevor wir von Maximilian Diehle und Paul Herwig ein paar Auszüge hören, möchte ich erzählen, wie diese Texte nun nach 67 bzw. 97 Jahren wieder ans Licht gekommen sind, was wir Neues darin finden können, und warum Brechts Medienarbeit gerade jetzt für uns so wesentlich ist.

Manche dieser Interviews lagen in den tieferen Schichten des Brecht-Archivs, wo der durchaus imagebewusste Dichter und seine Mitarbeiter:innen sie sammelten, die meisten waren dennoch recht verstreut, in finnischen Bibliotheken, sowjetischen Datenbanken, oder brasilianischen Theaterfakultäten. Wenn in einer Ost-Berliner Gewerkschaftszeitung erwähnt wird, dass Brecht mit einer tschechischen Zeitschrift gesprochen hat, hat man oft wenig mehr als einen terminus ante quem. Aber wenn man Glück hat, merkt man beim verständnislosen Durchblättern hunderter zerfallender Zeitungsseiten die kleine Brecht-Skizze oben links.[6] Manche Wege sind recht verschlungen. In den 1980er Jahren z. B. hat Heiner Müller – der unzuverlässigste Erzähler, den man sich nur wünschen kann – behauptet, das erste, was er von Brecht gehört habe, sei ein Interview im Nordwestdeutschen Rundfunk gewesen, kurz nach Kriegsende: „Das Weitermachen schafft die Zerstörung, die Kontinuität schafft die Zerstörung.“[7] Ein schöner Satz! Aber lohnt es sich, solchen dubiosen Anekdoten nachzujagen? In der Tat. Denn dieser Spruch verharrte tatsächlich siebzig Jahre lang nicht nur im Gedächtnis Heiner Müllers, sondern fast wortgleich auf den Tonbändern des NWDR, die glücklicherweise vor ihrer Vernichtung digitalisiert wurden.[8]

Neue Technologien der Speicherung und Erschließung machen Projekte wie dieses in einem bisher ungeahnten Ausmaß möglich – und in den kommenden Jahren werden wir unsere Bilder von vielen Schriftsteller:innen sicherlich noch revidieren müssen. Wir stehen 2023 auf der Schwelle zwischen einer immer umfassenderen Digitalisierung, die auf die richtigen Fragen ganz neue Antworten zu geben verspricht, und dem reißenden Zahn der Zeit, dem Papier, Magnetband und Menschengedächtnis unausweichlich zum Opfer fallen. Drei von Brechts Gesprächspartner:innen sind seit Anfang dieses Projektes gestorben; keine konnte ich noch erreichen. Aber ein Satz wie der, den Heiner Müller mit 20 Jahren im Rundfunk hörte, der die Tragödien und Hoffnungen des vergangenen Jahrhunderts kristallisiert: Der ist haltbar. Und er kann noch heute wirken.

Brechts Interviews werden, glaube ich, auch jenseits seiner angestammten Leserschaft vielen etwas zu bieten haben. Es gibt natürlich weitere solcher schlagenden Formulierungen, wie man sie von Brecht erwartet: Der Unterschied zwischen Schriftstellern und Dieben etwa sei nur, dass Diebe zumeist wissen, wo sie ihr Zeug herhaben, oder: Wo man mit der Ästhetik, als Lehre vom Schönen, nicht weiterkomme, müsse man’s mit der Lehre vom Unschönen versuchen, nämlich der Soziologie.[9] Hier wird zum ersten Mal das epische Theater erwähnt, sowie das Theater des wissenschaftlichen Zeitalters: Überhaupt hat Brecht seine Theorien am liebsten im Gespräch getestet und geschliffen.[10] Wir finden unter seinen Interviewer:innen auch ganz neue dramatis personae: Figuren, die man mit Brecht nie in Verbindung gebracht hat, wesentliche Persönlichkeiten der Weimarer Literaturszene, die, von Hitler ermordet oder vertrieben, in Vergessenheit geraten sind, aber auch Menschen, die nie wieder auffällig wurden und nur im Bernstein dieser einzigartigen Begegnung aufgehoben sind, und deren Geschichten hier zum ersten Mal erzählt werden konnten. Der wichtigste Fund ist jedoch die Form selbst: Hier ist eine völlig neue Seite von Brechts Schaffen zu entdecken, eine, die heute unsere Aufmerksamkeit in besonderer Weise beansprucht: Seine Beschäftigung nicht nur mit Kunstmedien – wie dem Film oder dem Grammophon –, sondern mit Nachrichtenmedien, vor allem Zeitungen und Zeitschriften.

In einer komplexen Gesellschaft, wie sie im Berlin der 20er Jahre dieses und des letzten Jahrhunderts zu finden ist und war, sind alle zwangsläufig auf andere angewiesen, die ihnen die Welt außerhalb ihres begrenzten Erfahrungskreises zur Verfügung stellen.[11] Die Wahrheit ist in diesem Sinne immer ein soziales Produkt, für dessen Herstellung, wie Brecht schreibt, einige „öffentliche[] Institutionen“ zuständig sind, die Informationen validieren: die Universität, die er oft zu erwähnen vergaß, das „Gericht,“ das zum Modell seines Theaters wurde – aber vor allem die „Presse,“ die zu Brechts Lebzeiten einen kaum vorstellbaren Bedeutungszuwachs erfuhr.[12] Schon 1926 konnte er feststellen, „dass selbst Gott sich über die Welt nur mehr aus den Zeitungen orientiert.“[13] Allein in Berlin gab es 2633 davon (inkl. Zeitschriften), als Die Dreigroschenoper auf die Bühne kam.[14]

Diese massive Industrialisierung von Information wirkte aber genauso wenig aufklärerisch, wie ihre Digitalisierung einige Jahrzehnte später; der Ausgang des Menschen aus seiner bisherigen Unwissenheit scheint ihn in seine Unmündigkeit nur tiefer hineingeführt zu haben.[15] Die „ungeheure Entwicklung“ der Medien, so Brecht, sei „für die Wahrheit über die Zustände, die auf der Welt herrschen, kaum ein Gewinn gewesen.“[16] Stattdessen, wie Brecht schnell erkannte, wurde durch die plötzliche Verfügbarkeit von Welt die Struktur unserer Wahrnehmung grundsätzlich verändert. Wie er sagt: „wir machen unsere Erfahrungen [nun] in katastrophaler Form,“ als „Objekte und nicht Subjekte“ der Ereignisse, die uns schon längst widerfahren sind, als wir sie zu begreifen versuchen. Diese Verspätung zur eigenen Geschichte wird durch die zunehmende Geschwindigkeit der Nachrichten nicht verringert, sie ist vielmehr ein konstitutiver Aspekt unseres Medienkonsums: „Wir fühlen schon beim Lesen der Zeitungen,“ so Brecht, „daß irgendwer irgendwas gemacht haben muß, damit diese offenbare Katastrophe eintrat.“ Unserer „Schlußfolgerungen“ müssen wir „im nachhinein, von der Katastrophe aus“ vornehmen; und so kommt es, dass „hinter den Ereignissen, die uns gemeldet werden, wir andere Geschehnisse vermuten, die uns nicht gemeldet werden.“[17] Der Nachrichtenkonsument – der Doomscroller, wenn man so will – ist also strukturell zum Paranoiker bestimmt. Die tautologische Vergewisserung, facts are facts, ist für ihn kein Trost, sondern bezeichnet, allerdings mit einiger Genauigkeit, seine Unfreiheit: Heißt das lateinische factum das Gemachte, so werden Fakten geschaffen – aber nicht von ihm.

Der Zustand der Institutionen, in deren Händen die „Produktionsmittel“ der Wahrheit konzentriert sind, ist heute wie in Brechts Tagen desolat.[18] Kein Zufall, dass Journalist:innen und Wissenschaftler:innen wieder zu den bevorzugten Angriffszielen rechter Gewalt in Deutschland zählen, dass Universitäten und Gerichte die Brennpunkte kultureller und politischer Auseinandersetzungen in den USA bilden. Dass die Zirkulation unserer immer umkämpfteren sozialen Wahrheit gewinnorientierten Plattformen obliegt, die darin in erster Linie einen Köder für unsere Aufmerksamkeit sehen, die wiederum an Werbekunden verkauft werden kann, hätte Brecht auch kaum überrascht.[19] So dystopisch ihr Geschäftsmodell erscheinen mag, haben es Facebook, Twitter und YouTube mit nur wenigen Änderungen vom allerersten Massenmedium übernehmen können, dem durchaus treffend benannten General-Anzeiger, das heißt: der Tageszeitung.[20] Hier wurde ein eigentümliches Regime der Wahrheit begründet, in dem die Zuverlässigkeit von Informationen durch Professionelle verbürgt wird, die Bereitstellung von Information jedoch durch scheinbar unbeteiligte Geschäftsleute finanziert – vor allem durch Werbung.[21] „Wahrheit“ war, so Brecht, zur „Ware“ geworden.[22] Keiner unabhängigen Plattform, ob gedruckt oder elektronisch, und vertritt sie auch die radikalste Presse- und Meinungsfreiheit, ist es seitdem gelungen, diese strukturelle Verknüpfung von Kapital und Wahrheit zu überwinden.[23]

Stattdessen hat die Digitalisierung (wie schon die Industrialisierung) dazu geführt, dass die mittelständischen Qualitätsproduzenten auf dem Informationsmarkt von konkurrenzfähigeren, rentableren Billigwarenhändlern verdrängt werden. Im Unterschied zum heutigen Kommentariat empfand Brecht für die Untergehenden allerdings weder Mitleid noch Nostalgie. Die Zeitung sei „in den Händen der Bourgeoisie zu einer furchtbaren Waffe gegen die Wahrheit geworden,“ „das riesige [M]aterial, das tagtäglich von den Druckerpressen ausgespien wird und den Charakter der Wahrheit zu haben scheint, dien[e] in Wirklichkeit nur der Verdunkelung der Tatbestände.“[24]

Brecht war jedoch kein Querdenker. In einer aufschlussreichen Keuner-Geschichte behauptet ein gewisser Herr Wirr – eine uns allen inzwischen gutbekannte Figur –, er sei „ein großer Gegner der Zeitungen,“ er wolle „keine Zeitungen.“ Worauf der schlagfertige Herr Keuner entgegnet: „Ich bin ein größerer Gegner der Zeitungen: ich will andere Zeitungen.“[25] Brecht lehnte es ab, bloß ‚Content‘ herzustellen, um die Medien, wie er schreibt, „auf der Basis der gegebenen Gesellschaftsordnung zu erneuern“; aber er trat ihnen ohne Umschweife entgegen, um sie „durch Neuerungen zur Aufgabe ihrer Basis zu bewegen.“[26]

Dabei weigerte er sich radikal zu dozieren, zu indoktrinieren oder talking points wiederzukäuen. Er verzettelte sich keineswegs in Abstraktionen, sondern versuchte, wie sich der Philosoph Georg Lukács erinnerte, mit der „Wucht“ seiner Sprache in seinem Publikum „heilsame Krisen“ zu provozieren.[27] „[D]ie einzig ertragreiche Methode“ sei, nach Brecht, „kaltblütig einige einfache Töpfe“ anzuschaffen und alles hineinzuwerfen.[28] Freunde berichten von den „sehr zugespitzte[n] Meinungen“ und „scharfe[n], angreifende[n] Sentenzen,“ die er hervorbrachte, „um die Menschen zu reizen, um sie herauszulocken, um die Situation dramatischer zu gestalten.“[29] So kategorisch er seine Aphorismen geltend zu machen pflegte, wollte Brecht die alten Fragen nicht ein für alle Mal beantworten, sondern gewohnte Frageweisen stören, „Vorgängen den Stempel des Vertrauten wegnehmen“ und damit „[d]ie großen öffentlichen Denkprozesse“ anstacheln.[30]

Interviews dienten Brecht nicht dazu, den ‚wahren Sinn‘ seiner Texte zu offenbaren. Danach gefragt, antwortete er konsequent: „Es ist besser, das bleiben zu lassen. Ich bräuchte kein Theaterstück zu schreiben, wenn ich hier sitzen und Ihnen die Bedeutung in wenigen Worten sagen könnte.“[31] Würde er das tun, müsste er auch seine Interviews zu bloßen Kommentaren entwerten, die – ohne eigene Substanz – andere Werke auslegen, erklären oder wiederholen würden: eine Angelegenheit für Abiturienten. Vielleicht als erster jedoch sah Brecht im Interview eine eigenständige Form, mit neuen Möglichkeiten, Leser- und Zuhörer:innen zu erreichen und herauszufordern, zu überraschen und zu verführen.

Auch im Politischen, so pointiert er seine Analysen zu formulieren verstand, trat er nicht mit der letztgültigen Wahrheit auf. Autoren, sagt er, seien „keine Missionare,“ er wolle weder „Orakel“ noch „Leithammel,“ „weder Spiegel noch Sprachrohr“ für irgendeine Partei sein.[32] Vielmehr erkämpfte er innerhalb der Medien, einen Raum für die Literatur als autonomes Zentrum der Wahrheitsproduktion, das sich neben Politik, Justiz oder Wissenschaft behaupten könnte:

Aus Sicht der Gesellschaft [so Brecht] ist ein Schriftsteller, der keine persönlichen Ansichten hat, wertlos. Um nützlich zu sein, muss er Neues beitragen. Ein Theatermann muss nicht beim Staat in die Lehre gehen. Der Staat hingegen kann vom Dramatiker lernen; es gibt tatsächlich immer Probleme, mit denen eine Gesellschaft nicht fertig wird: Auf diesem Gebiet arbeitet der Schriftsteller; seine Imagination kann hilfreich sein, um diese Aufgaben zu erfüllen; er kann sogar neue aufdecken.[33]

Ein Interview ist eine Flaschenpost auf dem Meer der Massenmedien, als ephemere Form von einer Dialektik von Geschichtlichkeit und Vergänglichkeit gezeichnet. Morgen taucht es vielleicht unter, in hundert Jahren kann es allerdings wieder angespült werden und uns so direkt ansprechen, als hätte es allein auf diesen einzigen Adressaten gewartet. Man hört darin eine Stimme wieder, die nicht mehr spricht, aber kein Begräbnis zum Schweigen bringen konnte. Eine Stimme, die aufgenommen werden will, von Stiften und Tonbändern, aber auch, verehrtes Publikum, von Ihnen. Wir Gedenkenden, die verspäteten Leser:innen von Brechts Interviews, haben es also mit „der Zu-kunft und der Wiederkunft eines Gespenstes“ zu tun, das in Europa offenbar noch zirkuliert.[34] In Interviews werden, um ein altes Wort zu gebrauchen, Gespenster zitiert. Um den Teufel auszutreiben, werde bekanntlich Beelzebub zitiert: Wen treiben wir aus, wenn wir Brecht zitieren?

Das Brecht-Zitat, unter dem wir heute Abend versammelt sind, lautet nicht, wie der Spruch von Hamlets Vater auf den Mauern von Helsingör: „Gedenke mein,“ geschweige denn: „räch [m]einen schnöden, unerhörten Mord!“[35] „Ändere die Welt“ bleibt dennoch ein schauriger Auftrag[36], der uns aus der Vergangenheit erreicht, um uns an uneingelöste Hoffnungen, begangenes Unrecht und drohende Gefahr zu erinnern, eine geschichtliche Hypothek, die mit ganz anderer Münze abbezahlt werden will. Die Worte sind Brechts tour de force, Die Maßnahme, entnommen:

Welche Niedrigkeit begingest du nicht, um Die Niedrigkeit auszutilgen? Könntest du die Welt endlich verändern, wofür Wärest du dir zu gut? Versinke in Schmutz Umarme den Schlächter, aber Ändere die Welt: sie braucht es![37]

Sicherlich gehört es zu den Ironien der deutschen Brecht-Rezeption, dass dieser Schrei nach einem gewalttätigen Umsturz des Kapitalismus uns heute auf einem Geldstück begegnet. Aber damit ist auch genau die Stelle markiert, an der Brecht glaubte, dass wir die Welt ändern müssen, wenn sie bewohnbar bleiben – oder dies erst werden soll.

Ich bedanke mich.

[1] Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 17. Mai 1955, S. 5.

[2] Zit. nach Erwin Strittmatter, „Besuch bei Brecht heute,“ in Wochenpost, 13. April 1957, S. 40.

[3] Vgl. Warum haben Sie keinen Fernseher, Herr Luhmann? Letzte Gespräche mit Niklas Luhmann, hg. v. Wolfgang Hagen (Berlin: Kadmos, 2005), S. 85, sowie Der Dreigroschenprozess, BFA 21, S. 446.

[4] Vgl. Chetana Nagavajara, Brecht and France (Bern: Peter Lang, 1994), S. 50.

[5] Hanns Otto Münsterer, Bert Brecht. Erinnerungen aus den Jahren 1917–1922 (Berlin/Weimar: Aufbau, 1966), S. 5; Bertolt Brecht, „Unsere Hoffnung heute ist die Krise“: Interviews 1926–1956, hg. v. Noah Willumsen (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2023), S. 562.

[6] Vgl. Brecht 2023, S. 354–59.

[7] Heiner Müller, Gespräche 1. 1965–1987, Werke 10 (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2008), S. 288; vgl. S. 692. Erdmut Wizisla hat Müller 1994 über die Quelle von diesem Spruch befragt, vgl. Heiner Müller, Gespräche 3. 1991–1995, Werke 12 (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2008), S. 503f.

[8] Vgl. Brecht 2023, S. 367–71; dort heißt es: „Die Kontinuität, sagt er paradox, macht die Zerstörung. […] Das Weitermachen, das macht die Zerstörung.“

[9] Vgl. Brecht 2023, S. 639, 84.

[10] Brecht 2023, S. 32, bzw. 46; S. 89f.

[11] Vgl. Steven Shapin, A Social History of Truth (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1994), S. XXVf.

[12] Der Dreigroschenprozess, BFA 21, S. 448. Luhmann würde hier nicht von ‚Wahrheit‘ sondern von ‚Wissen‘ als einem „sozial validierte[n] Verhältnis von Organismus bzw. psychischem System und Umwelt“ sprechen: Das Erziehungssystem der Gesellschaft (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2002), S. 98.

[13] „Über die Zeitungen an Karl Kraus,“ BFA 21, S 153.

[14]Alfred Joachim Fischer, In der Nähe der Ereignisse. Als jüdischer Journalist in diesem Jahrhundert (Berlin: Transit, 1991), S. 27; Fischer interviewte Brecht 1930, vgl. Brecht 2023, S. 113–19.

[15] Vgl. Marcel Broersma and Chris Peters, „Rethinking journalism: the structural transformation of a public good,“ Rethinking Journalism. Trust and Participation in a Transformed News Landscape, hg. v. dens. (New York: Routledge, 2012), S. 1–12.

[16] „[Zum zehnjährigen Bestehen der ‚A-I-Z‘],“ BFA 21, S. 515.

[17] „Über die Popularität des Kriminalromans,“ BFA 22.1, S. 509f.

[18] „[Nutzen der Wahrheit],“ BFA 21, S. 580.

[19] Zu den Dynamiken von „advertising platforms,“ siehe Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2017), insb. S. 50–60. Werbeeinnahmen beliefen sich auf 97,5% der Gesamteinnahmen von Meta im letzten Kalenderjahr (https://s21.q4cdn.com/399680738/files/doc_financials/2022/q4/Earnings-Presentation-Q4-2022.pdf); im gleichen Zeitraum machte Werbung 90% der Einnahmen von Twitter aus (https://www.businessofapps.com/data/twitter-statistics/).

[20] Zeitungen sind „canonical two-sided market[s]“ (Marc Rysman, „The Economics of Two-Sided Markets,“ Journal of Economic Perspectives 23:3 [2009], S. 125–143: 128). Wie Online-Plattformen konkurrieren sie um „advertisers as well as ‚eyeballs.‘“ Obwohl sie seltener zum Nullpreis angeboten werden, ist der Zeitungsmarkt ebenfalls von asymmetrischen Preisstrukturen, d. h. von einer weitgehenden Subventionierung der einen Seite (Leserschaft/User) durch die andere (Werbekunden), charakterisiert (Jean-Charles Rochet und Jean Tirole: „Two-Sided Markets. A Progress Report,“ RAND Journal of Economics 37:3 [2006], S. 645–67: 645, 659).

[21] Vgl. Marco D’Eramo, „Rise and Fall of the Daily Paper,“ New Left Review 111 (2018), S. 113–27.

[22] „[Nutzen der Wahrheit],“ BFA 21, S. 580.

[23] Srnicek identifiziert drei Gegenmodelle: „cooperative platforms,“ die sich durch gnadenlose Selbstausbeutung (und Spenden) über Wasser halten; staatliche Regulierung bis zur Verstaatlichung, deren Ergebnisse Brecht in der Weimarer Republik, bzw. DDR, kennen und wenig schätzen lernen konnte; und schließlich Vergesellschaftung, infolgedessen man „public platforms […] owned and controlled by the people“ als Träger der öffentlichen (Informations-)Versorgung operieren würde (Srnicek 2017, S. 127f.). Letztere kommt Brechts Vorschlag, aus dem Rundfunk z. B. „eine wirklich demokratische Sache zu machen,“ am nächsten („Vorschläge für den Intendanten des Rundfunks,“ BFA 21, S. 215).

[24] „[Zum zehnjährigen Bestehen der ‚A-I-Z‘],“ BFA 21, S. 515.

[25] „[Herr Keuner begegnete Herrn Wirr],“ BFA 18, S. 30.

[26] „Der Rundfunk als Kommunikationsapparat,“ BFA 21, S. 557.

[27] Georg Lukács, „Mitten im Aufstieg verließ er uns. Gedenkansprache auf der Trauerfeier im Haus des Berliner Ensembles,“ Neues Deutschland, 21. August 1956, S. 4.

[28] „Captatiae. Traktat über ein episches Theater,“ BFA 21, S. 682f.

[29] Fritz Sternberg, Der Dichter und die Ratio. Erinnerungen an Bertolt Brecht (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2014), S. 36.

[30] Kleines Organon für das Theater, BFA 23, S. 81; „Kommune Notate,“ BBA 1081/044.

[31] Brecht 2023, S. 175.

[32] Brecht 2023, S. 583, 397, 584.

[33] Brecht 2023, S. 584.

[34] Jacques Derrida, Marx’ Gespenster. Der Staat der Schuld, die Trauerarbeit und die neue Internationale (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 1995), S. 67.

[35] William Shakespeare, Hamlet. Prinz vom Dänemark, über. August Wilhelm Schlegel, I.v.

[36] „Bei aller polaren Gegensätzlichkeit zu Rilke“, so Georg Lukács, „ist also dessen: ‚Du mußt dein Leben ändern‘ auch das Axiom für das künstlerische Wollen Brechts,“ Eigenart des Ästhetischen I. Werke, Bd. 11, hg. von F. Benseler (Neuwied am Rhein: Luchterhand, 1963), S. 825.

[37] Die Maßnahme (1930), BFA 3, S. 89.

„Ändere die Welt, sie braucht es“ Brecht heute in Berlin– nach 125 Jahren

Florian Vaßen

Vor 125 wurde Bertolt Brecht in Augsburg geboren, Grund genug ihn deutschlandweit in vielfältigen Formen zu feiern und zu ehren, vor allem auch in Berlin, Brechts Wohnsitz in der Weimarer Republik und nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg und zugleich Ort seines weltberühmten Erfolgs mit der Dreigroschenoper und später mit dem Berliner Ensemble.

Die Akademie der Künste: Unsere Hoffnung heute ist die Krise

Die Akademie der Künste feierte Bertolt Brecht mit einer Buchpräsentation und der Vorstellung einer 85-Cent-Briefmarke und einer 20-Euro-Münze. Nach der Begrüßung durch Kathrin Röggla, der Vizepräsidentin der Akademie, und einem Grußwort von Claudia Roth, Staatsministerin für Kultur und Medien, übergab das von der FDP geführte, nicht unbedingt Brecht-nahe Wirtschaftsministerium eine eckige Briefmarke und eine runde Münze zu diesem nicht ganz so runden Geburtstag.

In der DDR gab es schon viele Brecht-Briefmarken, die erste 1957, in der BRD dagegen keine einzige, 1998 dann eine erste gesamtdeutsche. Auf der neuen Briefmarke ist neben dem Namen, den Jahreszahlen und einem Foto von Brecht aus dem Jahr 1954 – ein ästhetisch störender QR Code war wohl auch notwendig – ein Sprachrohr zu sehen, aus dem der Satz „Ändere die Welt: Sie braucht es!“ agitatorisch herausschallt. So isoliert stehend, können vermutlich sehr viele Menschen ganz unterschiedlicher politischer Ausrichtung diesem Satz zustimmen, in dem Kontext, in dem Brecht ihn in Die Maßnahme (BFA 3, 116) gebraucht, bekommt er dagegen eine erhebliche politische Brisanz, die sicherlich nicht im Sinne der FDP ist. Die Münze zeigt stattdessen einen nachdenklichen Brecht mit gerunzelter Stirn, den Daumen am Kinn und eine Zigarre in der Hand, und der Satz „Ändere die Welt: Sie braucht es!“ steht unter dem Porträt.

Im Folgenden präsentierte Noah Willumsen mit einer differenzierten Einführung die von ihm herausgegebene Publikation Unsere Hoffnung heute ist die Krise. Interviews 1926–1956 (Berlin: Suhrkamp 2023), in der 91 in deutscher Sprache unveröffentlichte Interviews mit Brecht versammelt sind, die sicherlich neue Akzente in unserem Brecht-Bild setzen werden. Nach der Einspielung von zwei originalen Tondokumenten von Brecht trugen zwei Schauspieler Auszüge aus einigen Interviews vor.

Das Berliner Ensemble: Ändere die Welt, sie braucht es

Das Berliner Ensemble veranstaltete vom 10. bis 12. Februar zu Brechts 125. Geburtstag ein Brecht-Wochenende mit drei Brecht-Inszenierungen aus dem Repertoire (Christina Tscharyiskis Brechts Die Mutter. Anleitung für eine Revolution aus einer feministischen Perspektive mit einer Live-Band, Oliver Kraushaars Solo Der Lebenslauf des Boxers Samson-Körner in der Regie von Dennis Krauß und Suse Wächters Puppenspiel Brechts Gespenster) sowie mit dem inszenierten Audioworkshop Brecht to go, in dem die Teilnehmer*innen, ausgehend von Brechts berühmter Straßenszene, sich aktiv mit seinem Theaterverständnis auseinandersetzen konnten. Unter dem Titel Ändere die Welt, sie braucht es fand am 12. Februar zudem ein Thementag mit drei Podiumsdiskussionen zu Bertolt Brechts Aktualität statt, auf denen, ausgehend vom Denken Brechts, Expert*innen aus verschiedenen Bereichen, u.a. die Sozialwissenschaftlerin Bafta Sarbo, der Soziologe Klaus Dörre und die Regisseurin Christina Tscharyiski, über die Widersprüche unserer Zeit diskutierten. Dabei ging es vor allem um „die Frage der Legitimität von institutioneller und individueller Gewalt, um die Möglichkeit von sozialer Gerechtigkeit und Gemeinwohl vor dem Hintergrund einer sich immer weiter ausdifferenzierenden Gesellschaft und schließlich um die Rolle der Kunst in der Gesellschaft.“ (https://www.berliner-ensemble) Schauspieler*innen des Berliner Ensembles lasen dazu jeweils passende Passagen aus Brechts Werken.

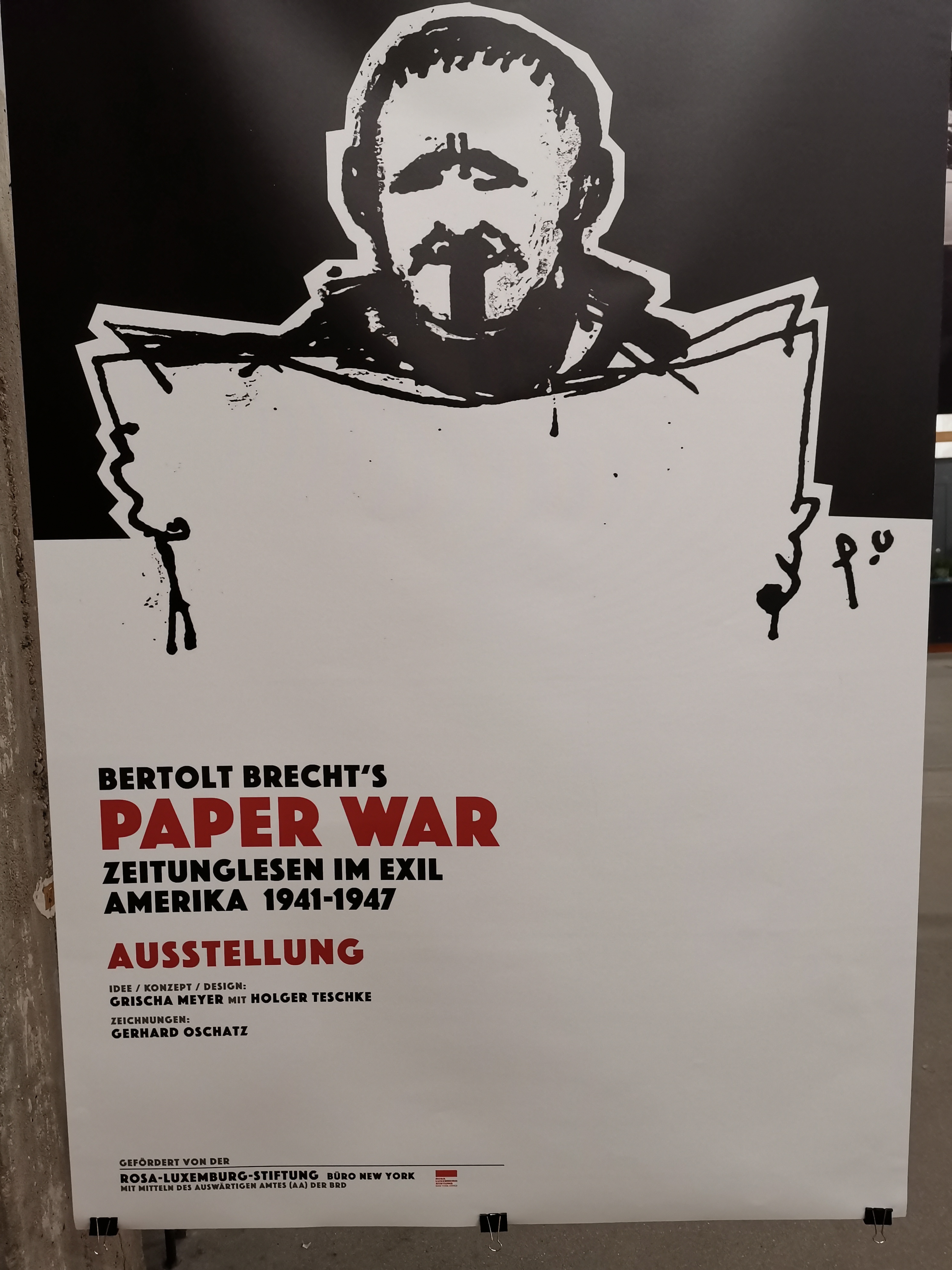

Bertolt Brechts Papierkrieg

Aus gegebenem Anlass präsentierten Grischa Meyer und Holger Teschke im Foyer der Hochschule für Schauspielkunst Ernst Buch vom 20. Januar bis zum 3. März die Ausstellung Bertolt Brechts Papierkrieg. Zeitungslesen im Exil Amerika 1941–1947 (zuvor im Goethe Institut in New York unter dem Titel Bertolt Brecht’s Paper War. Zeitungslesen im Exil Amerika 1941–1947), in der Brechts Arbeitsweise an der Kriegsfibel, inklusive zusätzliches, bisher nicht bekanntes Material, gezeigt wird.

Bertolt Brechts Kriegsfibel. Ihr aber lernet, wie man sieht statt stiert

Die wichtigste Veranstaltung zu Brechts Geburtstag waren aber auch in diesem Jahr die Brecht-Tage vom 6.–10. Februar im Literaturforum im Brecht-Haus. Unter dem Titel Brechts „Kriegsfibel“. Ihr aber lernet, wie man sieht statt stiert fanden an fünf Tagen Vorträge, Diskussionen und performative Präsentationen über das spezifische Verhältnis von Bild und Text statt, ergänzt um den Bereich der Musik, und mit einer besonderen Akzentuierung auf die Gegenwart, den Krieg heute und die Fortsetzung bzw. Weiterentwicklung der Brecht’schen Methode.

So präsentierten gleich am ersten Tag Armin Smailovic und Dirk Gieselmann ihren Atlas der Angst, mit Bildern und Texten von einer Fahrt durch Deutschland, in denen nicht nur die Stimmung in der Bevölkerung dokumentiert wurde, sondern auch die unterschiedlichen Dimensionen und Bedeutungen von Krieg thematisiert wurden. Es folgten am zweiten Tag Zeichnungen von Johannes Weilandt, der mit seiner Bleistift-Stricheltechnik Luftaufnahmen von sog. smart bombs u.a. im Irakkrieg verfremdete. Beides scheinen mir interessante Arbeiten, die für mich jedoch nicht die Intensität der Brecht’schen Kriegsfibel erreichen. Volker Brauns Lesung mit dem Titel KriegsErklärung, die vermutlich besonders produktiv gewesen wäre, musste wegen eines Unfalls des Autors leider verschoben werden.

In dem ersten Vortrag der Brecht-Tage analysierte Ulrike Haß in einer Art Stratigraphie unter dem Titel Erdbebenzone Eurasien die Schichten, Verwerfungen und Risse der europäischen Ost-West-Verhältnisse. Ausgangspunkte sind, laut Haß, vor allem die Zerstörung Trojas durch die Griechen, die spätere reduzierte Kopie Griechenlands durch Rom, die Trennung in eine ost- und eine weströmische Kirche und der Gegensatz von Nomaden und Sesshaften, Konstellationen, die sie auch an Euripides‘ Troerinnen und Heiner Müllers Philoktet konkretisierte.

Der dritte Tag der Brecht-Tage stand im Zeichen der Musik: Während Johannes Gall sehr präzise Hanns Eislers Vertonung Bilder aus der ’Kriegsfibel‘ analysierte und an eingespielten Beispielen Eislers Nähe zu Brecht erläuterte, bildeten die neu übersetzten poetischen Verse vom unbekannten Soldaten von Ossip Mandelstam einen intensiven und eindringlichen Kontrast zu Brechts Antikriegstexten. Die Vertonung von Mandelstams Lyrik und deren musikalische Präsentation in russischer Sprache durch das Ensemble lesabendio haben mich dagegen nicht angesprochen, sie blieben mir sehr fremd, ja sie verstärkten meines Erachtens das Klischee von der „russischen Seele“.

Alexander Kluge: Montieren gegen den Krieg

Im Zentrum der Brecht-Tage stand zweifelsohne der Donnerstagabend mit Alexander Kluge, der unter dem Titel Montieren gegen den Krieg mit short cuts aus seinen Filmen und im Gespräch per Zoom mit Erik Zielke sowohl die Wechselseitigkeit von Wort und Bild in einer Art ‚Bild-Rede‘ darlegte als auch eine vielfältige Analyse des Krieges gab. Kluge betonte mit der Stafette der Jahre 1898, 1914, 1918 und 1929 die Entwicklung des jungen Brecht. Wichtig sei vor allem das Jahr 1929, u.a. mit dem sogenannten Blutmai, dem ersten Treffen von Brecht und Benjamin und mit Aby Warburgs Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, einer der letzten Zeitpunkte, um den Nationalsozialismus möglicherweise noch zu verhindern. Bereits 1934 „röhrt und tobt der Faschismus in ganz Europa“, wie Kluge formulierte, während Brecht und Benjamin sich in Dänemark als zwei „Robinsone“ schon über den drohenden Krieg, das Zurückgehen zum Anfang, zum Einfachen, aber auch zum Verlorenen, über Mut und „messianische Kraft“ neben der realen politischen Kraft durchaus auch kontrovers unterhalten. Die Brecht-Benjamin-Beziehung versinnbildlicht Kluge in den beiden sehr unterschiedlichen Figurationen Engel der Geschichte und Stachel der Clown von Paul Klee, letztere vor allem nach Art von Rabelais und Bachtin als Ausdruck des Lachens und des Zwerchfells gegen das „Versteinerte in uns“. Neben dieser geschichtsphilosophisch-ästhetischen Personen-Konstellation betont Kluge mit Brecht und Eisenstein, die sich auch 1929 in Berlin trafen (und Dziga Wertow als dessen dokumentarischem Kontrast), zweitens den montagehaften filmischen Aspekt, insbesondere Eisensteins „kugelförmige Dramaturgie“ der nicht linearen „Triptychon-Montage“. Schließlich spricht Kluge die soziologisch-politische Verbindung von Brecht und Karl Korsch an, dem Brecht die ersten Tafeln der Kriegsfibel geschickt hat. Insbesondere betont Kluge Korschs Überlegungen zum „Blitzkrieg“ als „Flucht nach vorn“ sowie zum Rückzug als „wandernder Kessel“ und „Blitzkrieg nach rückwärts“ der Proletarier in Uniform, wie es Rosa Luxemburg nennt. Kluge thematisiert weiterhin die Illusion der Sicherheit durch Panzerung, Panzer seien eher „glühende Särge“ (Heiner Müller), und ist besorgt, dass der Ukrainekrieg heute wie der Erste Weltkrieg 1914 „ansteckend“ sein könne. Es sei ein weiter und gefährlicher Weg von Gorbatschow bis Putin. Mit Brechts „Fatzer“, der bekanntlich ja desertiert, betont Kluge, dass viel Mut notwendig ist, um einen Krieg zu beenden, und dass Erfahrungen wichtiger seien als überschwängliche Moral.

Kluge geht es vor allem um „Weltzusammenhang“ und „Welterfahrung“, um Koinzidenzen, wie er sie am Beispiel des 30. April 1945 aufzeigt, ein Montag, an dem Hitler Selbstmord begeht, in San Francisco die Vereinten Nationen gegründet werden und sich in Oakland Arbeiterorganisationen aus aller Welt treffen; Brecht arbeitet zur gleichen Zeit an der Hexameter-Versifizierung des Kommunistischen Manifests.

Abschließend fragt sich Kluge, wie Krieg darstellbar ist und gibt selbst filmische Beispiele: Das Schmelzen von Bleisoldaten im knisternden Feuer war z.B. ein außergewöhnlich intensives Bild von Tod und Zerstörung im Krieg, oder die irritierende Montage von „staunenden“ Tierfiguren aus dem Bilderbuch für Kinder, einem mehrbändigen Sach- und Lehrbuch von Friedrich Justin Bertuch (1747–1822), Benjamins Lieblingslektüre, mit Bildern des menschlichen Krieges. Auch Kluge präsentierte keine „Lösung“, zumal das einfache Abbilden nur die „Lebenswelt“, nicht aber die „Systemwelt“ zeige. Deshalb müsse etwas Neues konstellativ hergestellt werden durch Mehrperspektivität von Wort, Bild, Foto, Film etc. Es gehe um die Kooperation der Archive (etwa von Brecht, Walter Benjamin und Heinrich Heine) und um dialektische Bilder. Brecht und Benjamin sind nach Kluge nicht tot, sie erwarten sozusagen, dass wir ihre Arbeit fortführen.

Den Krieg madig machen

Es ist schon Tradition bei den Brecht-Tagen, dass im Gegensatz zu den vorhergehenden Abendveranstaltungen während des gesamten Freitags mehrere Kurzvorträge aufeinander folgen. Die Thematik Den Krieg madig machen, wie das Motto lautete, war jedoch bedauerlicherweise keineswegs in allen Vorträgen der Bezugspunkt. Während Christoph Hesse sich auf die Aspekte Montage und Demontage, Film- und Bild-Montage konzentrierte, thematisierte Sabine Kebir Brechts Auseinandersetzung mit dem globalen Krieg – in der Kriegsfibel sind auch viele Bezüge zum asiatischen Raum – sowie die grundlegenden und höchst problematischen Veränderungen, die seit dem Vietnamkrieg über die Kriege im Nahen Osten bis zu den heutigen Stellvertreterkriegen in Bezug auf das Bildmaterial und dessen Veröffentlichung in den Medien festzustellen sind.

Nach einer kleinen Feier am Grab auf dem Dorotheenstädtischen Friedhof und im Hof des Brecht-Hauses, kurzen, klugen und unterhaltsamen Reden und der Musik der „Bolschewistischen Kurkapelle Schwarz-Rot“ sprach Gerd Koch am Nachmittag in seinem „Feature“ von einem „Dreier-Verbund“ von Brecht und den beiden Bildenden Künstlern Hans Tombrock und Pieter Breughel dem Älteren. Dabei ging es – ganz im Sinne des Mottos des Tages – um Mutter Courages Ausspruch „Der Krieg soll verflucht sein“, ein „kleiner Satz“, der allerdings in ein notwendiges „Beiwerk“ eingebettet werden muss, wie Brecht es mit Blick auf Breughel formuliert. Analog zur Kriegsfibel spricht Brecht mit Tombrock im schwedischen Exil von „Tafelwerken“ als „freie Assoziation“ von Bild und Gedicht. Die Verbindung des „geschriebenen“ und des „gemalten Gedankens“ als zwei „Standpunkte“, präsentiert im öffentlichen Raum, würden – laut Brecht und Tombrock – die Diskussion intensivieren und damit auch den Kunstgenuss. Den Abschluss bildeten zwei Vorträge von Anna Melnikova und von Luise Meier, deren Bezug zum Thema Den Krieg madig machen ich nicht erkennen konnte. Die Körper-Reflexionen bzw. die Lehrstück-bezogene Selbstreflexivität und Selbstadressierung bildeten einen eigenartigen, aber vielleicht auch verständlichen ratlosen Abschluss.

Brechts Friedensfibel gegen „finstere Zeiten“?

Mein Eindruck der diesjährigen Brecht-Tage ist zwar insgesamt positiv, aber doch auch zwiespältig: Bei den ästhetischen ‚Zugriffen‘ fehlte mir vor allem die ästhetisch-politische Intensität und Radikalität, die in der Kriegsfibel immer noch zu finden ist und die ebenfalls bei Alexander Kluge vorhanden ist[1]. Auch die theoretischen Überlegungen einerseits zum Krieg und dessen Begrifflichkeit sowie andererseits zur Wort-Bild-Kombination und zur Montage hätten wohl grundsätzlicher ausfallen können; auch hier ist Kluge wieder die große Ausnahme. Meine Hauptkritik gilt aber der Tatsache, dass sich die Vorträge und Präsentationen doch sehr unterschiedlich auf das zentrale Thema bezogen und ein Weiterdenken und -arbeiten auch im Sinne von Brechts Projekt einer Friedensfibel kaum sichtbar war. Heterogenität ist gut, aber das gemeinsame Thema sollte doch im Zentrum der Reflexionen und künstlerischen Arbeiten stehen. Wir leben in „finsteren Zeiten“, wie Brecht formuliert, gerade deshalb sollten aber unser Blick durchdringend, unser Denken entschieden und unsere Haltung widerständig sein.

[1] Alexander Kluges gesamter Zoom-Auftritt lässt sich in der Mediathek des Literaturforums im Brecht-Haus nachverfolgen; siehe https://lfbrecht.de/mediathek/brecht-tage-2023-montieren-gegen-den-krieg/

Introduction to The Threepenny Opera

Steve Giles

The years from 1926 to 1932 constitute one of the most productive and problematic phases in Brecht’s career. He wrote several major plays and numerous theoretical essays, and made significant progress in developing the practice of epic theatre. He was also involved in collaborative ventures with several avant-garde composers, among them Hindemith, Eisler, and of course Weill. The Threepenny Opera, the first major product of his work with Weill, was written and premiered in 1928. It occupies a central position in this phase in Brecht’s career, a phase of particular importance in Brecht’s shift to Marxism. Accordingly, The Threepenny Opera has tended to be seen as a transitional work, not only in terms of Brecht’s politics, but also as regards his developing theory and practice of epic theatre. It is also a transitional work in the more fundamental sense that it was itself a work in transition, which Brecht rewrote in 1931, and it is this later version of the text that forms the basis for the ‘standard’ edition reprinted in the standard, English-language Methuen edition. In this discussion I shall concentrate on the three aspects just outlined (a) the problematic status of the text, (b) the theatrical significance of The Threepenny Opera, (c) the politics of The Threepenny Opera. I don’t intend to comment in any detail on the work’s musicological significance, as this is beyond my area of competence: may I simply recommend Stephen Hinton’s excellent Cambridge Opera Handbook.

TEXT:

(a) The 1928 version: this version of the text is a collaborative reworking and adaptation of Elisabeth Hauptmann’s translation of John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera. Indeed, so many hands were involved in the final stages of the production of the text and theatrical premiere that this version of the text certainly cannot be construed as a play ‘by Brecht’. In 1931, however, Brecht revised the 1928 version of the text in quite crucial ways; I shall first briefly outline the main directions which these changes move in, and then give some key examples.

(b) The 1931 version has generally been seen as an attempt to give a Marxist gloss to a work whose original politics where rather more vague. While there is some truth in this view, the changes made in 1931 are more complex and modify the text in four main ways:

1. Peachum and Macheath are endowed with a higher level ideological self-awareness, rendering more explicit the text’s critique of capitalist society.

2. The development of Macheath’s calculating and entrepreneurial tendencies is paralleled in Polly’s enhanced independence, self-control and economic pragmatism.

3. Sexuality is presented as a potentially autonomous motivating force.

4. The relationship between self, role and discourse becomes much more complex. I shall comment on 3 and 4 when I discuss the text’s theatrical and political dimensions later on: what I shall do now is look briefly at the changes to Macheath and Polly (though as we shall see, these changes also have implications for 3 and 4). The revisions to Macheath’s part mainly concern his status as criminal or bourgeois and his social image, and the most striking 1931 addition to the text underlines his bourgeois attributes, indicated in particular through his new career as a banker [see Macheath’s final speech, scene 9, p.76]. As far as Polly is concerned, in 1931 she is presented as far more autonomous and self confident in her dealings with Macheath, who had been much more dominating and domineering in the 1928 version. Polly’s increased autonomy and self-control is also bound up with the new emphasis on her economic rationality, indicated in her business-like exchanges with Macheath in scene 9 [pp.72-3]. At the same time, the fact that she breaks down at the end of this encounter illustrates a further key element in the 1931 conception of her role, namely the conflict between her affective and rational tendencies. As well as being more internally conflictual, though, her role also becomes more complex – her capacity for playacting and deception, and her highly self-conscious control of discursive levels in her encounters with Lucy, are particularly important here [scene 8].

THEATRE:

The comments I’ve just made on role play, on discursive levels, on role conflict, bring us to the theatrical dimension of The Threepenny Opera. It clearly isn’t possible for me to give a detailed account of the theory and practice of epic theatre at this point, and so what I shall do is 1) give an impression of the direction in which Brecht’s views on theatre were moving 1928–31, 2) comment on aspects of the ‘standard’ 1931 version of The Threepenny Opera in terms of epic theatre.

As far as Brecht’s views on theatre are concerned, there are four main tendencies in his thinking from the mid 1920s onwards, and the general trend between 1928 and 1931 is that his views become more explicitly Marxist.

1. Brecht constantly attacks the dominant institution of the theatre, which he wishes to see replaced by a more experimental and politicized form of theatre that pays detailed attention to the economic structures of capitalist society and to class struggle.

2. He advocates a radical shift in the role and response of the audience, which must become more critical and questioning.

3. He is acutely aware of the need for a new type of writing for the theatre, which must deal with the complexities of capitalist society.

4. He tends increasingly to use a Marxist base/superstructure model in his accounts of cultural and social phenomena.

I shall deal with politics of theatre in the final section of this discussion and concentrate now on the means by which Brecht wishes to provoke the audience into a more critical and questioning response, in particular through his use of self-conscious theatricality.

Brecht was particularly concerned that the audience should not be deluded into thinking that what they saw on stage was a slice of real life, and so one of his techniques is to expose and undermine traditional dramatic devices. In structural terms, The Threepenny Opera is a classic piece of epic composition. It constantly undermines the evolutionary dynamic of dramatic writing in that there is no causal or organic link between one scene and the next, and linear flow within scenes is disrupted because they are organized in terms of montage. Moreover, the spectator’s awareness of the text’s epic structure is reinforced by its estrangement of traditional dramatic devices.

The Threepenny Opera consists of three acts, each of which has three scenes and culminates in a ‘Threepenny Finale’, but this symmetry is broken by the addition of a Prologue and an Interlude played in front of the curtain. Similarly, the text self-consciously plays with the temporal conventions associated with the neo-classical unities [note the references to clock time in scene 9]. These self-reflexive tendencies also underlie Peachum’s concession to the audience that the ending has been changed so that, in the opera at least, we will see justice tempered by mercy. The Threepenny Opera’s most provocative example of estrangement is, however, Polly’s thematisation of epic theatre as a demonstration or replay when she introduces the ‘Pirate Jenny’ song [scene 2, pp.19-20]. Her interpolation of epic theatre within epic theatre is particularly important in drawing the spectator’s attention to the link between the text’s estrangement of dramatic discourse and its presentation of role play.

The opening scene of The Threepenny Opera, with its sardonic presentation of the rhetoric of woe, is built around the notion that acting involves a distanced display of behavioural attitudes, so that we are invited from the beginning to consider the relationship between figures in the work and their roles. Are they no more than the passive products of the roles they play, do they suffer from role conflict, do they actively play their roles with distance? In Polly’s case, these questions are particularly difficult to resolve, presumably in order to frustrate any attempts at identification on the part of the spectator. While, on some occasions, she appears to be a rather adolescent and incorrigible romantic, on others she comes across as a hard-boiled business woman, lurching from role to role and even breaking down if the conflict between them becomes too acute. At the same time, we are made aware from the ‘Pirate Jenny’ song onwards of an element of duplicity and deceit in her behavior that compels us to ask ourselves constantly whether or not she is playing a particular role with distance.

Role distance is also crucial in the presentation of Macheath. He appears to be able to compartmentalize his roles when they threaten to come into conflict, and this leads to the abrupt discontinuities in his behavior instanced in his shifting attitudes first towards Polly and then towards his men in scene 4. Nevertheless, even Macheath is not entirely in control of his behaviour, and this is because he is a character in transition. Although he aspires to exchange the status of criminal for that of banker, his incomplete adoption of bourgeois role attributes is signalled by the discrepancies in and between his verbal and physical behavior in the wedding scene, ironically counterpointed by Mathias’s repetitions of his high-falutin diction [scene 2, p.17].

The Threepenny Opera’s highlighting of the link between role and discourse, graphically exemplified in Polly’s ability to find the mot juste when she takes on the leadership of the gang [scene 4, p.38], is fundamental to its unmasking of ideology. The text is characterized by frequent collisions of discursive level, notably in the course of Polly’s and Jenny’s altercation after the ‘Jealousy Duet’. Although in this latter case the text focuses on the figures’ skill in manipulating discourse, it also exposes the inseparability of language and ideology and their saturation of interpersonal behavior. This applies particularly to its demystification of the rhetoric of romantic love, which is inaugurated by Mrs. Peachum’s attack on the ‘Can’t-you-feel-my-heartbeat’ text (subsequently taken up in the love duet at the end of scene 2), and reaches a harrowing climax in Brown’s fond farewell to Macheath in scene 9. Indeed, The Threepenny Opera’s estrangement of discourse informs not just its presentation of love, but its investigation of all ‘natural’ human sentiments from friendship to filiality. The tone is set in the opening scene, where Peachum laments the threadbare nature of texts which are intended to provoke pity and generosity, but which have become debilitated through over-use. The juxtaposition of the registers of sentiment and economics, both here and in Polly’s comparison of the moon of love to a worn-down penny at the end of scene 4, also invites us to consider the materialist dimension to The Threepenny Opera’s account of social relations, so I shall now to go on to consider the work’s politics.

POLITICS:

Even since its premiere in 1928, The Threepenny Opera’s Marxist credentials have been a matter of controversy. The Threepenny Opera was subjected to a devastating attack in the communist daily The Red Flag, according to which it contained not a trace of political satire and reflected its authors’ inability to depict the revolutionary working class. As we’ve already seen, the 1931 version can be construed as an attempt to make amends in this respect, but it does so in a rather ambivalent manner. I shall try to bring out this ambivalence by looking at the work’s account of economic and sexual relationships, and I’ll finish by considering the work’s ‘revolutionary’ potential.

The exploitative nature of the capitalist economy is grotesquely demonstrated through the nature of Peachum’s business, as his employees exchange a proportion of their labour power for begging licenses. Although Peachum’s firm is a pre-industrial enterprise and the text does not address itself specifically to commodity production, it does emphasize the commercialization of all interpersonal relationships under capitalism, especially bourgeois marriage and prostitution. At the same time, it is precisely in the sphere of sexual relationships that the apparent primacy of economics is obscured. The ‘Ballad of Sexual Slavery’ [added in 1931] implies that Macheath’s behaviour is determined by his sexual appetites, and despite Brecht’s claim to the contrary (‘Texts by Brecht’, Methuen edition, pp. 92-3), Macheath’s virtual satyriasis is amply confirmed by the variety and frequency of his sexual encounters. Just as Peachum’s relationship to his employees denotes the economic organization of capitalism, so Macheath’s relationships to women and his implicitly homoerotic friendship with Brown indicate its sexual organization. The Threepenny Opera demonstrates that in bourgeois society, all forms of sexuality are defined in relation to the norm of masculinity. Thus, the sexual identity of women in particular, whether as wives, lovers or prostitutes, is presented as deriving from dependency on men, even though the precise nature of this dependency is mediated in socio-economic terms.

The text’s detailed attention to human sexuality is complemented by its recognition of other biologically based material needs, most starkly in the ‘Second Finale’: ‘Food is the first thing. Morals follow on’ (scene 6, pp. 55-6) At first sight, these words appear to lend credence to the view that Brecht’s position in The Threepenny Opera is ultimately no different from Freud’s in Civilisation and its Discontents, emphasising the primacy of biological needs and human viciousness, and implying that the conditions condemned in the ‘First Finale’ are natural and unchangeable rather than historical and political. However, this would be to overlook the fact that the immediate context of ‘Food is the first thing’ refers to the differential socio-economic distribution of the means to satisfy basic human requirements. There is a strong case for arguing that the text’s overall presentation of social relationships is consistent with Brecht’s thesis that the physicality of human beings must be construed in terms of socio-economic processes in which it is set. While this involves a crucial modification of Brecht’s more orthodox Marxist contention that the human essence is no more than an ensemble of societal relationships, it also means that The Threepenny Opera’s approach to material needs involves a descriptive and explanatory model, which avoids the pitfalls of both economic and biological reductionism.

The absurd deus ex machina which rounds off The Threepenny Opera, and underlines the absence of mercy and justice for all in the non-operatic world of capitalism, is put into perspective by Peachum’s reminder that the King’s messengers appear only infrequently and that the down-trodden will kick back. The Threepenny Opera’s materialist account of the ideological and social relations of capitalism thus seems to be complemented by a confident assurance of revolutionary praxis; nevertheless, the models of resistance encountered in the work are problematic. Typically, whether in Macheath’s ‘Forgiveness’ ballad in scene 9, the ‘Pirate Jenny’ song in scene 2, or the First Finale, ‘kicking back’ simply involves recourse to physical violence generated by resentment or frustration of material needs: it may well be that this is why Brecht stated in 1945 that, in the absence of a revolutionary movement, the work’s message was pure anarchism. There is certainly no attempt to present a revolutionary movement within The Threepenny Opera, but the work’s failure to engage with the problem of generating collective political action ultimately derives from its analysis of capitalism. While The Threepenny Opera provides a compelling account of ideology and commodification, from a Marxist point of view it is far less adequate in its consideration of social class. While the lower orders of capitalist society are presented exclusively as members of the Lumpenproletartiat, state power is embodied in the pathetic figure of Brown. Consequently, there is no real sense of class conflict in the work, nor of its grounding in the conflict between forces and relations of production. Although the final stanza of the ‘Third Finale’ ironically invites us to embark on a deconstruction of legal and religious superstructures, it seems to be oblivious of the fact that for Marx, the distorted conceptions of ideology can only be overcome practically, by changing the contradictory societal relations that generate ideology. The Threepenny Opera presents a fascinating interpretation of the world: but from a Marxist point of view, the point is to change it.

References and further reading

Brecht, Bertolt, The Threepenny Opera (London, Methuen, 1979) Collected Plays, Volume 2 Part 2, translated by Ralph Manheim and John Willett.

Giles, Steve, ‘From Althusser to Brecht: Formalism, Materialism and the Threepenny Opera’, in Richard Sheppard (ed) New Ways in Germanistik (Berg, 1990), 261-77.

Giles, Steve, ‘Rewriting Brecht: Die Dreigroschenoper 1928–1931’, Literaturwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch, 30 (1989), 249-79.

Hinton, Stephen, Kurt Weill – The Threepenny Opera (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

A Lehrstück on the Stage of the Berliner Ensemble? Alexander Eisenach’s Die Vielleichtsager (2022–2023)

Francesco Sani

Two things occupy my mind as I sit down in the auditorium of the Berliner Ensemble’s Neues Haus to watch Die Vielleichtsager, written and directed by Alexander Eisenach.[1] The first is the stage where a square platform is placed. A structure of poles sustains some curtains that depict two panels of a triptych by Edo Japan Woodblock-print artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi. I have seen this print before, but I need to resort to Google to remember the title. The triptych is titled “Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre” and shows a scene from legend where a sorceress summons a demon in the form of a giant skeleton to kill a warrior named Mitsukuni.[2] The panel where the sorceress is depicted does not appear, and the scene now seems to show a man hunted by an animated skeleton: what in the Western artistic tradition would correspond to a memento mori. The other thing is the conversation between playwright and director Alexander Eisenach and theatre scholar Patrick Primavesi that I have just read in the evening’s programme. Primavesi’s first lengthy contribution to the conversation provides some context on the Lehrstück, what Brecht meant by the term, and in what historical conditions he operated. Primavesi seems to focus quite a lot on the fact that Brecht worked on the Learning Plays as an experimentation and, as he states, without a solid aesthetic and political theorisation behind his work: “Ende der 1920er Jahre hat er an diversen Projekten gleichzeitig gearbeitet, dafür aber noch keine systematische Theorie und auch noch keine gefestigte politische Haltung. So wurde er in der Weimarer Republik mit seinen Stücken und Aufführungsversuchen auch von kommunistischer Kritik missverstanden.”[3] Primavesi also clarifies that the Lehrstück is about conducting an intellectual process through performance: “Es ging nicht um fertige Produkte, sondern um Prozesse, um experimentelle Versuche.”[4] Eisenach’s interventions reveal his interest in Brecht’s secularisation of ritual and his belief that the “Lehrstücke für uns heute vielleicht einen Wert haben, weil wir in einer stark ideologisierten, aber gleichzeitig entideologisierten Zeit leben.”[5]

I have expectations now: the performance programme promises a work in dialogue with Brecht’s original experiments and with the intention of tackling the subtle nature of ideological consensus in neoliberalism (Primavesi uses the term in the programme).[6] The scenography seems to hint at a central element of Brecht and Weill’s the Jasager, which is a rewriting of the Nō play Taniko: the use of elements drawn from Japanese culture but decontextualised and reinvented in a different (Western) aesthetic paradigm. As the platform starts rotating, it is possible to see that the pole structure divides it in four spaces, one of which is reserved for musicians Sven Michelson and Niklas Kraft, who perform on stage throughout the show. Malick Bauer starts singing the prologue of Brecht’s Jasager/Neinsager. The music is not Kurt Weill’s: Bauer sings while employing a voice synthesiser on a simple arrangement performed on percussions and guitar that feels like a pop song. The estranging experience of hearing Brecht’s speculative but straightforward lines on a catchy, modern musical base is followed by a change of scene that strongly echoes the Jasager: a scholar, performed by Peter Moltzen, is to go to the mountains to conduct research in hydrothermal energy to save Germany from an energy crisis during the cold winter of 2022. He informs his two students, Malick Bauer and Lili Epply, of the necessity to undertake this dangerous journey and eventually accepts to bring them along, insofar as they understand the responsibilities and risks that come with the endeavour. All three of them wear long white tunics, which resemble those in which ancient Chinese philosophers are traditionally depicted. The acting is a mixture of naturalistic mimesis interspersed with comical gags and stylised elements that seem to bear a ritualistic meaning, like the steady walk the two pupils perform at the start of the conversation with their teacher. Successively, one of the students, Lili Epply, starts narrating the beginning of the expedition and the passage from civilisation into the wilderness. This is followed by another dramatic scene in which one of the pupils, Malick Bauer, who sang the prologue, feels sick, and the teacher and the other student decide to leave him behind and kill him, this time with his consent. The scholar states that he brought a gun, and many in the audience around me laugh when he states so in a tone that hints at the fact that he is surprised at finding the weapon in his sleeve. Before shooting the student, he tears off one of the curtains. Once again, this appears as an almost ritualistic action, which however is not given a context of reference or purpose.

This took around half-an-hour, probably less. Now Lili Epply sings the Jasager’s prologue again. This time it sounds like a different genre of popular music: a melodical ballad in a style that, at first impression, makes me think of pop singer Adele. This time the role of the master/scholar is taken by Malick Bauer, who is to leave earth in the year 2122 on a mission to colonise Mars. Epply and Moltzen are not his students but his colleagues, whom he decides to bring along after they insist both on account of their scientific interest and the promise of a better life. Moltzen narrates the beginning of the expedition as Epply did before. Subsequently Epply asks to go back when she sees the earth from above: she is the one who cannot respect the duty undertaken by consenting to be part of the expedition. After a debate on the legitimacy of abandoning planet earth in a state of environmental destruction instead of trying to save it, Bauer and Moltzen reluctantly decide to kill Epply. A revolver appears in Bauer’s sleeve, and the two tear down the rest of the curtains wearing them like belts (another ritualised but uncontextualized action). However, Epply refuses to consent to her own killing and convinces them to go back to earth (she is, so to speak, a Neinsager who enables change in the collective). In the third and conclusive part of the performance, Moltzen sings the Jasager’s prologue as a punk rock tune. Epply is the scholar guiding the expedition, which in this case is a submarine journey to make contact with some intellectually advanced octopi that will prove to be a vital partner for humanity in the year 2222. Bauer narrates the first part of the journey. And Moltzen is the one to be killed because the molluscs species ask for a human sacrifice. Also, his colleagues find out that he purchases squid meat on the black market and accuse him of discriminating against the undersea species. He, however, answers with a “Vielleicht” when asked to give consent to his execution. The three performers take off their vests and remain in black tights. Now they question the very premises of the choice offered: the fact that maybe the human sacrifice was not requested but was a miscommunication with the octopi; that maybe it is not right to kill someone even when they are despicable individuals; or that maybe individual sacrifice is not always good for the collective or necessary.

When the lights are turned on in the auditorium and the audience starts applauding, I am aware that there is a message to process from the play. The message is a rather clearly outlined one and one I was made aware of when I first saw the production advertised on the Berliner Ensemble’s website: “Ist ein “Vielleicht” wirklich haltungslos? Oder kann es, anstatt an einem blinden Fortschrittsglauben festzuhalten, gerade einen Perspektivwechsel ermöglichen?”[7] To say maybe equals to establish a critical attitude, to open possibilities for discussion and change. The play I have just watched is a repetition of the same scenario subjected to variables. Brecht’s Jasager/Neinsager are clearly the model, providing both a parable-like narrative and the concept of subjecting the same scenario to variations. Eisenach’s Die Vielleichtsager, however, adds an element of resolution to the process of repetition and exploration of variables. The third scenario is presented as the one where the learning process is complete: the three characters learn to say maybe and ponder the variable of a situation of social conflict. They can get rid of the ritualistic garments and conclude the role-play. The previous scenarios, where consent to social violence was either given or refused, were functional to inform the final variation.

There are two narrative evolutions that can be distinguished in the play. The first is a circular one where each third of the performance is an alternative scenario. The other is linear and outlines a dialectical process in the Hegelian/Marxist sense: Thesis (Scenario 1, saying YES to the social norm); Antithesis (Scenario 2, saying NO to the social norm); Synthesis (Scenario 3, saying MAYBE to the social norm). Elements in the performance underline these two simultaneous processes. Each time a different performer sings the prologue of the Jasager, a different emotional landscape frames the uttering of Brecht’s lines, and a different embodied presence presents and filters the dilemma of consent and disagreement with social rules. The three musical performances are put at the same level in the sense that they are simply different interpretations of the same material. They establish a non-linear progression between the three scenarios by explicating circumstantial differences. Comical gags serve a similar function as they seem to emerge from circumstantial elements of each scenario. Finding the gun, which is always introduced by a percussion beat, is a good example. In the first and third scenario, it offers a reason for comical relief: in the first because Moltzen seems not to be aware and almost scared of having it in his possession, although his lines suggest that he is conscious of bearing a weapon; in the last because Epply appears to be happy to have a weapon with which to threaten Moltzen. On the other hand, a sense of linear continuation is given by the scene’s transformation, with the gradual removal of the curtains in association with the story’s repetition. As each section of the piece is concluded, the bare structure of the stage is easier to see, and the man hunted by the giant skeleton becomes a less prominent element. During the third repetition, the image from Kuniyoshi’s woodblock print is not visible at all. In the end, the performers give up their costumes in the act of saying maybe: the parable can be concluded on the third attempt when there is an act of sublation, of learning from variations and possibilities and of development of a new consciousness. The anarchy of subjective, casual, and circumstantial differences among scenarios is brought back to a clear and precise message in the act of saying maybe as an attitude towards participation in the collective.

Die Vielleichtsager is, arguably, not a Lehrstück. The process of exploration of social reality was at no point meant to actively involve all the people present in the auditorium, and a clear division between spectators as meaning-receivers and performers as meaning-makers was established. Whereas it has been argued that a Learning Play does not necessarily have to be a participatory performance,[8] the engagement with the dialectical process was kept on the level of something that spectators have no active role in processing but are simply shown. To put it in simpler terms, Brecht wrote the Jasager and eventually the Neinsager not to enforce a dichotomy but to allow for the exploration of options: not to point to a new form of subjectivity but to point at how a new subjectivity can be constituted. It should be clarified that the production was advertised as a piece inspired by Brecht’s Jasager/Neinsager, not as an attempt to develop a new Lehrstück. Furthermore, the very idea of the Lehrstück is arguably not fixed, and so it can be subjected to interpretation to a considerable extent. However, a certain degree of emphasis was applied in relating the piece to Brecht’s original work – testified to by the explicit references to Brecht’s Learning Plays both in the advertisement material and in the performance programme. Given the institutional identity of the Berliner Ensemble as both a mainstream cultural venue and as Bertolt Brecht’s theatre, it is worth raising a few points about the way a piece hosted and produced by this venue was inspired by the Brechtian concept of Große Pädagogik and how this concept was presented to the lay public.

It is my belief that a Lehrstück took place during the making of Die Vielleichtsager, although not on the stage for the audience to experience. What I mean is that Alexander Eisenach’s process of reading, appreciating, rewriting, and remaking on the stage Brecht’s material was the real Lehrstück. Eisenach’s play shows a deep engagement with Brecht’s Jasager, from the quoting of lines and narrative elements to the employment of a certain aesthetic orientalism to create an estranging effect. Of the three variations written by Eisenach, the first is meant to map the Jasager onto a contemporary narrative. The conflict between collective and individual good is transported in a realistic scenario where a scholar and his students can replace the teacher and the young pupils, and a scientific expedition can replace the journey to fetch medicine. Social participation is tied to the question of science, research practice, and its role in modern society. The other two variations are placed in contexts that we could frame as scientific fiction: the colonisation of Mars and the discovery of other species with the same cognitive and intellectual capacities as humans.[9] In both cases, the contention relies on the way scientific knowledge implies ties with social responsibility and of what the collective requires from those who are “nicht einverständen mit dem Falschen.” In the second scenario, the refusal of collective rule implies the refusal of the decision to abandon planet earth, which the group had agreed upon, instead of trying to mend human-induced damage. In the other, the refusal concerns, at least in the beginning, a self-preservation instinct: one of the crew members is afraid of the octopi. Eisenach’s text is interesting in the way he maps onto the Jasager elements of contemporary discussions on science and societal development, as well as tropes from scientific fiction and pop culture that feed into the ethical debate on science. Die Vielleichtsager, on a dramaturgical level, also provides an interesting juxtaposition between the individual body and collective norm. The challenge to collective expectation always comes from an uncontrolled function of the body. This could be illness, an emotional bewilderment triggered by seeing earth from space, or fear. In this sense, the making of the play could be a Lehrstück-process understood as a process of confrontation and experimentation with ideas in connection to an individual experience such as considering the function of science in modern society. The development of the musical score and of the scenography may be part of this process as well, at least at the level of pondering and reworking some aesthetic elements from the original Jasager (music as a way of establishing attitudes towards action; orientalism).[10]

However, the performance event in which I took part as a spectator was not a Lehrstück. At least in the way Brecht conceived of them, the Jasager does not invite us to say Yes, and the Neinsager does not invite us to say No. But the Vielleichtsager does invite us to say Maybe. The purpose of Brecht’s original experiments (regardless of how successful they may have been) was to stimulate critical thought on how to develop attitudes in response to conflictual aspects of social participation and to socially normalised violence. The Lehrstücke were an exercise in dialectical thought insofar as they helped to interiorise the process of dialectical thought itself, not to make people reach given conclusions.[11] What I saw on the Neues Haus stage was a parable-piece: a dialectical parable but a parable. The performance itself was engaging, and the ideas proposed would correspond to what I would call a critical perspective. But the social function of a production like this still falls within the terms of traditional dramatic theatre. It is a piece aimed at providing a message, which it delivers quiet effectively. However, the engagement with the nature of ideology in neoliberalism – a point rather emphasised in the presentation of the piece – can be questioned to an extent. Can market ideology[12] be questioned by providing a message about the necessity to be critical thinkers? This may be effective for some, maybe many. But at the same time, one has to reckon that even the act of partaking in cultural initiatives is in itself a field of human experience where the market dynamic of return-on-investment can be applied. Is it possible that the act of spending free time watching a piece of theatre is a form of adherence to ideology? Is it possible that saying maybe is a luxury not everyone can afford given the forms of social conflicts experienced by different groups and individuals? This is a contentious statement. As Alexander Eisenach proposes, we could answer with a maybe and we would probably be right in doing so. However, the way this production was realised and sponsored by an institution that has a strong historical association to Brecht’s legacy may highlight some relevant points to discuss in regard to any endeavour to work with and through the concept of Lehrstück.

The Berliner Ensemble has sponsored a production that revisits the concept of Lehrstück without considering many of the most challenging and potentially progressive elements of the practice: the training in a transformative model of thinking instead of the presentation of behavioural models; the opening of theatre to communities that do not access institutionalised culture (an opening move that in principle can be enacted by institutions as well); the exploration of processes of collective critical thinking and creative making. As I stated above, a Lehrstück took place. And it was functional to the development process of a theatre production. That the Learning Play can be understood as a dispositive is not a new opinion.[13] And a dispositive is, by definition, subjected to modalities of application. The Lehrstück can be a tool for theatre making available to artists who operate within the terms of traditional theatre. These artists may operate within the terms of ideological consensus or employ traditional theatre as a site of experimentation and activism (This depends on individual cases). At the same time, it is a dispositive for those who wish to take on the challenge of constituting a new social function for theatre as Brecht envisaged it. The Learning Play is a tool for the embodiment of dialectical thought. Like all tools, its employment depends as much on what it is capable of doing as well as what it is used for.

[1] The production premiered on October 28, 2022, and is to remain in the Berliner Ensemble’s repertoire for 2022–2023 season.

[2] Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Triptych of Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, Woodblock print, c. 1844, Honolulu Museum of Arts.

[3] Alexander Eisenach and Patrick Primavesi, ‘„Nein, Jetzt brechen wir mit dem Brauch,“’ in Die Vielleichtsager von Alexander Eisenach – Spielplan, 6.

[4] Ibid., 7.

[5] Ibid., 10-11.

[6] Ibid., 11.

[7] Quote from the Berliner Emseble’s website: “Die Vielleichtsager von Alexander Eisenach,” https://www.berliner-ensemble.de/inszenierung/die-vielleichtsager (Last accessed 22.11.2022).

[8] See for instance: Hans-Thies Lehmann and Helene Varopoulou, “Zukunft des Lehrstücks (d.h. Lernstück),“ in Brecht Gebrauchen. Theater und Lehrstück – Texte und Methoden, eds. Milena Massalongo, Florian Vaßen, and Bernd Ruping (Berlin, Milow, Strasburg: Schribi-Verlag, 2016), 410-411; Micheal Wood, “A Future for the Lehrstück? Andres Veiel and Gesina Schmidt’s Der Kick and the Recycling of Form” in The Brecht Yearbook / Das Brecht-Jahrbuch 42, eds. Tom Kuhn and David Barnett, 171-186.

[9] It should be noticed that neither scenario is something we consider entirely impossible. Efforts for the colonisation of Mars have been undertaken by billionaire Elon Musk among others; there is no evidence denying altogether the possibility of human-like intelligence in other species even if there is also no record of it (although bees and ants show very advanced capacities in this regard).

[10] I unfortunately did not have a chance to ask either the director or the performers about the production process, so this last statement should be considered as a hypothesis.

[11] See for instance: Florian Vaßen, ‘einfach zerschmeißen’: Brecht Material: Lyrik – Prosa – Theater – Lehrstück: mit einem Blick auf Heiner Müller (Berlin, Milow, Strasburg: Schibri-Verlag, 2021), 403-4.

[12] In the programme, the term “market ideology” in relation to neoliberalism is not employed. However, neoliberalism can be understood as the process of adapting any form of social interaction and any cultural activity or creative endeavour to models of market interaction, i.e., a market ideology. See: Max Haiven, Cultures of Financialization: Fictitious Capital in Popular Culture and Everyday Life (London and New York: Palgrave, 2014). Hence, I use the terms as synonyms in this context. I also appreciate that the opinions expressed by both Alexander Eisenach and Patrick Primavesi in the performance programme do not necessarily refer to the production of Die Vielleichtsager or bear direct connection to it. What should be kept in mind is that these statements were associated with the performance as part of the production realised at the Berliner Ensemble.

[13] See: Hans-Thies Lehmann and Helmut Lethen, “Ein Vorschlag zur Güte [doppelte Polariät des Lehrstücks],” in Auf Anregung Bertolt Brechts: Lehrstück Mit Schülern, Arbeitern, Theaterleuten, ed. Reiner Steinweg (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1978), 302-317.

Ernst Bloch’s The Principle of Hope, Anna Seghers, and Sigmar Polke

Caroline Rupprecht

The question of “hope” in the utopian philosophy of Ernst Bloch hinges on taking a risk. Prompted by Theodor W. Adorno to furnish “an explanation of what hope actually is”, Bloch responded: “Hope is the opposite of security. It is the opposite of naïve optimism. The category of danger is always within it” (15). It is what connects Bloch’s philosophy to the writings of Anna Seghers: having escaped the Nazis and spent 14 years in exile, Seghers returned to East Germany in the belief that, under communism, things could get better. This separates her from the younger-generation pop artist Sigmar Polke, whose family fled East Germany in 1954, and whose work in the West eventually culminated in what I identify in this essay as a form of nihilism or hopelessness.

Assuming that counter-culture in the West was informed by utopian impulses during the Sixties, I ask to what extent Bloch’s “utopian content” can still be seen in Polke’s paintings from the 1980s, whose Zeitgeist was shaped by the slogan “no future.” I begin by outlining Bloch’s process-oriented philosophy in relation to a short text by Seghers and in the second half of my essay treat a selection of Polke’s paintings. The theme of realism concerns me here in terms of how each of them uses historical referents, i.e., the degrees to which their fiction and visual art remain grounded in – or, conversely, depart from – the historical realities from which they emerged.

Bloch, in Vol.1, Part II of The Principle of Hope, in a section titled “Aporias of Realization,” describes the work of art as a “correlate” to reality: